Abstract

Background: Blood tests like clotting time and bleeding time are tools that help physicians to predict snake envenomings and their management.

Methods: In this study patients bitten by Bothrops eryhtromelas in Campina Grande, Paraíba, Brazil were analyzed front of blood alterations. Clinical and epidemiological data of those individuals to design which cities show the majority of the accidents were also made.

Results: Pain was the most referred local manifestation by the individuals bitten by the snake B. erythromelas followed by edema. Four patients presented haemorrhage after envenoming returning to normal after treatment. The predominance among male aging between 20 to 30 years old shows that this age range is the most affected by snake bites. In this study was observed the prevalence of the agriculture activity and the rural area. Haemorrhage was the most systemic manisfestation observed in this study.

Conclusion: In the present study we verified the importance of evaluating hematological parameters on snake envenomings in accordance with clinical and epidemiological data.

Key words

epidemiology, snake envenomation, clinics

Introduction

Snake envenomings are a health problem mainly in rural areas of tropical and subtropical countries. In Brazil occur almost 30.000 snake bites annually, resulting in more than 100 deaths (0,4%) [1]. In northeastern Brazil Bothrops erythromelas is the edemic species being responsible for 210 bites in Paraíba. People bitten by Bothrops erythromelas show local effects at the site of the bite like oedema, ecchymosis, blisters and necrosis; systemic manifestations like gengival bleeding, hematuria and epistaxis, as well as blood disturbances [2]. As B. erythromelas venom does not present miotoxic activiy [3] people bitten by this snake don’t present large necrosis at the site of the bite.

As most of envenomed individuals do not see the snake at the moment of the bite and also do not bring the species to the hospital, diagnosis is based on clinical features [4]. Those clinical features also help physicians to classify envenomation as mild, moderate or severe, which will drive the treatment [5]. Local swelling at the site, bleeding and shock are used as prognostic, although those features have not been tested rigorously [4].

Only two works immunologically evaluated individuals bitten by snakes. Barraviera et al. [6] analyzed 31 patients bitten by the snakes Crotalus durissus terrificus and Bothrops jararaca. In that work it was observed an increase of IL-6 and IL-8 in all patients on the first days after envenomation. Laboratorial data showed leukocitosis, leucopenia and neutrofilia. Ávila-Aguero et al. [7] analyzed children bittem by the snake Bothrops asper in Costa Rica and observed a marked raise on IL-6 and IL-8 on admission time, returning after 72 hours treatment. TNF-α showed a peak on 12 hours after admission. RANTES was increased in five patients.

Immunological evaluation after snake bites is not largely studied, as well as, not well known on individuals bitten by snakes. In this work we analyzed the involvement of IL-10, IFN-γ and NO for patients bitten by the snake Bothrops erythromelas in Norteastern Brazil.

Methods

Patients

The project that originated this paper was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital and all patients included in the study consent to participate. Third five patients admitted to the hospital in Campina Grande with clinical diagnosis of Bothrops envenoming were included in this study. After a clinical evaluation, patients were classified as mild, moderate or severe envenomed. The mild group was characterized by a local swelling, local bleeding and mild hemorrage; the moderate goup was characterized by more severe swelling, local bleeding and hemorrage; the sever group was classified as presented severe swelling, local bleeding and blisters, and severe hemorrage. In each group individuals received specific antivenom. The mild group received 4 vials of antivenom, the mild group recieved 8 vials and the severe group received 12 vials of antivenom (as prescribed by the Ministério da Saúde, 2001) [1]. The antivenom therapy was started as soon as possible to all individuals. Patients were studied as far as 48 hours after entrance at the hospital. In order to understand epidemiological features of Bothrops envenomation in PB, information of patients included: name, local of event, time, area (urban or rural), age, sex, as well as site of bite, type of snake, time between bite and entrance at the hospital, haemorrage, swelling, clotting time, platelets number, complete blood count, bleeding time, local necrosis and systemic bleeding.

Blood samples

Individual blood samples (20 ml) were collected by venipuncture on admission, 24 hours and 48 hours after envenomation. Blood coagulation time was assessed using two tubes incubated 30 minutes total at 37°C. Platelets were counted electronically in a automatized system (Counter 19 – Wiener Lab). It is important to clarify that CDC and number of platelets were performed only under medical prescription.

Statistical analysis

Epidemiological evaluations is a transversal study using indirect documentation on snake envenomations attended in Campina Grande from June to December, 2010. All include patients presented medical diagnosis for Bothrops envenomation. Data were collected from the notification sheets of the Poison Information Center of Campina Grande.

Total whole blood cell counting

Total whole blood cell counting (TWBCC) was not possible to analyze statistically once not all patients had this parameter prescribed by the physician. As TWBCC is not predictable for envenomation, physicians prescribe it only in severe cases were patient’s life is at risk. However, this is an important parameter to evaluate, for example, to know the type of leucocytes involved in this envenomation before and after treatment.

Epidemiological evaluation

Epidemiological analysis was carried out in order to evaluate important parameters as local of occurrence of the accident, like rural or urban areas, city of occurrence, sex, age, local of the bite, number of vials used for treatment and time between bite and hospital admission.

The city of Campina Grande is located on Paraíba State, composed by 379.871 people, 46,8% men and 53,2% women [8]. The city is a converge pole, with around 232 neighbors cities, which drive to Campina Grande searching for services offered, including health services [9].

This study took place with help of the Poison Information Centre (CEATOX-Campina Grande), a service offered by the Pharmacy Department of the State University of Paraíba (UEPB) with the partnership of the Regional Hospital of Campina Grande.

Clinical evaluation

Clinical evaluation of all patients was performed by the medical staff of the hospital.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Centro de Pesquisas Aggeu Magalhães/FIOCRUZ, Recife.

Results

Twenty seven patients had a confirmatory diagnosis of Bothrops envenoming based on the clinical observation and laboratorial tests. Sixteen patients were classified as mild envenomation, seven patients were classified as moderate envenomation and three were classified as severe envenomation.

Platelets

Platelet count was as their lowest in only three patients as follows: two mild and one severe envenomation. This data do not corroborate other studies [10] which claims that thrombocytopenia is a marked statistically significant process developed on envenomations by Bothrops species.

Clotting time and bleeding time

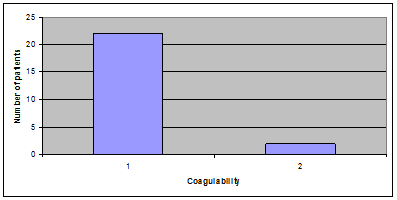

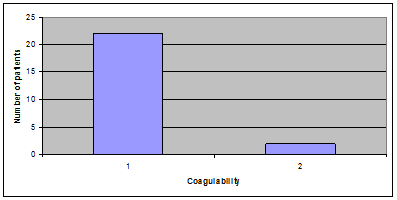

Clotting time was altered in 22 patients raising 12 hours after treatment, except for two of them which were yet incoagulable after treatment (Figure 1). Bleeding time was not altered in any patients.

Figure 1. Coagulability of patients bitten by Bothrops erythromelas snake venom.

Epidemiological evaluation

Table 1 shows the characterization of snake envenomations attended and notified at the CEATOX-PB, following social and demographic variables. When age of patients was evaluated, it was a greater frequency for 20-30 years old group (25%). When age was evaluated it was observed that male was the gender the most affected (89,28%).

Age |

|

0-10 |

0 – 0% |

11-19 |

3 – 10,71% |

20-30 |

7 – 25% |

31-40 |

1 – 3,57% |

41-50 |

5 – 17,85% |

51-60 |

6 – 25% |

61-70 |

3 – 10,71% |

71-80 |

0 – 0% |

81-90 |

1 – 3,57% |

90-100 |

0 – 0% |

n.i. |

1 – 3,57% |

Total |

27 – 100% |

Table 1. Distribution of Bothrops erythromelas snake bites by sex.

The majority of envenomations occurred in the rural area (89,25%) rather than in urban area (10,71%).

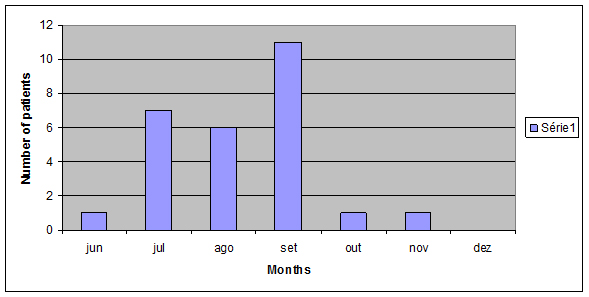

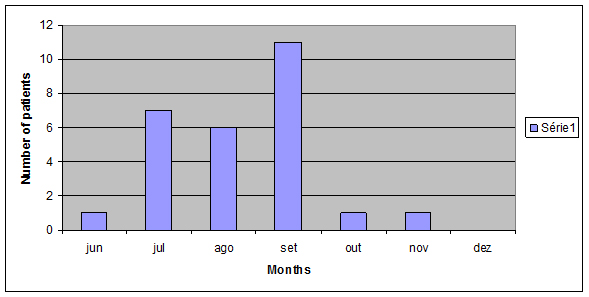

Bites occurred from June to December even though irregularly (Figure 2) and the city with most notifications was Taperoá (3 cases) (data not shown).

Figure 2. Distribution of Bothrops erythromelas bites according to seasonality – from June to December, 2009.

The anatomical region of the bite most affected was feet (46,42%) followed by finger feet (17,85%) and hand finger (10,71%) (Table 3).

Area |

|

Rural |

24 |

Urban |

3 |

Total |

27 |

Table 2. Distribution of snake Bothrops erythromelas bites by area.

Local |

|

Pain |

22 |

Edema |

16 |

Echimosis |

3 |

Necrosis |

0 |

Parestesia |

9 |

Hiperemia |

1 |

Table 3. Anatomical site of bite.

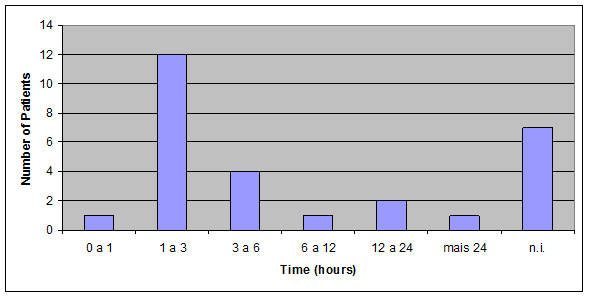

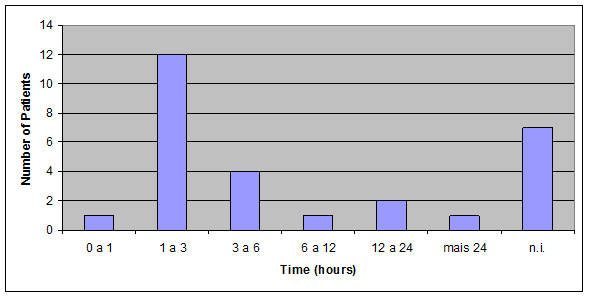

Accidents classified as mild envenomation were the most observed (50%) as we can observe by the number of antivenom vials used (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Time distribution of patients bitten by Bothrops erythromelas – June to December, 2009.

Most patients reached the hospital care into the 3 first hours after envenomation (46,42%) (Figure 3).

Clinical evaluation

Pain was the most referred local manifestation, in 22 patients, followed by edema. Systemic disorders were observed like hemorrhage [4] and head ache [7].

Discussion

Blood platelets play an important role in hemostasis, starting the development of hemostatic plugs [11]. In this study it was observed that of the twenty-seven patients evaluated only 3 presented low levels of platelet counts before treatment. This result is in agreement with previous studies [11,12]. As low levels of platelet counts is related to the severity of envenomation we can suggest that the patients included in this study presented most mild envenomation as their platelet counts were normal.

Sano-martins et al. [13] observed that patients bitten by smaller B. jararaca presented a higher platelet counts which could not be completely understood, as incoagulability is more commonly observed in individuals bitten by smaller than larger B. jararaca.

Simple coagulation tests can be used to diagnose systemic envenoming and control the antivenom doses [14]. This study we observed 81,4% of patients presenting prolonged clotting time (data not shown), which corroborate with other studies [10,15,16], as it is known that Bothrops venoms has the ability of activate blood coagulation [14].

Envenomation inflicted by snakes of the Viperidae family is usually characterized by prominent local effects such as necrosis, haemorrhage, edema and pain [17,18]. Those effects, however, are not well neutralized by the antivenom used [11,19], even though, they are the only effective treatment for snake bite envenomation [20].

In the present study we observed that pain was the most referred local manifestation by the individuals bitten by the snake B. erythromelas (Figure 1), followed by edema (Figure 2). These data corroborate with other studies, either experimental [19,21] or with humans [1,11,22].

There is a high quantity of components on Bothrops venoms that compromise haemostasis. So that it is common a high frequency of bleeding caused by this type of envenomation. Those bleedings can be distinguished as local and systemic [13]. In the majority of the cases bleeding is stopped after antivenom therapy, although some brain bleeding has been related in some cases which can lead patient to death [23].

In the present study 4 patients presented haemorrhage after envenoming returning to normal after treatment. All 4 patients were classified as moderate or severe envenomation and the type of haemorrhage was epistaxis and gingival haemorrhage.

The predominance among male aging between 20 to 30 years old shows that this age range is the most affected by snake bites. These data may indicate the insertion of young men in the work more than women. The Brazilian Ministry of Health data (2003) [24] show that in 52,3% of notifications the prevalence is for 15 to 49 years old, which correspond to the work force. Male were the most exposable to this injury with 70% of the bites (Table 1).

In this study was observed the prevalence of the agriculture activity and the rural area. In Northeast region of Brazil it is observed a greater activity in the planting and harvest periods (Table 2). So that it may have a correlation between the frequency of snake bites and the period for planting and harvest [9]. Those inferences reinforce the fact that snake bites as a work accident. Furthermore, these data confirm the results obtained by Kastiriratne et al. [25] who related that all over the world rural activity is a risk factor for snake bites.

Seasonality for snake bites must be taken as an important fact which can drive educational prevention. In Southern and South of Brazil snake accidents usually occur from October to April which is the most warm and rainy period of the year for those regions (Brazil, 2003) [24]. In Northeastern the accidents occur mostly between May and September with decay after October [9].

Victims were most affected in the inferior members as feet and finger feet. [22] and [26] also related feet (43,1%) as the most affected region of the body. So that the use of protection equipments as gloves and boots are indicated (Table 3).

Mild envenomations were the most observed in this study. This is in accordance with period between bite and hospital care and also with other authors [5,27]. Although [10] showed that time between bite and hospital care is not related.

The most clinical features observed in this study were pain and edema. It is well known that Bothrops evenomings are characterized by pain, edema, haemorrhage, local necrosis, ecchimosis, blisters [1,2] (Table 4).

Local |

|

Pain |

22 |

Edema |

16 |

Echimosis |

3 |

Necrosis |

0 |

Parestesia |

9 |

Hiperemia |

1 |

Table 4. Local manifestations after Bothrops erythromelas snake bite.

2021 Copyright OAT. All rights reserv

Haemorrhage was the most systemic manifestation observed in this study, as also related by other authors [10,28] followed by headaches. This haemorrhage was soon stopped after antivenom therapy, except for one patient who presented epistaxis and remained bleeding for more 2 days after treatment (Table 5).

Systemic |

|

Hemorrhage |

4 |

Thow up-diarrhea |

3 |

Head ach |

7 |

Sleepy |

1 |

Turvation |

1 |

sickness |

1 |

Total |

17 |

Table 5. Systemic manifestations after Bothrops erythromelas snake bite.

Conclusions

In the present study we verified the importance of evaluating hematological parameters on snake envenomings in Northeastern Brazil, specially on Bothrops envenomation. These data will allow us to better understand the variations on the different envenomings as well as to design better approaches on new therapies.

Also, epidemiological data can lead us to corroborate with a more accurate notification for this type of health problem.

References

- Avila-Agüero ML, París MM, Hu S, Peterson PK, Gutiérrez JM, et al. (2001) Systemic cytokine response in children bitten by snakes in Costa Rica. Pediatr Emerg Care 17: 425-429. [Crossref]

- Barraviera B (1995) Acute-phase reactions including cytokines in patients bitten by Bothrops and Crotalus snakes in Brazil. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins 1: 11-22.

- Bucaretchi F, Herrera SR, Hyslop S, Baracat EC, Vieira RJ (2001) Snakebites by Bothrops spp in children in Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 43: 329-333. [Crossref]

- Cardoso JL, Fan HW, França FO, Jorge MT, Leite RP,et al. (1993) Randomized comparative trial of three antivenoms in the treatment of envenoming by lance-headed vipers (Bothrops jararaca) in São Paulo, Brazil. Q J Med 86: 315-325. [Crossref]

- Chacur M, Picolo G, Gutierrez JM, Teixeir CFP, Cury Y (2001) Pharmacological modulation of hyperalgesia induced by Bothrops asper (terciopelo) snake venom. Toxicon 39: 1173-1181. [Crossref]

- Franca FOS, Málaque CMS (2003) Acidente Botrópico. In: Animais Peconhentos no Brasil: Biologia, Clinica e Terapeutica dos Acidentes. Haddad Jr, et al. (Eds.), cap. 6, p. 72-86, ed. Sarvier.

- Gutierrez JM, Chaves F, Gené JA, Lomonte B, Camacho Z, et al. (1989) Myonecrosis induced in mice by a basic myotoxin isolated from the venom of the snake Bothrops nummifer (jumping viper) from Costa Rica. Toxicon 27: 735-45. [Crossref]

- Hutton RA, Warrell DA (1993) Action of snake venom components on the haemostatic system. Blood Rev 7: 176-189. [Crossref]

- Intituto Brasileiro de Geografia e EstatÃstica, 2007.

- Kamiguti AS, Matsunaga S, Spir M, Sano-Martins IS, Nahas L et al. (1986). Alterations of the blood coagulation system after accidental human inoculation by Bothrops jararaca venom. Braz J Med Biol Res 19: 199-204. [Crossref]

- Kamiguti AS, Zuzel M, Theakston RD (1998) Snake venom metalloproteinases and disintegrins: interactions with cells. Braz J Med Biol Res 31: 853-862. [Crossref]

- Kasturiratne A, Wickremasinghe AR, de Silva N, Gunawardena NK, Pathmeswaran A, et al. (2008) The global burden of snakebite: a literature analysis and modelling based on regional estimates of envenoming and deaths. PLoS Med 5: e218. [Crossref]

- Kouyoumdjian JA, Polizelli C, Lobo SM, Guimares SM (1991). Fatal extradural haematoma after snake bite (Bothrops moojeni). Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 85: 552. [Crossref]

- Lemos JC, Almeida TD, Fook SML, Paiva AA, Simões MOS (2009) Epidemiologia dos acidentes ofÃdicos notificados pelo centro de assistência e informação toxicológica de campina grande (Ceatox-CG), ParaÃba. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia 12: 50-59.

- Ministério da Saúde de Brasil (2011) Manual de diagnóstico e tratamento de acidentes por animais peçonhentos. Fundação Nacional de Saúde.

- Moreno E, Queiroz-Andrade M, Lira-da-Silva RM, Tavares-Neto J (2005) Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of snakebites in Rio Branco, Acre. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 38: 15-21. [Crossref]

- Picolo G, Chacur M, Gutiérrez JM, Teixeira CF, Cury Y (2002) Evaluation of antivenoms in the neutralization of hyperalgesia and edema induced by Bothrops jararaca and Bothrops asper snake venoms. Braz J Med Biol Res 35: 1221-1228. [Crossref]

- Ribeiro LA, Jorge MT, Iversson LB (1995) Epidemiology of accidents due to bites of poisonous snakes: a study of cases attended in 1988. Rev Saude Publica 29: 380-388. [Crossref]

- Rosenfeld D (1971) Symptomatology, pathology, and treatment of snako bites in South America. In: Bucherl W, Buckley EE (Eds.), Venomous animals and their venoms. New york. Academic Press, 79. v. 2, p. 345-384.

- Sano-Martins IS, Fan HW, Castro SC, Tomy SC, Franca FO (1994) Reliability of the simple 20 minute whole blood clotting test (WBCT20) as an indicator of low plasma fibrinogen concentration in patients envenomed by Bothrops snakes. Toxicon 32: 1045-1050. [Crossref]

- Sano-Martins IS, Santoro ML, Morena P, Sousa-e-Silva MC, Tomy SC, et al. (1995) Hematological changes induced by Bothrops jararaca venom in dogs. Braz J Med Biol Res 28:303-312. [Crossref]

- Sano-Martins IS,Santoro ML (2003) Distubios hemostaticos em envenenamentos por animais peconhentos no Brasil. In: Animais Peconhentos no Brasil. Biologia, Clinica e Terapeutica dos Acidentes. (1stedn), Sao Paulo: Sarvier; 289-309.

- Santoro ML1, Sousa-e-Silva MC, Gonçalves LR, Almeida-Santos SM, et al.(1999) Comparison of the biological activities in venoms from three subspecies of the South America rattlesnake (Crotallus durissus terrificus, C. durissus cascavella and C. durissus collilineatus). Comp Biochem Physiol C Pharmacol Toxicol Endocrinol 122: 61-73. [Crossref]

- Santoro ML1, Sano-Martins IS, Fan HW, Cardoso JL, Theakston RD, et al. (2008) Haematological evaluation of patients bitten by the jararaca, Bothrops jararaca, in Brazil. Toxicon 15: 1440-8. [Crossref]

- Teixeira Cde F, Fernandes CM, Zuliani JP, Zamuner SF (2005) Inflammatory effects of snake venom metalloproteinases. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 100: 1812-1814. [Crossref]

- Vasconcelos CM, Valença RC, Araújo EA, Modesto JC, Pontes MM, et al. (1998) Distribution of 131I-labeled Bothrops erythromelas venom in mice. Braz J Med Biol Res 31: 439-443. [Crossref]

- Warrell DA (2010) Snake bite. Lancet 375: 77-88. [Crossref]