Abstract

Introduction: Subphrenic abscess diagnosed by CT scan, sometimes remains with unidentified origin. A sealed posterior perforated duodenal ulcer must be considered.

Case report: Here, we report a case of sealed posterior perforated duodenal ulcer revealed by subphrenic abscess in a 49-year-old woman. Abdominal CT scan showed a subphrenic abscess. The elevated level of lipase in drainage fluid, a water-soluble contrast imaging study and the upper digestive tract endoscopy revealed that the subphrenic abscess was secondary to a sealed posterior perforated duodenal.

The treatment consisted of percutaneous drainage of the subphrenic abscess, adapted antibiotics and anti-secretory medication.

Conclusion: Any subphrenic abscess of unknown origin must lead to a search for lipase in drainage fluid, a call for water-soluble contrast imaging study and upper digestive tract endoscopy, looking for sealed posterior perforated duodenal ulcer.

Key words

perforation, duodenal ulcer, subphrenic abscess

Introduction

Perforations are the second most common complication of peptic ulcer disease. They very often occur on the anterior wall of the duodenum or stomach [1]. Posterior perforations are rare and are sometimes revealed by sub-phrenic abscesses [2,3]. They are exceptionally sealed at the moment of the abscess diagnosis. To our knowledge, the world literature reported two documented cases, more than twenty years ago [4,5]. We report a case of sealed posterior perforated duodenal ulcer revealed by a subphrenic abscess in a 49-year-old woman.

Case report

A 49-year-old woman was admitted to the emergency for sharp epigastric pain radiating to the right upper quadrant, which had been lasting for 24 hours then. She presented no feverish state. The patient’s history was unremarkable. She was not taking any nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Her blood pressure was 120/80 mm Hg, her heart rate was 86 beats/minute, and her temperature was 36.5°C. Physical examination revealed tenderness in the epigastrium. Laboratory studies revealed normal white blood cells count and elevated level of C-reactive protein (130 mg/l), procalcitonine (3.9 ng/ml) and D-dimer (1270 ng/ml).

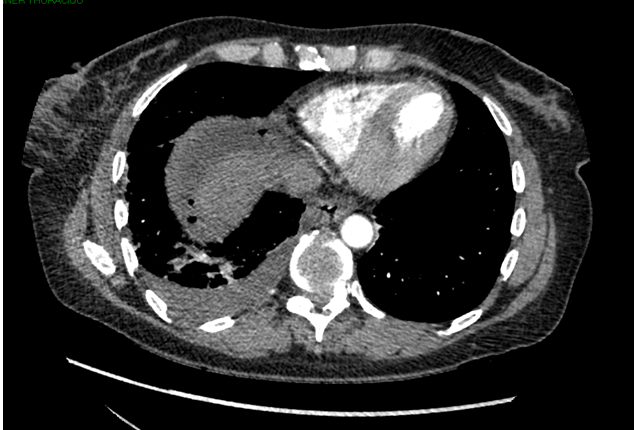

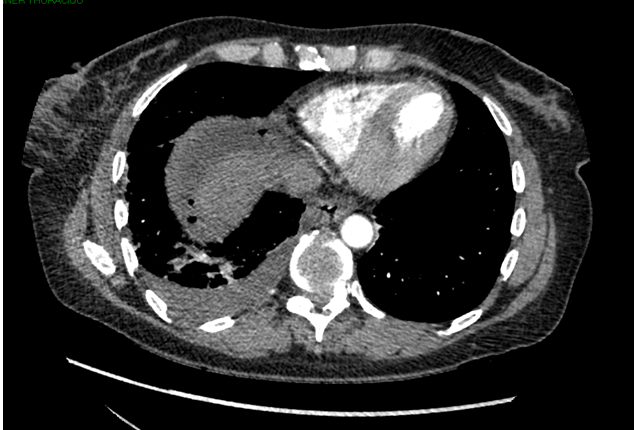

A chest CT scan was made looking for pulmonary embolism. It showed an atelectasis of the right lung base (Figures 1 and 2). The diagnosis of acute bronchopneumonia was made and our patient was given medical therapy with antibiotic (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid). Four days later, our patient was admitted again because of persistent abdominal pains. Physical examination revealed severe tenderness in the epigastrium and in the right upper quadrant. Laboratory studies revealed an elevated white blood cells count (17800 cells/ml). The C-reactive protein doubled (336 mg/l). Procalcitonine was 2.16 ng/ml. On abdominal CT scan, a right sub-phrenic abscess and a condensation of the posterior segment of the right lower lobe clearly depicted (Figure 3). The abscess measured 10 x 10 x 24 cm. There was no free pneumoperitoneum nor free intraperitoneal fluid. A review of the first CT scan revealed a huge air-fluid collection in the subphrenic space (Figures 1 and 2). The diagnosis of right subphrenic abscess was made.

Figure 1. Chest CT scan (axial view) shows an atelectasia of the right lung base and air-fluid collection in the right subphrenic space.

Figure 2. Chest CT scan (sagittal view) shows an atelectasia of the right lung base and air-fluid collection in the right subphrenic and retroperitoneal spaces.

Figure 3. Abdominal CT scan (coronal view) shows a huge air-fluid collection in the right subphrenic space and an atelectasia of the right lung base.

Figure 4. Abdominal CT scan (coronal view) with oral contrast material shows no extravasation of oral contrast material

The subphrenic abscess was drained by percutaneous catheter placement. Approximately 2000 ml of yellowish fluid (secondarily purulent), rich in lipase (1845 UI/l), was obtained in the next few days. Culture of this fluid showed no germ.

The patient was treated with antibiotics (ceftriaxone and metronidazole), a proton pump inhibitor intravenously.

To investigate the cause of the abscess, an abdominal CT scan with oral contrast material was performed. It showed no extravasation of oral contrast material. The patient underwent upper digestive tract endoscopy, which revealed a 10 mm wide ulcer of the posterior wall of the duodenal bulb. Serum Helicobacter pylori antibody was negative. A diagnosis of subphrenic abscess secondary to a sealed posterior perforated duodenal ulcer was made.

Ceftriaxone and metronidazole were changed secondarily by piperacillin-tazobactam and amikacin after 7 days, because of the persistence of elevated level of white blood cells and C-reactive protein.

The clinical course was favorable, the abdominal pain disappeared, and her condition improved rapidly with a decreased level of white blood cells and C-reactive protein. Four weeks later, a repeat CT scan showed residual perihepatic fluid collection which were managed conservatively.

Discussion

Posterior perforations of peptic duodenal ulcer are rare [2]. Its clinical onset may be atypical or can be masqueraded by concurrent therapies (methadone), causing a delay of diagnosis [6]. A posterior perforated ulcer can extravasate and track in the retroperitoneal space or the lesser sac. Local inflammation reaction and fibrosis of the surrounding adherent retroperitoneal tissue tend to seal off these perforations. The spillage and the inflammation were confined to an abscess cavity [3]. Generally, these inflammatory phenomena result in the compartmentalization of the outpoured content into the retroperitoneal in the form of retroperitoneal collections. The occurrence of sub-phrenic abscesses, which is an intraperitoneal collection, might be explained by the localization of the perforations on the posterosuperior wall of the duodenum.

Abdominal CT scan and sonography has been established as the most valuable imaging technique to identify a sub-phrenic abscess, the presence, site and cause of gastrointestinal tract perforation [7,8]. Perforation is usually not completely sealed at the moment of the diagnosis and water-soluble contrast imaging study showed extra-luminal leakage. Its complete seal (self-healing) is exceptional [3]. Biochemical analysis of drainage material become crucial to investigate the cause of the abscess. Indeed, the high quantity of lipase in the drainage fluid is suggestive of peptic ulcer perforation, in the absence of CT scan signs and laboratory testing of severe acute pancreatitis. The present case is being reported because of this particularity. The search for posterior perforation of peptic ulcer must firstly be made by water-soluble contrast imaging study, showing contrast leaking through the perforated duodenum. The absence of contrast leakage suggests that the perforation was sealed. A careful upper digestive tract endoscopy must be then performed to show the duodenal ulcer.

Isolation of more than one microorganism, especially mixed gram negative and anaerobic microorganisms, would suggest the intra-abdominal origin of the abscess formation. On the contrary, the isolation of only one microorganism, as in the present case, may rather suggest that the infection was of haematogenous origin [9]. The culture of drainage fluid was not contributive with our patient. The amoxicillin/clavulanic-acid therapy to our patient to treat her presumed bronchopneumonia was probably the source of the microbial sterilization of the drainage fluid.

Initial management of a subphrenic abscess includes an early percutaneous drainage and empiric broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics. This should be given until culture and sensitivity data are obtained. Once these data are obtained, a therapy with appropriate coverage that is likely to work in the abscess environment should be chosen [10]. Percutaneous drainage should be the treatment of choice because it is less invasive and more cost effective than surgically made [11].

The management of sealed perforated duodenal ulcer is medical. This non-operative treatment strategy should include intravenous antibiotics, nil per mouth and a nasogastric tube, anti-secretory and antacid medication (proton pump inhibitors) [12]. An eradication treatment of Helicobacter pylori is associated to reduce the recurrence risk of ulcer, any time that there is the proof of its infection [13].

Conclusion

Any subphrenic abscess of unknown origin must lead to systematic biochemical and bacterial analysis of drainage fluid. The presence of lipase in the drainage fluid suggests a gastrointestinal tract perforation in absence of acute and severe pancreatitis symptoms, a call for water-soluble contrast imaging study looking for contrast leaking through the perforated duodenum. The absence of contrast leakage suggests that the perforation is sealed and requires a careful upper digestive tract endoscopy to confirm it. The treatment of subphrenic abscess is that of any intra-abdominal abscesses. The treatment of sealed perforated ulcer is non operative.

References

- Lau JY, Sung J, Hill C, Henderson C, Howden CW, et al. (2011) Systematicreview of the epidemiology of complicatedpepticulcerdisease: incidence, recurrence, risk factors and mortality. Digestion84: 102-113.[Crossref]

- Wong CH, Chow PK, Ong HS, Chan WH, Khin LW, et al. (2004) Posterior perforation of pepticulcers: presentation and outcome of an uncommonsurgical emergency.Surgery135: 321-325.[Crossref]

- Camera L, Calabrese M, Romeo V, Scordino F, Mainenti PP, et al. (2013)Perforatedduodenalulcerpresenting with a subphrenicabscessrevealed by plain abdominal X-ray films and confirmed by multi-detector computedtomography: a case report. J Med Case Rep7: 257. [Crossref]

- Romero MJ, Ciriza C, Taxonera C, Alvarez A, Rivero MA, et al. (1995) [Subphrenicabscessrelated to hiddenperforatedduodenalulcer]. An Med Interna 12: 46-47.[Crossref]

- Seniutovich RV, Alekseenko AV, Palianina SI, Melenko AS, Gil' NE (1990) [Treatment of concealedperforatedduodenalulcerscomplicated by subhepaticabscesses]. KlinKhir: 58-59.[Crossref]

- Shen Y, Ong P, Gandhi N, Degirolamo A (2011) Subphrenicabscessfrom a perforatedduodenalulcer. Cleve Clin J Med 78: 377-378.[Crossref]

- Oguro S, Funabiki T, Hosoda K, Inoue Y, Yamane T, et al. (2010) 64-Slice multidetectorcomputedtomographyevaluation of gastrointestinal tract perforation site: detectability of direct findings in upper and lower GI tract. EurRadiol20: 1396-403. [Crossref]

- Fujii Y, Asato M, Taniguchi N, Shigeta K, Omoto K, et al. (2003) Sonographicdiagnosis and successfulnonoperative management of sealedperforatedduodenalulcer. J Clin Ultrasound31: 55-58.[Crossref]

- Caravaca F, Burguera V, Fernández-Lucas M, Teruel JL, Quereda C (2014) Subphrenicabscess as a complication of hemodialysiscatheter-related infection. Case RepNephrol2014: 502019.[Crossref]

- Sirinek KR (2000) Diagnosis and treatment of intra-abdominal abscesses. Surg Infect (Larchmt)1: 31-38.[Crossref]

- Levin DC, Eschelman D, Parker L, Rao VM (2015) Trends in Use of Percutaneous Versus Open Surgical Drainage of Abdominal Abscesses. J Am CollRadiol12: 1247-1250.[Crossref]

- Søreide K, Thorsen K, Harrison EM, Bingener J, Møller MH, et al. (2015) Perforatedpepticulcer. Lancet 386: 1288-1298.[Crossref]

- Ramakrishnan K, Salinas RC (2007) Pepticulcerdisease. Am Fam Physician76: 1005-1012.[Crossref]