Abstract

Background

Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA) was first described in 1882 by Brooks and was first published in 1933 by Bland, White and Garland. This rare congenital anomaly is also known as Bland-White-Garland syndrome and it occurs in 1 of 300,000 births. It is usually an isolated congenital defect but it may also present together with other congenital anomalies like atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect and coarctation of the aorta in around 5% of cases.

Case

This is a case of a 43-year old female who presented with intermittent difficulty of breathing and exertional chest heaviness and palpitations 13 years after ligation of Patent Ductus Arteriosus.

Diagnostics and therapeutics

On work-up using 2D-echocardiography, coronary CT arteriography and coronary angiography, she was discovered to have an anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from pulmonary artery. She underwent ligation of LCA from PA and CABG.

Conclusion

We should be aware of the possibility of a concomitant congenital heart disease with coronary anomalies despite its rarity. We should also maintain high index of suspicion among patients with post-tricuspid-shunt lesions prior to surgical correction as this is essential in preventing life-threatening conditions from occurring.

Setting

Philippine Heart Center, Quezon City, Philippines

Key words

anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery, ALCAPA, patent ductus arteriosus, PDA, adult type ALCAPA

Background

Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA) was first described in 1882 by Brooks [1] and was first published in 1933 by Bland, White and Garland [2]. This rare congenital anomaly is also known as Bland-White-Garland syndrome and it occurs in 1 of 300,000 births [3]. Majority (85 to 90%) of ALCAPA patients succumb to death during childhood, but for some, the collateral blood flow from right coronary artery may be sufficient to allow them to pass through childhood with relatively few minor symptoms. For the few who are able to reach adulthood, ALCAPA may be asymptomatic detected only postmortem or it may present as difficulty of breathing, chest heaviness or pain only during strenuous activity. It may also present as extreme as sudden cardiac death due to ischemia or malignant ventricular arrhythmias secondary to myocardial scar tissue [4]. It is usually an isolated congenital defect but it may also present together with other congenital anomalies like atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect and coarctation of the aorta in around 5% of cases [5].

Locally, only three publications regarding this anomaly are available [6-8]. The reports involved three pediatric cases and only one young adult. This case reports a 43-year old female who presented with chest pain 13 years after ligation of Patent Ductus Arteriosus.

Case report

A 43-year old female came in our institution because of a 4-month history of sudden onset of intermittent difficulty of breathing associated with chest heaviness and palpitations on exertion. She initially consulted at a private physician where her blood pressure was noted to be elevated. She was initially given Losartan + HCTZ and Trimetazidine. This did not afford relief of her symptoms. A 2-D Echocardiography was then requested and revealed an apparently abnormal result hence she was referred to our institution. She denies smoking and illicit drug use but claims to have occasional alcoholic beverage intakes. She is a known hypertensive for 2 years, underwent patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) ligation in 2001, open cholecystectomy in 2002 and underwent D and C for an abnormal uterine bleeding in 2013. She denies any history of allergies. Family history was negative for any cardiovascular disease but was positive for malignancy. On physical examination at the outpatient department, she had stable vital signs, noted to be overweight with a BMI of 31.6 kg/m2. Her precordium was noted to be dynamic with apex beat at the 6th LICS AAL with no heaves or lifts. There was a note of grade 4/6 continuous murmur at the 3rd left parasternal border. The rest of the physical examination findings were essentially normal.

Diagnostics and therapeutics

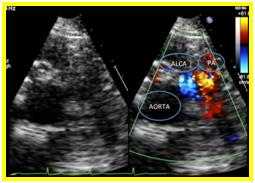

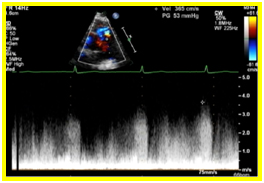

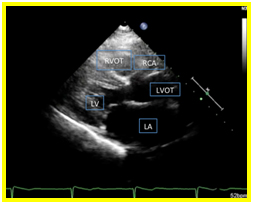

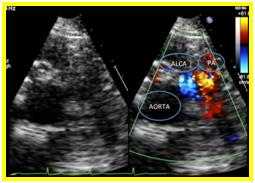

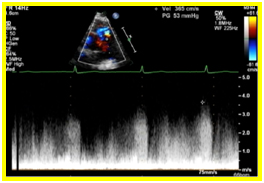

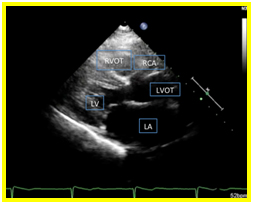

A 12 L-ECG done was noted to be normal with no signs ischemia. Transthoracic echocardiography revealed a normal left ventricular dimension with increased left ventricular mass index and increased left ventricular relative wall thickness with adequate contractility and systolic function. On parasternal short axis view, there was a note of a continuous mosaic color flow display across the aorta at the level of the left coronary artery to the pulmonary artery (Figure 1a) and a diastolic turbulent flow towards the transducer which represents the runoff from the anomalous left coronary artery. A systolic pulmonary blood flow away from the transducer and spectral doppler localization of diastolic flow disturbance going to the main pulmonary artery were also observed (Figure 1b). On parasternal long axis view, the right coronary cusp was noted to be dilated (Figure 1c). These findings were suggestive of an anomalous left coronary artery draining to the pulmonary artery.

Figure 1. 1a. Parasternal short axis view. Continuous mosaic color flow display across the aorta at the level of the left coronary artery to the pulmonary artery. 1b. Parasternal short axis view. Diastolic turbulent flow toward the transducer which represents the runoff from the anomalous left coronary artery. A systolic pulmonary blood flow away from the transducer and spectral doppler localization of diastolic flow disturbance going to the main pulmonary artery were also observed 1c. On parasternal long axis view, the right coronary cusp was noted to be dilated

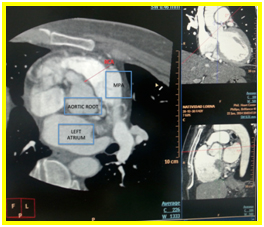

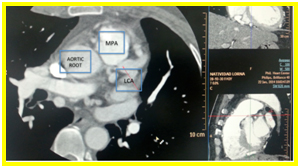

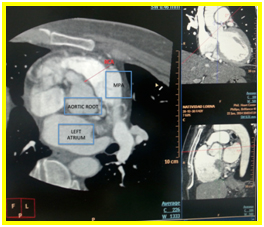

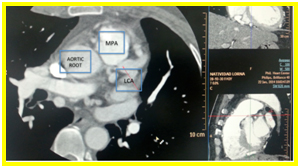

Coronary CT arteriography showed that the ductus is not patent. There is absence of left coronary sinus on axial view (Figure 2a) and the left main coronary artery (LMCA) appears to be originating anomalously from the main pulmonary artery and it bifurcates into left anterior descending artery (LAD) and left circumflex artery (LCx) also seen on axial view (Figure 2b).

Figure 2a. Axial view. Absence of left coronary sinus

Figure 2b. Axial view. Left main coronary artery (LMCA) appears to be originating anomalously from the main pulmonary artery and it bifurcates into left anterior descending artery (LAD) and left circumflex artery (LCx)

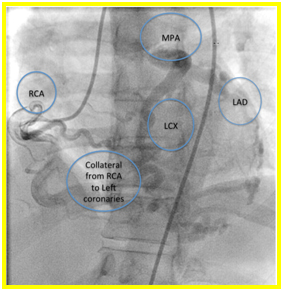

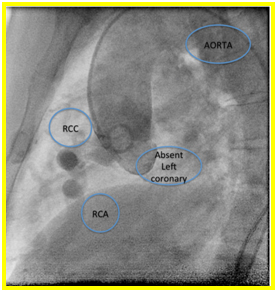

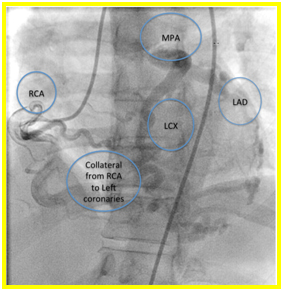

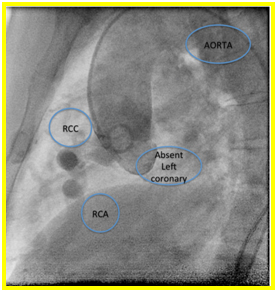

Suspicion of ALCAPA was proven with coronary angiography. Extensive collaterals were noted from the right coronary artery to the left coronary system (Figures 3a and b). Patient underwent ligation of left coronary artery from main pulmonary artery and Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) using Left Internal Mammary Artery (LIMA) to LAD. Patient tolerated the procedure and was discharged stable after 1 week. Currently she is asymptomatic and is being maintained on Enalapril 5mg tab once a day.

Figure 3a and 3b. On right coronary artery cannulation and injection showing Anomalous origin of left coronary artery from pulmonary artery with extensive collaterals from right coronary artery to the left coronary system.

Discussion

When ALCAPA is present in an individual, it is well tolerated during fetal and early neonatal life because pulmonary arterial pressure is the same as the systemic pressure. This leads to an antegrade flow in both the anomalous LCA and the normal right coronary artery [9]. When the pulmonary vascular resistance and pulmonary arterial pressure decrease shortly after birth, antegrade flow also decreases together with the oxygen content of the anomalous left coronary artery. To compensate, collateral circulation between the right and left coronary systems follows. This causes coronary steal phenomenon wherein there is a reverse in the flow of left coronary artery to the pulmonary trunk due to low pulmonary arterial pressures. This preferential blood flow into the low-pressure pulmonary circulation rather than into the high-resistance myocardial circulation will eventually leads to myocardial ischemia [4].

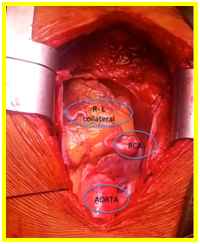

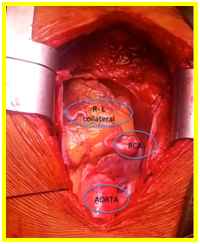

Depending on the rate of fall of pulmonary artery pressure and the development of collateral connections with the right coronary artery, the age of onset of symptoms varies [4,9]. Eighty to ninety percent of infants born with ALCAPA will not survive the first year of life [9]. In the remaining 10-20%, factors that enable survival to adulthood include abundant interarterial collateral vessels between right coronary artery (RCA) and the LCA, RCA dominance, minimal coronary steal from the pulmonary artery and development of systemic blood supply to the LCA [4]. For those who survive, the left ventricle will gradually improve over a period of 4–6 weeks while collaterals develop. A concomitant congenital shunt in post-tricuspid area may be protective in this case as it deters the fall in the pulmonary artery pressure and at the same time maintains supply of oxygenated blood to the left coronary artery system. This prevents the dramatic changes seen in a child with an isolated ALCAPA [10]. In our patient, the occurrence of intermittent difficulty of breathing and chest pain during exertion years after her PDA ligation, despite a normal resting 12-L ECG and a preserved LV function on 2D-echocardiography is an indication of a beginning left ventricular subendocardial perfusion compromise. Despite the extensive collaterals from RCA to the left coronary system developed in our patient seen intraoperative (Figure 4) and observed during the physical examination (grade 4/6 continuous murmur at the 3rd left parasternal border), sufficient coronary perfusion was not achieved when the patient is engaged in strenuous physical activities. This is due to low-pressure coronary perfusion with poorly oxygenated blood and from the coronary steal from the pulmonary circulation and reversed flow in the left coronary vessels to the pulmonary artery. The previously present congenital post-tricuspid shunt, a PDA in this case, prevented fall in pulmonary artery pressure, and together with the extensive collaterals maintained adequate antegrade delivery of oxygenated blood to the LMCA. When our patient underwent PDA ligation, subsequent pressure changes in the coronary circulation happened creating a lower-pressure coronary perfusion and a retrograde flow in the left coronary vessels to pulmonary artery. This was not enough to supply the whole myocardium, despite the collaterals especially on strenuous physical activities, as seen in our patient. Mapping of the coronaries could have prevented the occurrence of symptoms in our patient.

Figure 4. Extensive collateral developed from right coronary artery to the left coronary system

Conclusion

From this case, we can learn that we should be aware of the possibility of a concomitant congenital heart disease with coronary anomalies, in particular PDA with ALCAPA, despite its rarity. We should also maintain high index of suspicion among patients with post-tricuspid-shunt lesions prior to surgical correction as this is essential preventing life-threatening conditions from occurring.

2021 Copyright OAT. All rights reserv

References

- Brooks H (1882) Two cases of an abnormal coronary artery of the heart arising from the pulmonary artery: with some remarks upon the effects of this anomaly in producing cirsoid dilation of the vessel. J Anat 20: 26–29.

- Bland EF, White PD, Garland J (1933) Congenital anomalies of coronary arteries. Report of unusual case associated with cardiac hypertrophy. Am Heart J 8: 787– 801.

- Dodge-Khatami A, Mavroudis C, Backer CL (2002) Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery: collective review of surgical therapy. Ann Thorac Surg 74: 946–955.

- Peña E, Nguyen ET, Merchant N, Dennie C (2009) ALCAPA syndrome: not just a pediatric disease. Radiographics 29: 553-565. [Crossref]

- Takimura CK, Nakamoto A, Hotta VT, Campos MF, Malamo M, et al. (2002) Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery: report of an adult case. Arq Bras Cardiol 78: 309-314. [Crossref]

- Sison MC, Del Rosario JD, Sison ED (2005) Extreme presentations of anomalous left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA): a wheezy infant and an asymptomatic adolescent. Acta Medica Philippina 39: 51-54.

- Dancel-San Juan BR (2009) Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery arising from the pulmonary artery: Myocardial perfusion scintigraphy findings. Phil Heart Center J 15: 85-89.

- Martinez MD, Villanueva Z, Rico A. Anomalous connection of the left coronary artery to pulmonary artery (ALCAPA) in a 25-year old female s/p atrial septal defect closure and patent ductus arteriosus ligation. Philippine Heart Center, Case Report.

- Perloff JK and Marelli AJ. Perloff’s Clinical Recognition of Congenital Heart Disease. Elsevier Saunders. 6th Edition: 394-403

- Awasthy N, Marwah A, Sharma R, Dalvi B (2010) Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery with patent ductus arteriosus: a must to recognize entity. Eur J Echocardiogr 11: E31. [Crossref]