Abstract

In recent years, it has been proposed by different recent research studies that closure of superficial layer of laparotomy wound a monofilament suture is better than using a polyfilament in terms of postoperative analgesic outcomes and surgical site infection rates, types, sites, grades, severity, and switch abscess formation. So, quite reasonably this study was aimed at to assess that in our clinical setup. In this Randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT), surgical site infection rates were found as 17.3% and 24.7% in Experimental group (Group A: Closure of superficial layer of laparotomy was done with Monofilament- Polydioxanon Suture) and in Control group (Group B: Closure of superficial layer of laparotomy was done with Polyfilament- Polyglactin Suture) sequentially. Among the 26 patients of surgical site infections, 12 patients (08%) had superficial infections followed by 09 patients (06%) had deep infections in Experimental group. In case of Control group, these rates were 14% and 6.7% respectively. In this RCT, the average pain and tenderness in postoperative period in both groups were assessed by using the pain and tenderness score respectively. In Group A, approximately on day 03 and onwards, the average pain score fall below 01, but in group B, the approximate length of it was 5 days after surgery. On the other hand, the average tenderness score was found to decline below 01 on 4th postoperative day in both groups. A gradual fall of average pain was observed from 1st to 5th postoperative day in both groups and at the end of day 5, the average pain score was found below 01. No significant variation of this falling trend was detected in between the both study groups, therefore, the difference of outcomes of average pain and tenderness can be said to be minimal in contrast to the results of both groups. In a nutshell, there was no significant difference in the post-surgical analgesic outcomes in terms of postoperative average pain and tenderness in both groups, although comparatively better post-surgical analgesic outcomes were observed in Group A.

Key words

post-operative analgesic outcomes, surgical site infection, emergency laparotomy, monofilament, polyfilament

Introduction

In this modern era it is well established that surgical site infection has close relation with the choice of suture materials. Different types of suture materials are used for closure of abdominal incisions. There has been continuous debate on results of monofilament with polyfilament suture materials. As stated earlier according to the “Guideline for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 1999” presented by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s: “Surgical site infection is infection at the site of surgical procedure within 30 days of operation but may be within one year if prosthetic or implant surgery is performed [1,2]. The US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) definition insists on a 30-day follow-up period for non-prosthetic surgery and 1 year after implanted hip and knee surgery [1,2].

Sources of infection may be Primary: acquired from a community or endogenous source (such as that following a perforated peptic ulcer) or secondary or exogenous (Health care associated infection): acquired from the operating theatre (such as inadequate air filtration) or the ward (e.g. poor hand-washing compliance) or from contamination at or after surgery (such as an anastomotic leak). Secondary or Health care associated infections include Respiratory infection (ventilator associated pneumonia), urinary tract infections (urinary catheter associated infection), bacteraemia (associated with vascular catheter) and surgical site infections [1-4].

Surgical site infections are classified into superficial surgical site infection (When infection involves skin and subcutaneous tissue of the incision within 30 days of operation), deep surgical site infection (infection in the deeper Musculo-fascial layers) and organ space infection (such as an abdominal abscess after an anastomotic leak) [1,5,6]. Currently, in the United States alone, an estimated 27 million surgical procedures are performed each year [2]. The CDC’s National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) system, established in 1970, monitors reported trends in nosocomial infections in U.S. acute-care hospitals. Based on NNIS system reports, SSIs are the third most frequently reported nosocomial infection, accounting for 14% to 16% of all nosocomial infections among hospitalized patients [7].

In 1980, Cruse estimated that an SSI increased a patient’s hospital stay by approximately 10 days and cost an additional $2,000. A 1992 analysis showed that each SSI resulted in 7.3 additional postoperative hospital days, adding $3,152 in extra charges. Other studies corroborate that increased length of hospital stay and cost are associated with SSIs. Deep SSIs involving organs or spaces, as compared to SSIs confined to the incision, are associated with even greater increases in hospital stays and costs [8,9].

Quantitatively, it has been shown that if a surgical site is contaminated with >105 microorganisms per gram of tissue, the risk of SSI is markedly increased [1]. However, the dose of contaminating microorganisms required to produce infection may be much lower when foreign material is present at the site (i.e., 100 staphylococci per gram of tissue introduced on silk sutures) [1]. If there is a silk suture in tissue, the critical number of organisms needed to start an infection is reduced logarithmically and precipitate wound infection [10].

Although there are substantial number of randomized studies and several meta-analysis examining different techniques of abdominal fascia closure the optimal and better method of closing the abdomen has not yet been found [9,10]. Therefore the technique and material for abdominal fascia closure are still determined by local material supply and surgical traditions. Regarding optimal method of abdominal closure a variety of factors have to be considered like wound infection, wound dehiscence, incisional hernia, suture sinus, and pain [11]. Most common complication noted in this study was superficial wound infection which is the only complication found slightly more in patients of polyglycolide group. Polyglycolide is a braided, material having half-life of 20–30 days and chances of infection is more in this group of patients as harbouring organisms is more in this types of suture material than monofilament suture materials [12]. Choudhary et al. [13] demonstrated wound infection in 22.5% patients of monofilament mass closure of abdominal incisions. They found sinus formation in 2% patients of monofilament group, while in another study, it was found in 3.62% patients of monofilament group and in only 0.73% patients of polyfilament group. The meta-analysis by Hodgson et al. [14] reported less incisional hernias after closure with continuous non-absorbable sutures but also found significantly more suture sinuses and wound pain requiring further interventions.

Another clinical study demonstrated burst abdomen in 2.17% patients of prolene group and 1.47% patients of polyfilament group. In a study by Gys et al. [15] found burst abdomen in 3% patients of prolene group and 1.9% patients of polyglycolide group. Persistent pain at either end of wound was found only in monofilament group in which it was found in 8.69% patients, which may be due to the knot present at these sites [16].

On this background, the main aim of our research study was to find out the possible link between the postoperative analgesia outcomes with development of surgical site infections among the patients of contaminated surgery through emergency laparotomy and the contributing role of choice of monofilament versus polyfilament suture materials.

Methods and materials

This study was conducted as a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) with a total number of 300 indoor patients of general surgery wards (Unit 1 and 2, Ward no 9+10 and 11+12), Khulna Medical College Hospital, Bangladesh from September, 2010 to October, 2015. Among them 150 patients were in experimental group (Group A: Closure of superficial layer of laparotomy was done with Monofilament- Polydioxanon Suture) and 150 patients were in control group (Group B: Closure of superficial layer of laparotomy was done with Polyfilament- Polyglactin Suture). Simple random sampling was used to select the study population based upon the inclusion criteria. Major confounding variables such as- age, BMI, comorbidities etc. were eliminated in this RCT at a very minimal level. Almost same types of anaesthetic and peri-operative analgesic protocol were followed in all patients for post-surgical pain management.

Results

The age and sex distribution of the study population on both groups is described in Table 1.

|

Age in years

|

Male

|

%

|

Mean±SD

|

Female

|

%

|

Mean±SD

|

|

Group A (Experimental group, n1=150)

|

|

20 - 30

|

21

|

14

|

38±2.1

|

24

|

16

|

37±1.7

|

|

31 – 40

|

37

|

24.7

|

29

|

19.3

|

|

41 – 50

|

23

|

15.3

|

16

|

10.7

|

|

Total

|

81

|

54%

|

|

69

|

46%

|

|

|

|

|

Group B (Control group, n2=150)

|

|

20 - 30

|

19

|

12.7

|

36±1.8

|

16

|

10.7

|

42±1.9

|

|

31 – 40

|

41

|

27.3

|

30

|

20

|

|

41 – 50

|

17

|

11.3

|

27

|

18

|

|

Total

|

77

|

51.3

|

|

73

|

48.7

|

|

Table 1. Age and sex distribution of both groups of study population.

In this research study, the total number of patients in Group A (Experimental group, n1=150) and B (Control group, n2=150) were 150 and 150 accordingly. Table I suggests that most of the male patients in group A were in 31- 40 years age group (24.7%) followed by 41- 50 years age group (15.3%), whereas, in case of female patients, these were 19.3% and 10.7% respectively in Group A. The mean age of male patients was 38 ± 2.1 years and female patients were 42 ± 1.9 years in Group A. On the other hand, in Group B, majority of the male patients were in also 31- 40 years of age group (27.3%) followed by 20- 30 years age group (12.7%), whereas, in case of female patients, the predominant group was 31- 40 years age group (20%), followed by 41- 50 years age group (18%). The mean ages for male and female patients in Group B were 36 ± 1.8 and 42 ± 1.9 years respectively.

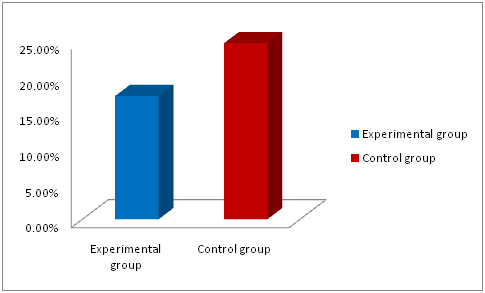

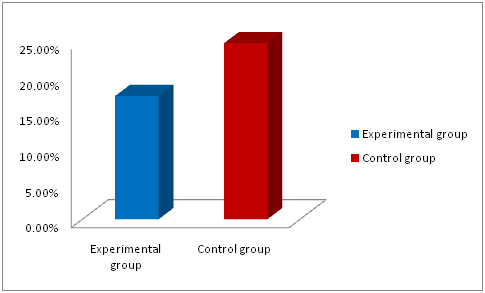

The results of this study depicts that 26 patients (17.3%) out of 150 patients in Group A developed surgical site infection, whereas, the rate was recorded as 24.7% ( 37 patients out of total 150 patients) in case of Group B (Figure 1).

Figure 1. SSI rates in both study groups.

Among the 26 patients of surgical site infections, 12 patients (08%) had superficial infections followed by 09 patients (06%) had deep infections in Experimental group. In case of Control group, these rates were 14% and 6.7% respectively (Table 2).

|

Type of SSIs

|

No. of patients

|

%

|

No. of patients

|

%

|

P value

|

|

|

Experimental group

|

Control group

|

|

|

Superficial

|

12

|

08

|

21

|

14

|

0.05

|

|

Deep

|

09

|

06

|

10

|

6.7

|

|

Organ space

|

05

|

3.3

|

06

|

04

|

|

Total

|

26

|

17.3

|

37

|

24.7

|

|

Table 2. Clinical types of surgical site infections in both groups.

In Group A, approximately on day 03, the average pain score fall below 01, but in group B, the approximate length of it was 5 days after surgery. In question of average tenderness after surgery, in both groups, it was postoperative day 04 when the tenderness was found below 01 (Table 3).

|

Group A (Experimental group, n1=150)

|

|

|

Postoperative day

|

|

|

Pain Scoring (0-4)

|

D1

|

D2

|

D3

|

D4

|

D5

|

P value

|

|

Average Pain Score

|

3 to 2

|

2 to 1

|

< 1

|

< 1

|

<1 to 0

|

> 0.1

|

|

|

|

Tenderness Scoring (0-4)

|

D1

|

D2

|

D3

|

D4

|

D5

|

P value

|

|

Average Tenderness Score

|

3 to 2

|

3 to 2

|

2 to 1

|

< 1

|

<1

|

> 0.1

|

|

|

|

Group B (Control group, n2=150)

|

|

Pain Scoring (0-4)

|

D1

|

D2

|

D3

|

D4

|

D5

|

P value

|

|

Average Pain Score

|

3 to 2

|

3 to 2

|

2- 1

|

< 1

|

<1 to 0

|

> 0.1

|

|

|

|

Tenderness Scoring (0-4)

|

D1

|

D2

|

D3

|

D4

|

D5

|

P value

|

|

Average Tenderness Score

|

3 to 2

|

3 to 2

|

2 to 1

|

< 1

|

<1

|

> 0.1

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3. Average pain and tenderness in postoperative period.

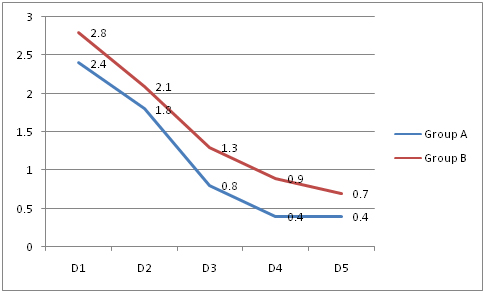

Figure 2 suggests that there was a gradual fall of pain from postoperative day 1 to 5 in both groups and at the end of day 5, the pain score was below 01 on an average.

Figure 2. Average pain score in both groups.

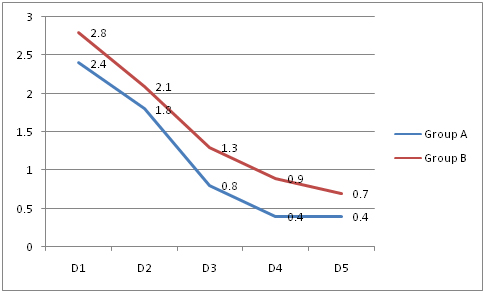

Tenderness also trended to fall gradually with the passage of time which is described in figure 3 and on 5th postoperative days, it was found less than 1 in both groups. There found no significant variation of this falling trend in between the both study groups.

Figure 3. Average tenderness score in both groups.

2021 Copyright OAT. All rights reserv

Discussion

Surgical site infection rate was the most important variable in this RCT. It was found as 17.3% and 24.7% in Experimental group and Control group sequentially. 26 patients out of 150 patients in Group A and 37 patients out of total 150 patients in group B had surgical site infection (Figure 1). It suggests that the rate of surgical site infection was significantly higher patient with polyfilament closuring of skin (and subcutaneous tissue) in contrast to monofilament closuring. Among the 26 patients of surgical site infections, 12 patients (08%) had superficial infections followed by 09 patients (06%) had deep infections in Experimental group. In case of Control group, these rates were 14% and 6.7% respectively (Table 2). So, these results here clearly and strongly suggest that polyfilament closuring is associated with higher rate of surgical site infection specially the superficial infections (Table 2).

A more or less established drawback of polyfilament suture in contrast to monofilament is stitch abscess. The results of this study suggest that the rate of switch abscess was significantly higher in patients of Group B (7.3%) in contrast to patients of Group A (2.7%) which is depicted in Figure 2.

The rates of switch abscess, burst abdomen, sinus and faecal fistula formation were found 4.7% (07 patients out of total 150), 3.3% (05 patients out of total 150) and 2.7% (04 patients out of total 150) in Group A, whereas in Group B, these were 7.3% (11 patients out of total 150), 06% (09 patients out of total 150) and 4.7% (07 patients out of total 150) respectively which is depicted in figure 4. Choudhary et al. [13] suggested sinus formation in 2% patients of monofilament group, while in another study, it was found in 3.62% patients of monofilament group and in only 0.73% patients of polyfilament group. In a particular study, a total 274 patients were finally analysed for closure of elective abdominal incisions, with 138 (50.4%) patients in Group-A and 136 (49.6%) patients in Group-B. Discharging sinus was found in 3.62% of Group-A vs. 0.73% of Group-B. Burst abdomen was seen in 2.17% patients in Group-A and 1.47% in Group-B [13,16].

In this RCT, the average pain and tenderness in postoperative period in association with both different types of skin suturing were assessed by using the pain and tenderness score respectively. In both groups there was no significant difference in these outcomes, although in Group A relatively better analgesic outcomes were observed. In Group A, approximately on day 03, the average pain score fall below 01, but in group B, the approximate length of it was 5 days after surgery. In question of average tenderness after surgery, in both groups, it was postoperative day 04 when the tenderness was found below 01 (Table 3).

There was a gradual fall of pain from postoperative day 1 to 5 in both groups and at the end of day 5, the pain score was below 01 on an average (Figure 2). In regards to tenderness, on 5th postoperative days, the average tenderness score was found below 1 in both study groups. Again no significant variation of this falling trend was detected in between the both study groups, therefore, the difference of outcomes of average tenderness can be said to be minimal in contrast between both groups (Figure 3).

Conclusion

Monofilament can be a better alternative and the suture material of choice for closure of midline abdominal wound in case of contaminated emergency surgery in contrast to the polyfilament suture in terms of postoperative infective and analgesic outcomes.

References

- Bailey and Love’s (2008) Short practice of surgery, surgical infection. (25th edn.) CRC Press, USA: 1437-1449.

- Leaper DJ, Harding KG, Phillips CJ (2002) Management of wounds. In: Johnson C and Taylor I (eds) Recent Advances in Surgery. (25th edn) RSM Press, London: 13–24.

- Conze J, Klinge U, Schumpelick V (2005) Incisional Hernia. Chirurg 76: 897–909.

- Leaper DJ, Winslet MC (2004) Basic surgical skills and anastomosis. In: Bailey and Love’s Short Practice of Surgery. (24th edn.) CRC Press, USA, 1:98–9, 1186–1190.

- Kirk RM, Williamson RCN (2000) Laparotomy; elective and emergency. In: Krik RM, (Ed). General surgical operations. (4th edn.) Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh: 81–86, 89–92.

- Cusheri A (2002) Disorders of abdominal wall and peritoneal cavity. In: Cusheri A, Steele RJC, Moosa AB, editors. Essential Surgical Practice. (4th edn.) Arnold, London: 143–182

- Rucinski J, Margolis M, Panagopoulos G, Wise L (2001) Closure of midline abdominal fascia. Meta-analysis delineates the optimal technique. Am Surg 67: 421–426. [Crossref]

- Yahchonchy-Chonillard E, Aura T, Piccone O, Etienne JC, Fingerhut A (2003) Incisional hernia, Related risk factors. Dig Surg 20: 3–9. [Crossref]

- Knaebel HP, Koch M, Sauerland S, Diener MK, Büchler MW, et al. (2005) INSECT Study Group of the Study Centre of the German Surgical Society. Interrupted or continuous slowly absorbable sutures, Multi-centre randomized trial to evaluate abdominal closure technique INSECT-Trial. BMC Surg 5: 3.

- Ceydeli A, Rucinski J, Wise L (2005) Finding the best abdominal closure: An evidenced-based review of the literature. Curr Surg 62: 220–225. [Crossref]

- Alicia JM, Teresa CH, Michele L, et al. (1999) Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection. Infect Control Hospital Epidemiol 20: 247-278.

- Van’t Riet M, Steyerberg EW, Nellensteyn J, Bonjer HJ, Jeekel J (2002) Meta-Analysis of technique for closure of midline abdominal incisions. Br J Surg 89: 1350–1356. [Crossref]

- Choudhary SK, Choudhary SD (1994) Mass closure vs. layered closure of abdominal wound: a prospective clinical study. J Indian Med Assoc 92: 229–232. [Crossref]

- McLean S, Kreamer B (2002) Wound care and healing. The Washington manual of Surgery. (3rd edn.) Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, USA: 176–177.

- Hodgson NC, Mathaner RA, Ostbye T (2000) The search for an ideal method of an abdominal fascia closure, a meta-Analysis. Ann Surg 231: 436–442. [Crossref]

- Talpur AA, Awan MS, Surhio AR (2011) Closure of elective abdominal incisions with monofilament, non-absorbable suture material versus polyfilament absorbable suture material. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 23: 51-54. [Crossref]