Abstract

Background

Malignant central nervous system germ cell tumours are subdivided intogerminomas and malignant nongerminomatous germ cell tumours. Germinomas are exquisitely radio- and chemosensitive,whereas nongerminomatous germ cell tumoursare less so.

Case report

We discuss a 13-year-old Caucasian girl, who presented with an acute exacerbation of an eating disorder diagnosed 3 years prior to thecurrent consultation. Diabetes insipidus, growth arrest during the preceding 2 years and absent pubertal development were diagnosed.Endocrinologicalevaluation confirmed panhypopituitarism. Following brain magnetic resonance imaging,a subtotal resection of an enhancing mass in the sellar/suprasellar region was performed. Histology revealeda mixed nongerminomatous germ cell tumour. β-human chorionic gonadotropin was increased in cerebrospinal fluid and serum.

Conclusion

We hypothesize that the diagnostic delay of 3 years in this patient may have resulted in transformation from a pure germinoma into a nongerminomatous germ cell tumour.This highlights the need for a change in the clinical diagnostic approach,with the emphasis on early diagnosis.

Key words

diagnostic delay, germinoma, malignant transformation, nongerminomatous germ cell tumour

Abbreviations

AFP: α-Fetoprotein; β-HCG: β-human Chorionic Gonadotropin; CSF: Cerebrospinal Fluid; EFS: Event-free Survival;MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; NGGCT: Nongerminomatous Germ Cell Tumours

Introduction

Malignant central nervous system germ cell tumours can be divided into two major categories: germinomas and malignant nongerminomatous germ cell tumours (NGGCT). NGGCTs can be further classified into teratomas and malignant germ cell tumours,including choriocarcinoma and yolk sac tumour, which produce β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG) and α-fetoprotein (AFP), respectivelyand embryonal carcinoma. Mixed NGGCTs with components of different histological subtypes are common [1,2].

Germinomas are exquisitely radiosensitive with 5-year event-free survival (EFS)>90% [2,3]. The dose and volume of radiation therapy can be reduced by adjuvant chemotherapy[4,5], which in turn is associated with fewer neuroendocrinological sequelae.

Malignant NGGCTsare associated with a poorer prognosis and require chemotherapy as well as craniospinal irradiation. Their5-year EFSranges from10% (choriocarcinoma or embryonal carcinoma) to 70% (mixed NGGCT) [2,6].

Case presentation

A 13-year-old Caucasian girl presented with an acute exacerbation of an eating disorder, which had been diagnosed 3 years earlier. She had beenundergoing psychologicalcounsellingsince the diagnosis was made and had been hospitalized2 years prior to presentation with a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa, nonself-induced vomiting and psychogenic polydipsia. Serum potassium and sodiumwere within normal rangeand an abbreviated non-standardized fluid deprivation test was reportedto be normal.

Currently shepresented withhypernatriaemic dehydration,which was not responsive to intravenousrehydration. Diabetes insipidus was diagnosed following a pathological fluid deprivation test.

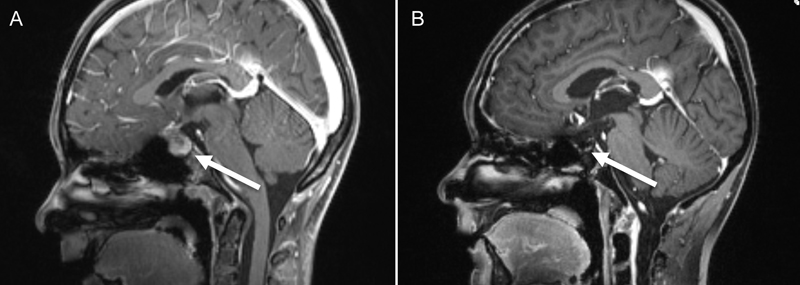

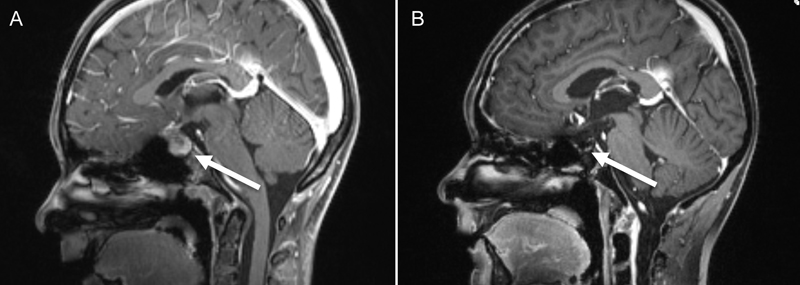

Growth arrest during the previous 2 years and absent pubertal development were detected.Endocrinologicalevaluation confirmed the diagnosis ofpanhypopituitarism. The patient was substituted with desmopressin, hydrocortisone and levothyroxine. She also had decreased visual acuity resulting from optic nerve neuropathy caused by chiasmic compression. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a homogeneously enhancing mass in the sellar/suprasellar region(Figure 1A). Macroadenoma, craniopharyngeomaand Langerhans cell histiocytosis were considered in the differential diagnosis and transsphenoidal subtotal resection was performed. Neuropathological examinationrevealed an NGGCT, specifically a mixed malignant germ cell tumour involving germinoma and choriocarcinoma.

Figure 1. Contrast enhanced MRI(A) at diagnosis and (B) the follow-up MRI at the end of therapy

The diagnosis was made according to the criteria stipulated by the current World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumours of the central nervous system [7].

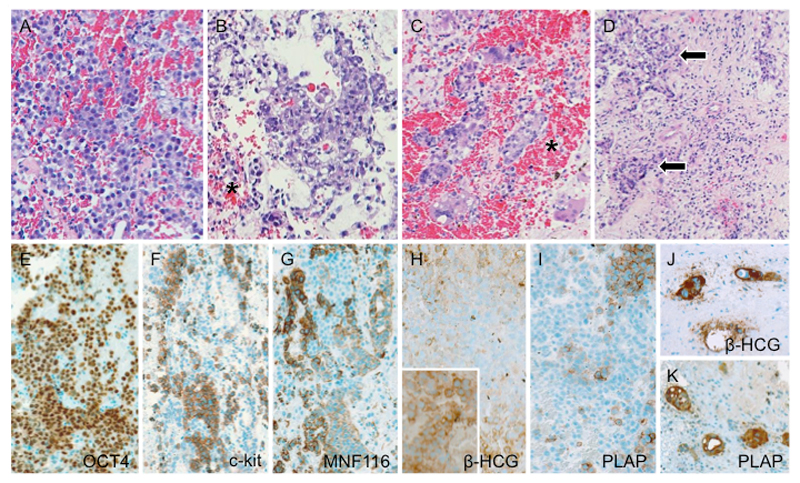

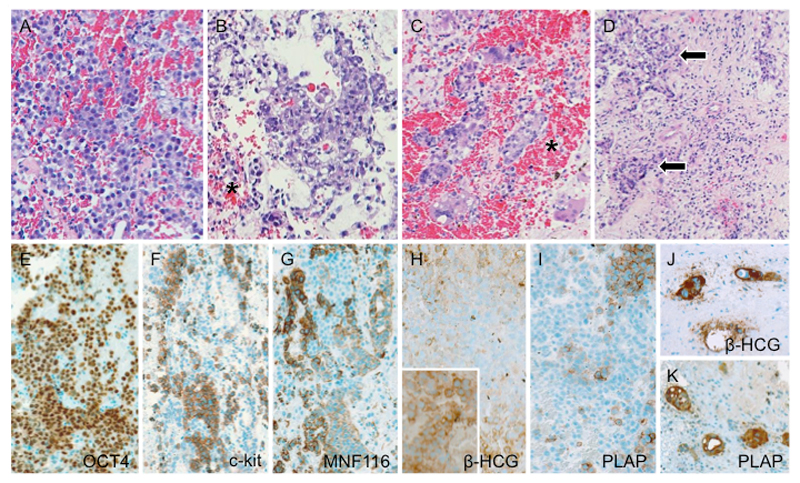

Light microscopy indicatedthat the tumourwas neither of pituitary-epithelial nor ofglial origin. A highly malignant biphasic germ cell neoplasm with an undifferentiated dysgerminoma-like texture, punctuated by emergent foci of epithelial and syncytiotrophoblastic differentiation (Figures 2A-K) was diagnosed. No teratomatous elements were identified. β-HCG was increased in both cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum (686.2U/l and 489U/l respectively). In the CSF no circulating cells were detected. Metastases were excluded by spinal MRI and abdominal ultrasound.

Figure 2. Histology and immunophenotype of mixed malignant germ cell tumour. (A) The prevailing component consists of solid sheets of medium-sized, undifferentiated cells with slightly basophilic to clear cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei, corresponding in their majority to germinoma. (B) In between, foci of choriocarcinomatous differentiation exhibiting overtly epithelial qualities as well as (C)syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells are identified. Note ubiquitous presence of intratumoural hemorrhages (asterisks) along with (D) granulomatous inflammatory reaction (arrows) – both characteristic of malignant germ cell neoplasia. (E) There is generalized immunoreactivity for OCT4. Conversely, labeling for (F) c-kit and (G) cytokeratin tend to be mutually exclusive; the former being detected in the germinoma moiety, whereas the latter associates with epithelial phenotype in the choriocarcinoma component. (H) While human chorionic gonadotrophin β chain and (I) placental alkaline phosphatase tend to yield faint to negative staining in the germinoma, groups of morphologically similar cytotrophoblastictumour cells display intense immunoreactivity (inset in H), as also do syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells (J, K).

Photomicrographs not labeled otherwise depict slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The immunoreactions have been visualized with polymer-bound horseradish peroxidase (Envision+; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and 3,3‘diaminobenzidine as chromogen. Original magnification: (A,B,D) x150; (C, J,K) x200; (E – I) x125.

Multimodal therapy according to COG protocol ACNS0122[8]including 6 cycles of chemotherapy (carboplatin, etoposide and ifosfamide) was started. Second-look surgery after the 6 cycles were completedshowed only scar tissue. Craniospinal irradiation with 36 Gray and a local boost up to 54 Graywasadministeredwithout prior high dose chemotherapy.The patient showed complete remission at the end of therapy, confirmed by MRI (Figure 1B) and a normal β-HCGlevel inserum and CSF.

Discussion

We hypothesize that the diagnostic delay of 3 years in this patient may have resulted in transformation of a pure germinoma into an NGGCT witha poorer prognosis. This hypothesis is supported by boththe so-called germ cell theory and several case reports.

The germ cell theoryoriginally developed by Teilum[9,10]proposes thatgerm cells give rise to germinomas and to tumours composed of totipotent cells. These cells can develop into embryonal carcinomas, from which endodermal sinus tumours (yolk sac tumours), choriocarcinomas, and teratomasarise.

We are aware of 5 patients reported in the literaturewith an initial diagnosis of germinoma and relapse diagnosis of NGGCT(Table 1). Four of them had undergone radiationor chemotherapy before the diagnosis of NGGCT was made.

2021 Copyright OAT. All rights reserv

Konet al.described a 19-year-old man with a pure germinoma in the pineal region,who was successfully treated with chemotherapy followed by local irradiation. Eight months later ventricular wall dissemination was detected by MRI andCSF was positive for β-HCG and malignant cells. Craniospinal irradiation was performedand the CSF cytology became negative. Two months later MRI showed tumour recurrence. As gamma knife radiosurgery was unsuccessful, a total resection was performed. Histological examination showed an immature teratoma. Despite additional chemotherapy, the tumour reappearedat the trigone of the left lateral ventricle. Tumourextirpation was performed and an embryonal carcinoma was diagnosed on histology[11].

Kamitaniet al.described a 15-year-old boy with a neurohypophyseal pure germinoma, which was treated by subtotal resection and radiochemotherapy. Transformation to a mixed NGGCT consisting of components of germinoma, choriocarcinoma, immature teratoma and an undifferentiated sarcomatous componentwas diagnosed following relapse[12].

Takahashi et al.described athird patient, 22-year-old man,with suprasellar germinomadiagnosed on biopsy. He underwent chemotherapy with carboplatin and etoposide followed by craniospinal irradiation. Three years after completion of treatment, an AFP-secreting testicular NGGCT was found[13].

Lastly,Takeuchi et al.described a 17-year-old man diagnosed with a pure germinoma in the pineal and suprasellar region. After subtotalresection, the patient underwent chemo- and radiotherapy and the mass disappeared. Five years later achoriocarcinomain the left lateral ventricle wasdiagnosed following subtotal resection[14].

There are two possible explanations for the sequence germinoma – NGGCT in these four patients. First, diagnosis of germinomamay have been due toa sampling errorof a malignant lesion that was predominantly, but not purely germinomaand therapy may then have selected for more malignant clones. Secondly, tumourcells may have undergone transformation due to therapy-inducedchanges in their genomic structure.

Based on a fifth published case and our patient, we hypothesize that throughdelay in diagnosis and/or treatment, a spontaneoustransformation from germinoma to NGGCT is alsopossible.Wong et al.described a young girl with transformation of a germinoma into an NGGCT prior to initiation of chemo- and radiotherapy. The patient presented with primary diabetes insipidusat the age of ten years. Three years latershe was diagnosed with a germinoma based on a biopsy and negative serum and CSF markers. Six weeks after histological diagnosisand prior to initiation of planned therapy, serum and CSF marker analysis revealed marked elevation of AFP, indicating transformation of the germinoma into an NGGCT[15].

Theoretically the initial diagnosis could have been incorrect due toa sampling problem, but serum and CSF samples were repeatedlynegative for AFP and β-HCG. She was also monitored by MRI for three yearsand the initially mildly thickened infundibulum showed an increase in size, leading to biopsy. At that time AFP and β-HCG were still negative.

Conclusions

Germ cell tumours should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of eating disorders and delayed puberty.Should the hypothesis that germinomas can spontaneously transform into NGGCTswith a poorer prognosis be correct, early diagnosis is crucial.

Alternatively, amixed GCT may have been misdiagnosed initially as a pure GCT and the secretory component became predominant over time or the tumourshowed an indolent evolution. Patients with suprasellar GCTs often have chronic subtle symptoms, and their tumours are diagnosed incidentally on imaging studies performed for unrelated reasons. Delays in diagnosis are common and symptoms related to endocrinopathyare associated with delays of greater than 12 months and a higher incidence of disseminated disease [16].

In our patientgrowth arrest might have been an early symptom of a tumourin the hypothalamic-pituitary-axis [17]and a crucial sign of pituitary hormone deficiencies, as patients with severe anorexia nervosa do continue to grow[18],the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa should not be made without prior CNS imaging[19].

It is known thatendocrinologicalsymptoms may be present years before a massbecomes visible on MRI[20,21]. In patients with idiopathic diabetes insipidus or other symptoms of hypopituitarism,MRI and monitoring of tumour markers (AFP and β-HCG in serum and CSF) as well as tests of anterior and posterior pituitary function should be performed at regular intervals[22].

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Jane McDougall and Amber Hjelm who revised the manuscript regarding English language.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Fujimaki T(2009) Central nervous system germ cell tumors: classification, clinical features, and treatment with a historical overview. J Child Neurol24:1439-1445. [Crossref]

- Echevarría ME, Fangusaro J, Goldman S (2008) Pediatric central nervous system germ cell tumors: a review. Oncologist13: 690-699.[Crossref]

- Kawabata Y, Takahashi JA, Arakawa Y, Shirahata M, Hashimoto N (2008) Long term outcomes in patients with intracranial germinomas: a single institution experience of irradiation with or without chemotherapy. J Neurooncol88: 161-167.[Crossref]

- Allen JC, Kim JH, Packer RJ(1985)Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for newly diagnosed germ-cell tumoursof the central nervous system. J Neurooncol3:147-152. [Crossref]

- Sawamura Y, Shirato H, Ikeda J, Tada M, Ishii N, et al. (1998) Induction chemotherapy followed by reduced-volume radiation therapy for newly diagnosed central nervous systemgerminoma. J Neurosurg88:66-72. [Crossref]

- Poplack DG, Pizzo PA(2010) Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology, (6thedn), Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Rosenblum MK, Nakazato Y, Matsutani M (2007) Germ Cell Tumors. In: Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK (Eds). WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System, IARC, Lyon: 197-204.

- NCT00047320 cg.

- Teilum G (1965) Classification of endodermal sinus tumour (mesoblatomavitellinum) and so-called "embryonal carcinoma" of the ovary. ActaPatholMicrobiolScand 64: 407-429.[Crossref]

- Teilum G (1958) Classification of testicular and ovarian androblastoma and Sertoli cell tumors; a survey of comparative studies with consideration of histogenesis, endocrinology, and embryological theories. Cancer11: 769-782.[Crossref]

- Kon H, Kumabe T, JokuraH, Shirane R(2002)Recurrent intracranial germinoma outside the initial radiation field with progressive malignant transformation. ActaNeurochir144:611-616. [Crossref]

- Kamitani H, Miyata H, Ishibashi M, Kurosaki M, Mizushima M, et al. (2006) Mixed germ cell tumors with abundant sarcomatous component in the temporal lobe after radiochemotherapy of neurohypophysealgerminoma: a case report. Brain Tumor Pathol23:83-89. [Crossref]

- Takahashi S, Yoshida K, Mikami S, Oya M, Kawase T(2008) Development of testicular alpha-fetoprotein-secreting germ cell tumor 3 years after treatment of intracranial lesion identified as non-secreting germ cell tumor on the basis of clinical data case report. Neurol Med Chir48:522-525. [Crossref]

- Takeuchi S, Takasato Y, Masaoka H, Hayakawa T, Otani N, et al. (2009) Malignant transformation of an intracranial germinoma into a choriocarcinoma. BMJ Case Rep2009.[Crossref]

- Wong JM, Chi SN, Marcus KJ, Levine BS, Ullrich NJ, et al. (2010) Germinoma with malignant transformation to nongerminomatous germ cell tumor. J NeurosurgPediatr6: 295-298.[Crossref]

- Sethi RV, Marino R, Niemierko A, Tarbell NJ, Yock TI, et al. (2013) Delayed diagnosis in children with intracranial germ cell tumors. J Pediatr163: 1448-1453.[Crossref]

- Gottschling S, Graf N, Meyer S, Reinhard H, Krenn T, et al. (2006) Intracranial germinoma: a rare but important differential diagnosis in children with growth retardation. ActaPaediatr95: 302-305.[Crossref]

- Pfeiffer RJ, Lucas AR, Ilstrup DM (1986) Effect of anorexia nervosa on linear growth. ClinPediatr (Phila)25: 7-12.[Crossref]

- Hensgens TB, Bloemer E, Schouten-van Meeteren AY, Zwaan CM, Van den Bos C,et al. (2013) Psychiatric symptoms causing delay in diagnosing childhood cancer: two case reports and literature review. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry22: 443-50.[Crossref]

- Lin IJ, Shu SG, Chu HY, Chi CS (1997) Primary intracranial germ-cell tumor in children. Zhonghua Yi XueZaZhi (Taipei) 60: 259-264.[Crossref]

- Dodek AB, Sadeghi-Nejad A (1998) Pineal germinoma presenting as central diabetes insipidus. ClinPediatr (Phila) 37: 693-695.[Crossref]

- Jorsal T, Rørth M (2012) Intracranial germ cell tumours. A review with special reference to endocrine manifestations. ActaOncol51: 3-9.[Crossref]