Abstract

Change in levels of vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF) isoforms is a feature of diabetic retinopathy. To better characterize the expression of VEGFa and VEGF165bisoforms in the diabetic retina and to explore how oxidative stress influences the balance between these molecules, we have used the Ins2Akita mouse model of diabetes. Retinal tissue collected from wild-type and Ins2Akita mice, together with D407 retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells were used as experimental models. The retina of the Ins2Akita diabetic mice was shown to have decreased levels of the anti-angiogenic VEGF165b protein and a high production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). High glucose deregulated the expression of VEGF proteins as well as the production of ROS in RPE cells. Physiological levels of H2O2 were found to preserve the equilibrium between VEGF isoforms in RPE cells while pathological levels down-regulated the VEGF165b. Besides hyperglycemia, oxidative stress also contributes to disrupt the equilibrium between pro- and anti-angiogenic factors in the retina, a profile frequently found in retinal pathologies.

Keywords

angiogenesis, VEGF, retina, diabetic retinopathy, oxidative stress

Abbreviations

AMD – age-related macular degeneration; BRB – blood-retinal barrier; DR – diabetic retinopathy; PEDF – pigment epithelium-derived factor; RPE – retinal pigment epithelial; ROS – reactive oxygen species; VEGF – vascular endothelial growth factor

Introduction

Angiogenic growth factors are essential in several physiological processes, such as the growth of new blood vessels in wound healing or organ repair, but are also the main contributors in pathological angiogenesis [1,2]. The vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGF) encompass a large family of angiogenic factors, being the VEGF-A (or normally referred as VEGF) one of the most potent members. Alternative splicing of the VEGF mRNA results in several isoforms: the VEGFxxx and the VEGFxxxb isoforms (where xxx denotes the number of aminoacids) [3]. In general, VEGFxxxb are well established as the anti-angiogenic isoforms of the VEGF family [4]. These anti-angiogenic factors are abundantly expressed in normal tissues but down-regulated in pathologies associated with abnormal angiogenesis, such as cancer and some retinal diseases [3-5]. Specifically, VEGF165b binds the VEGF receptor 2, the same receptor as VEGF, with the same affinity. This binding, however, does not activate the receptor, preventing the subsequent signaling pathways [3]. Previous studies have shown that VEGF is increased in the eyes of diabetic patients, contributing to angiogenesis and neovascularization [6-8]. In fact, an imbalance between pro- and anti-angiogenic factors has been described in some ocular diseases but, the precise mechanism how this arises remains not fully elucidated.

In the retina, VEGF is expressed in different cell types including retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cells or endothelial cells [7,9]. According with these studies, VEGF levels increased upon inflammatory stimuli or hypoxia, all influenced by oxidative stress. High glucose-mediated oxidative stress has also a role upon the levels of VEGF (review in [7]). However, data regarding the effect of oxidative stress upon anti-angiogenic VEGF isoforms are missing.

Oxidative stress occurs within biological systems as a result of an excess of reactive oxygen species (ROS), either by an increase in its production or due to impaired antioxidant defences. It is well recognized that, in most cases, oxidative stress has a deleterious effect upon cells and tissues and, presently, ROS are described as one of the main contributors to different diseases such as hypertension [10,11] or diabetes [12-14]. ROS has also been implicated in both physiological and pathological angiogenesis [15-17]. Nevertheless, it is also recognized that, apart from ROS adverse effects they also have a role as signalling molecules, particularly H2O2[17,18]. The thin line that separates the two opposing roles of ROS is related to concentration as well as time of exposure. Another aspect to consider is the type of ROS, since different ROS can induce different cellular responses. Among the several ROS, H2O2 is a small and uncharged molecule which rapidly diffuses across biological membranes, thus being suitable to act as a signaling and second messenger molecule. It was shown in RPE cells that, in a physiological state, the levels of VEGF and the pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) are balanced. However, when retinal cells were exposed to H2O2, the equilibrium between both factors was disrupted and, it was suggested that this fact might contribute to choroidal neovascularization in age-related macular degeneration (AMD) [19]. Interestingly, in a recent in vivostudy, it was demonstrated that low levels of superoxide anion were able and required to stimulate angiogenesis through a VEGF-dependent pathway in a model of peripheral artery disease [15]. In order to contribute to the elucidation of key players in diabetic retinopathy (DR), the present study aims to better characterize the expression of VEGF isoforms in retinal cells in diabetic conditions. This study also intends to explore the contribution of oxidative stress, namely H2O2, to the balance between VEGF isoforms in the retina.

Materials and methods

Animals

Six-months old C57BL/6 (wild-type) and Ins2Akita (diabetic) mice (The Jackson Laboratory, USA) housed under controlled temperature and a 12 h light/dark cycle with food and water ad libitumwere used for the in vivo experiments. Diabetic phenotype was confirmed 3-months after birth by measuring blood glucose from a drop of blood from a tail puncture (Freestyle Precision, Abbot, USA), and animals used in this study exhibited blood glucose ≥ 500 mg/dl. All experimental procedures were carried out according to the Portuguese and European Laboratory Animal Science Association (FELASA) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, the European Union Council Directive 2010/63/EU for the use of animals and the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) for the use of animals in ophthalmic and vision research. Animals were humanely sacrificed by cervical dislocation, the eyes were enucleated and the retinas were extracted by dissection of the eyeball. Isolated retinas were processed depending on the experiment.

Cell culture

D407 cells, a human retinal pigment epithelial (RPE) cell line used in the in vitroexperiments, were kindly provided by Dr. Jean Bennett from the University of Pennsylvania (USA). Cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2-95% air at 37ºC and were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM)(Sigma-Aldrich, USA) supplemented with 1% Penicilyn/Streptomicyn (Sigma-Aldrich), 1% Glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich) and 5% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich). For sub-culturing, cells were dissociated with a trypsin-EDTA solution (Sigma-Aldrich), split 1:10 and cultured in culture plates with 21 cm2 growth areas (Orange Scientific, Belgium). Culture medium was changed every 2 days, and cells reached confluence after 3 daysof incubation. For the experiments regarding glucose effects, cells were culture in 6-well plates for 3 days either in DMEM with 5.5 mM glucose (low glucose medium, LG) or in DMEM with 25 mM glucose (high glucose medium, HG). Cells were also grown in DMEM with 25 mMmannitol (high mannitol medium, HM) which was used as an osmotic control. For the experiments regarding oxidative stress effects, cells were treated with H2O2 or t-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BHP), concentrations up to 500 µM during approximately 16h (overnight treatment), to mimic a chronic exposure.

Immunoblotting

Isolated retinas from C57BL/6 and Ins2Akita mice were homogenized in ice-cold lysis RIPA buffer (50 mMTris-HCl pH 7.4, 1% NP-40, 0.25% Na-deoxycholate, 150 mMNaCl and 1 mM EDTA) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail. D407 RPE cells were gently washed with PBS and also homogenized in the previous lysis buffer. Cells and retinas were incubated on ice for 20 min and after centrifugation (16200 g, 20 min, 4°C) the supernatant was collected and protein concentration determined using a protein assay kit (BioRad, USA) with bovine serum albumin as standard. Protein samples were mixed with 4x SDS sample buffer, boiled for 5 min at 95°C and equal amounts of protein were loaded and subjected to electrophoresis (100V, 2h) in a 12% sodium dodecyl sulphate acrylamide gel. After proteins were electrotransferred (20V, 20 min) onto polyvinylidinedifluoride (PVDF) membranes the transblot sheets were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS-T (0.1%Tween-20) for 1h at room temperature. Membranes were incubated with the following primary antibodies: VEGF (ref. ab46154, Abcam, UK) diluted 1/1000, VEGF165b (ref. ab14994, Abcam) diluted 1/500, p22phox (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) diluted 1/1000 and catalase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) diluted 1/500. Incubations were performed overnight at 4°C in 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS-T. The membranes were subsequently washed with TBS-T and then incubated with the respective secondary antibody conjugated with horseradishperoxidase, 1/5000 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1h at room temperature. The membranes were washed with TBS-T during 20 min and incubated with the enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagent (GE Healthcare, Sweden) for 5 min. To ensure that samples were evenly loaded the membranes were stripped and re-probed for tubulin (1/1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Membranes were visualized in a GelDoc system (BioRad).

Immunocytochemistry

Cells at a density of 60000 cells per well were grown overnight in glass coverslips at 37ºC. Cells were gently washed with PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) for 15 min at room temperature. Cells were subsequently washed two times with PBS and permeabilized and blocked with 10% normal serum in PBS-T (0.2% TritonX-100) for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were simultaneously incubated with primary antibodies for VEGF (Abcam) and VEGF165b (Abcam) both diluted at 1/500 in PBS-T overnight at 4ºC. Cells were washed three times with PBS-T and two fluorescent secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor® 594 and Alexa Fluor® 488 (Life Technologies, USA), both diluted 1/2000 in PBS-T; 1h at room temperature) were used for signal detection. In the secondary antibodies solutions was included DAPI, in order to stain the nuclei. Cells were visualized using a fluorescence microscope at a 40x magnification (Axio Observer Z2, Zeiss).

Cellular viability assay

Cells were grown in a 48 well plate at a density of 15000 cells per well during 3 days. The 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT, Sigma-Aldrich) solution (5 mg/ml) was added to each well and incubated during 4h at 37ºC. Subsequently the supernatant was discarded and replaced with a mixture of 0.04N HCl/isopropanol to dissolve the formed blue formazan crystals. The plate was furtherincubated for 15 min at 37ºC. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm (maximal formazan absorption) and 630 nm (absorption for cellular debris and well imperfections) using a microplate reader (InfiniteM200, TECAN). Cellular viability was calculated by subtracting absorbance measurements taken at 570 nm for those at 630 nm.

Measurement of ROS levels

ROS levels were measured using the general oxidative stress probe CM-H2DCFDA (Life Technologies). Cells were grown at 10000 cells per well in 96-well plates during 3 days in LG, HG and HM culture media. Cells were washed with PBS and loaded with 10 µM CM-H2DCFDA for 30 min at 37ºC. For the measurement of ROS levels in the retinal tissue, isolated retinas were homogenized in ice-cold RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail and incubated on ice for 20 min. Retinas were briefly centrifuged and homogenates were loaded with 50 µM CM-H2DCFDA in 96-well plates during 60 min at 37ºC. Fluorescence intensity was measured in a microplate reader (InfiniteM200, TECAN) at excitation 494 nm and emission 522 nm during 60 min. The relative ROS levels were expressed as arbitrary fluorescence units.

Statistical analysis

Arithmetic means are given with standard error of the mean. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired t-test and one-way analysis of variance followed by the Newman–Keuls test for multiple comparisons. A value of P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

3.1 Imbalance between VEGF isoforms and ROS levels in the retina of Ins2Akita mice

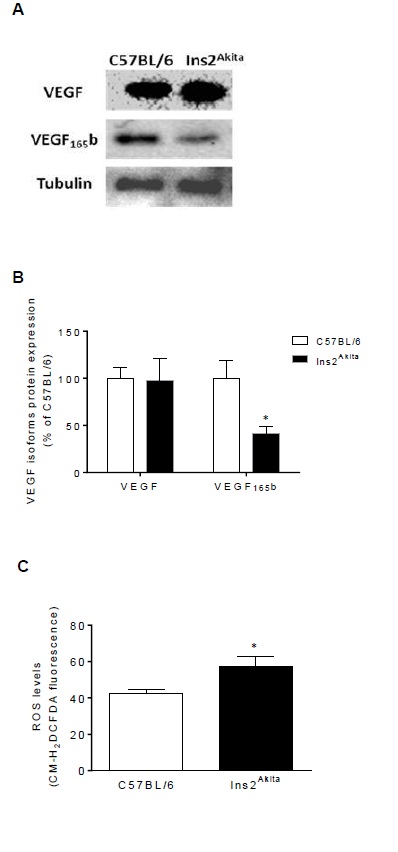

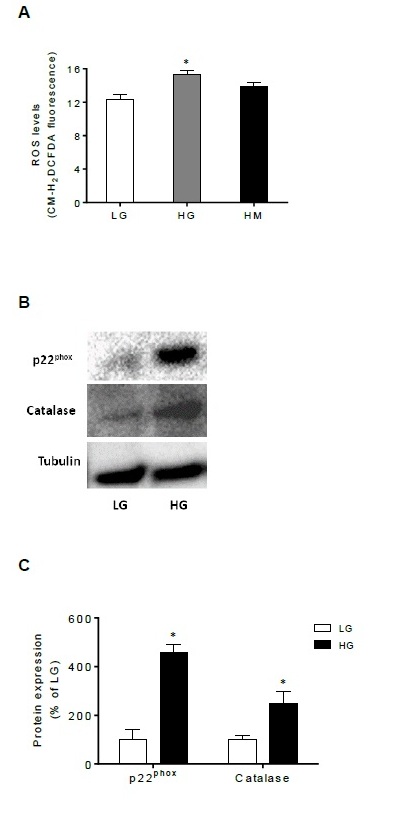

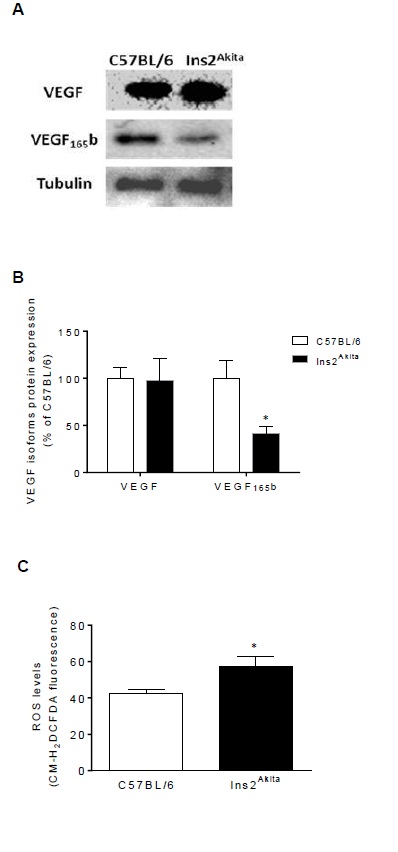

Expression of VEGF and VEGF165b was evaluated in retinal tissue collected from 6-months old wild-type and diabetic mice (Figure 1A and 1B). As can be observed, upon comparison with normoglycaemic mice, the expression of VEGF was virtually unchanged in the retina of 6-month old diabetic mice while the expression of the anti-angiogenic VEGF165b isoform was highly reduced. Additionally, the presence of ROS was also assessed in retinal tissue from wild-type and diabetic mice by means of the CM-H2DCFDA probe (Figure 1C), and it was found that retinas from Ins2Akitahave increased levels of ROS when compared with those from wild-type mice.

Figure 1: VEGF isoforms and ROS levels are imbalanced in the retina of 6-monthsold diabetic mice. (A) Representative immunoblots and (B) Densitometric analysis of VEGF and VEGF165b expression normalized to β-tubulin in the retinal tissue collected from 6-months old wild-type (C57BL/6) and diabetic mice (Ins2Akita) (n=4). *P<0.05 compared with C57BL/6 values, determined by Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison Test. (C) ROS levels in retinal tissue collected from 6-months old wild-type and diabetic mice (n=5). *P<0.05 compared with C57BL/6 values, determined by an unpaired t-test.

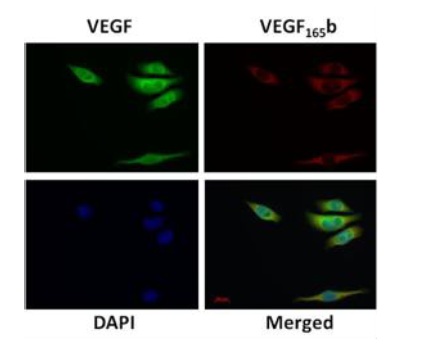

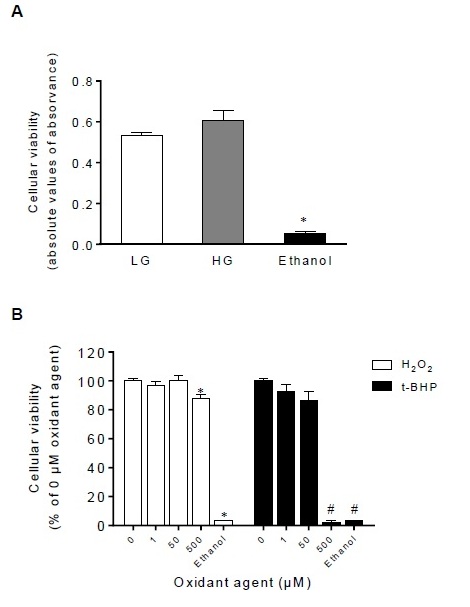

Glucose and low levels of oxidants do not impair the viability of RPE cells

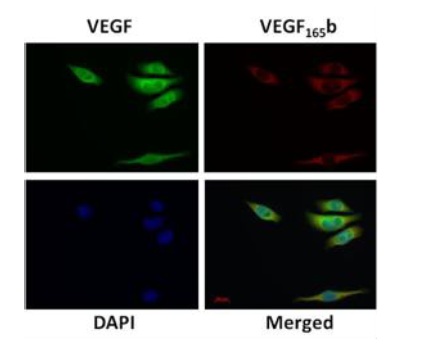

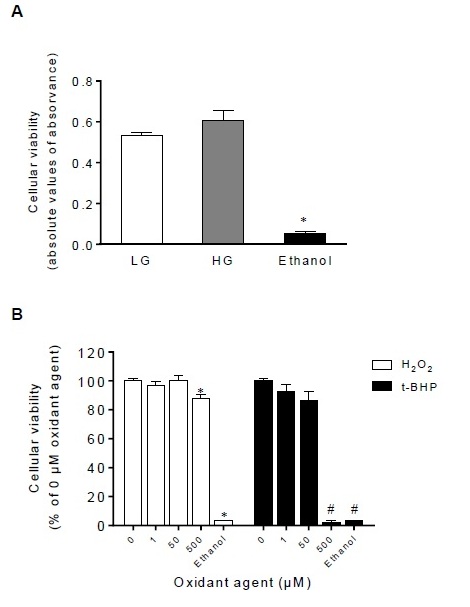

In order to better understand the mechanisms responsible for the imbalance between VEGF isoforms in retinal cells in a diabetic environment, we subsequently used an invitro experimental model of RPE cells. D407 RPE cells were assessed for theexpression of VEGF isoforms and it was found that both VEGF and VEGF165b are expressed in this cell line and co-localize predominantly in the cytoplasm but also in the perinuclear space of RPE cells (Figure 2). In order to mimic an in vitrohyperglycemic environment, D407 RPE cells were exposed to different glucose concentrations [Low Glucose (LG) – 5.5 mM and High Glucose (HG) – 25 mM]. Figure 3A shows that the viability of RPE cells was not affected by glucose treatment. As the negative control for cellular viability, ethanol induced a significant cell death (Figure 3A). To evaluate the effect of ROS upon retinal cells, D407 were treated with either H2O2, a naturally occurring ROS or synthetic t-BHP, widely used to induce oxidative stress. Cells were treated with different concentrations of H2O2 and t-BHP, namely 1 µM as aphysiological concentration and 50 and 500 µM simulating pathological concentrations, during 16h to mimic a chronic exposure. Figure 3B shows that the viability of D407 RPE cells was compromised by 500 µM of H2O2 and t-BHP but not by lower concentrations of both oxidant agents. Concentrations of t-BHP equal to 500 µM induced a negative effect upon the viability of D407 RPE cells as ethanol. On the other hand, concentrations ranging from 1 to 50 µM of both H2O2 and t-BHP demonstrate to be safe for RPE cells and were hereafter used.

Figure 2: VEGF and VEGF165b proteins co-localize in RPE cells. Cellular localizationof VEGF and VEGF165b in D407 RPE cells assessed by immunocytochemistry. Cells were double-stained with anti-VEGF (green, 1/500 Abcam) and anti-VEGF165b (red, 1/500 Abcam) and counter-stained with DAPI to visualize the nuclei (blue). Images were obtained with a fluorescence microscope and a 40x magnification. Scale bar = 20 µm. Images are representative of three independent experiments.

2021 Copyright OAT. All rights reserv

Figure 3: Glucose and low levels of oxidants do not impact the cellular viability ofRPE cells. (A) Viability of D407 RPE cells grown in the presence of LG (5.5 mM glucose) and HG (25 mM glucose) during three days (n=5). *P<0.05 compared with LG and HG values, determined by Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison Test. (B) Viability of D407 RPE cells grown in the presence of oxidant agents (H2O2 and t-BHP) during 16h measured by means of the MTT assay. Ethanol was used as the negative control for viability (n=5). *P<0.05 compared with 0 µM H2O2values and #P<0.05 compared with 0 µM t-BHP values, determined by Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison Test.

Glucose and ROS modulate the balance between VEGF isoforms in RPE cells

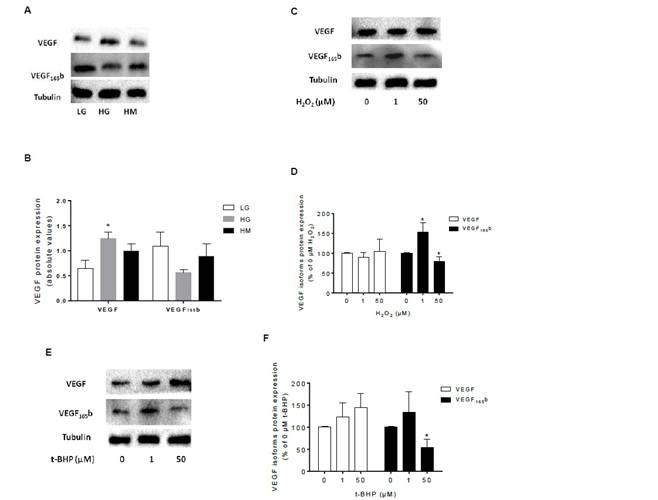

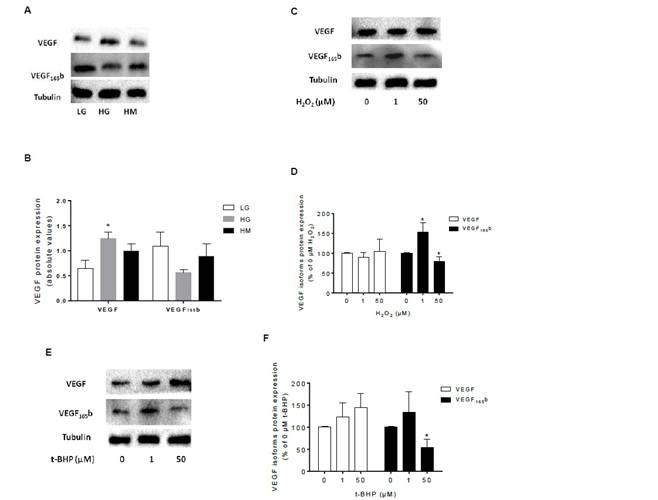

Since glucose and low levels of oxidants did not affected the viability of RPE cells, cells were exposed to either hyperglycemic or oxidative stress conditions. Results regarding these experiments are depicted on Figure 4. As can be observed, high glucose induced an overexpression of intracellular VEGF protein. Simultaneously, high glucose showed a trend to decrease the expression of intracellular VEGF165b in RPE cells. When cells were grown in culture medium supplemented with 25 mMmannitol, expression of both VEGF isoforms was not changed in RPE cells, compared with 5.5 mM glucose (Figure 4A and 4B). RPE cells were exposed to H2O2 and t-BHP (1 and 50 µM) and assessed for VEGF isoforms expression and the obtained results are depicted in Figure 4C-4F. Although intracellular VEGF remains virtually unchanged with H2O2 treatment, it is noticeably evident that 1 µM of H2O2 increases the expression of VEGF165b while high concentrations of H2O2 has the opposite effect promoting a decrease of this anti-angiogenic factor in RPE cells (Figures 4C and 4D). The same trend was observed when retinal cells were exposed to t-BHP, namely the inhibition of VEGF165b in the presence of high concentrations of oxidant (Figures 4E and 4F).

Figure 4: Glucose and ROS modulate the expression of VEGF isoforms in RPE cells.(A) Representative immunoblots and (B) Densitometric analysis of VEGF and VEGF165b expression normalized to β-tubulin in the presence of LG (5.5 mM glucose), HG (25 mM glucose) and HM (25 mMmannitol) in D407 RPE cells (n=4). *P<0.05 compared with LG values, determined by Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison Test. (C) Representative immunoblots and (D) Densitometric analysis of VEGF and VEGF165b expression normalized to β-tubulin in the presence of H2O2 (0, 1, 50 µM; 16h of exposure) in D407 RPE cells (n=4). *P<0.05 compared with 0 µM H2O2 values, determined by Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison Test. (E) Representative immunoblots and (F) Densitometric analysis of VEGF and VEGF165b expression normalized to β-tubulin in the presence of t-BHP (0, 1, 50 µM; 16h of exposure) in D407 RPE cells (n=4). *P<0.05 compared with 0 µM t-BHP values, determined by Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison Test.

Glucose induce ROS production in RPE cells

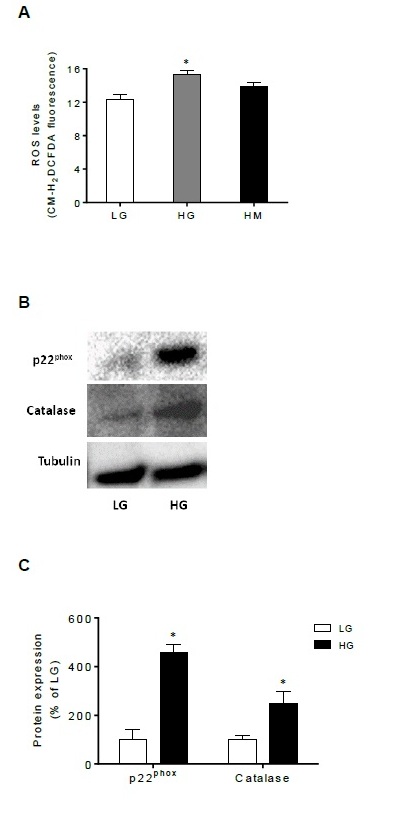

Levels of ROS were measured in the presence of low and high glucose concentrations as well as in the presence of mannitol in D407 RPE cells (Figure 5). Figure 5A shows that ROS levels increase as glucose concentration increases and also shows that mannitol had no significant effect when compared with glucose conditions. As can be observed in figures 5B and 5C, high glucose concentrations induced overexpression of p22phox enzyme. In addition, the expression of the antioxidant enzyme catalase is also activated by glucose in RPE cells (Figure 5B and 5C).

Figure 5: Glucose increases oxidative stress in RPE cells. (A) ROS levels in thepresence of LG (5.5 mM glucose), HG (25 mM glucose) and HM (25 mMmannitol) in D407 RPE cells (n=4). *P<0.05 compared with LG values, determined by Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison Test. (B) Representative immunoblots and (C) Densitometric analysis of p22phoxand catalase expression normalized to β-tubulin in the presence of LG (5.5 mM glucose) and HG (25 mM glucose) in D407 RPE cells (n=3). *P<0.05 compared with LG values, determined by Newman-Keuls Multiple Comparison Test.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates an imbalance between VEGF isoforms in the retina of an in vivomodel of diabetes – the Ins2Akita mouse. The results obtained with the RPE cells show that in addition to glucose, ROS levels also contribute to modulate the expression of VEGF isoforms in the retina.

The Ins2Akita mouse, a model extensively used for the study of diabetes and diabetes-associated complications, shows evidences of hyperglycemia approximately at 4 weeks of age and retinal complications around 12 weeks after the onset of hyperglycemia [20-22]. In the present study it was used retinal tissue collected from 6-months old mice, a time-point where the diabetic mice demonstrate features of retinal disease [21]. Angiogenic growth factors such as VEGF, are critical for several physiological processes, but are also the main growth factors associated with pathological angiogenesis. On the other hand, the anti-angiogenicVEGFxxxb isoforms are down-regulated in pathologies associated with abnormal angiogenesis, including some retinal diseases [3-5]. In the present study, the expression of VEGF was virtually unchanged in the retina of 6-month old diabetic mice while the expression of VEGF165b was highly reduced, comparing with the normoglycaemic mice. Previous studies with the Ins2Akita mice have shown a similar trend concerning pro- and anti-angiogenic factors in the retina [22]. These authors did not detect significant differences at 6-months of age but found an imbalance between the expression of VEGF and PEDF in the retinas of 9-months old diabetic mice [22]. It is suggested that the loss of anti-angiogenic factors in the retina might occur at earlier stages of the disease and it might be an event that precedes the overexpression of angiogenic factors. It is well recognized that a common feature of several ocular diseases is an imbalance between pro- and anti-angiogenic factors in retinal cells [23,24]. The results of the present study reinforce those ones previously described by others and show for the first time that the levels of VEGF165b are also down-regulated in retinal cells in the context of diabetes.

Our data demonstrate that retinas from the Ins2Akita exhibit increased levels of ROS. In DR, hyperglycaemia generates ROS and triggers angiogenic responses [12,13]. Altogether, our results show an imbalance between the VEGF isoforms in the retina of the diabetic mice and also show that these retinas are in a condition of oxidative stress. These changes were evident at a time-point where the diabetic mice show retinal complications, suggesting that both the balance between the VEGF isoforms and the oxidative stress status of the retina might contribute to the process of retinal disease. Interestingly, it has recently been shown by others that the high oxidative stress found in the retinal tissue of diabetic mice correlates with the increased expression of VEGF and also with pro-inflammatory molecules [25].

The in vitrostudies were designed to better explore the mechanisms responsible for the imbalance between the VEGF isoforms in the retina in the context of diabetes. RPE cells are one of the main constituents of the blood-retinal barrier (BRB) and alterations in this structure play a central role in the development of retinal diseases, including DR [26,27]. D407 RPE cells are a spontaneously transformed cell line that was previously obtained by others from a primary culture of human RPE cells [28]. It was found that RPE cells co-localize the VEGF and VEGF165b proteins. Although expression of VEGF proteins has been previously described in several in vitroretinal cells [29,30] the co-localization of VEGF and VEGF165b in D407 RPE cells was unknown. Previous studies have also shown that in culture RPE cells, VEGF165 is one of the predominant isoforms expressed, from all the members of the VEGF family [29,30]. RPE cells were exposed to different glucose concentrations to mimic a physiological (5.5 mM) and a diabetic (25 mM) condition and it was found that VEGF and VEGF165b were differently regulated by glucose. In the presence of high glucose VEGF was up-regulated and, in opposition, VEGF165b was down-regulated. This effect was not a consequence of high osmolarity because when RPE cells were grown in the presence of high mannitol (25 mM) no change was observed upon the expression of both growth factors. Additionally, it was previously demonstrated that high glucose increased the expression of VEGF while decreased the expression of PEDF protein and mRNA in rat retinal cells, namely in Müller cells [31]. The results obtained with the RPE cells revealed a similar trend than those obtained with the in vivomodels, mainly in what concerns the expression of VEGF165b in the retina, in an environment with excess of glucose. This aspect seems important and reinforce the meaning of using in vitroRPE cells to study molecular mechanisms that otherwise would be impossible.

Oxidative stress induces damaging effects upon cells and tissues and, currently ROS are described as one of the main contributors to different disorders. Nevertheless, H2O2 has been described as either an oxidant or signaling molecule [17,18]. Schröderet al. properly reviewed the nature of H2O2 as a signaling and oxidative molecule within biological systems [18]. According with these authors, the physiological range of intracellular H2O2 must be approximately 1 – 15 µM [18]. Based on the latter, in the present study the effect of two concentrations of oxidants was tested: 1 µM represents a physiological concentration, while 50 µM mimics pathological levels. We found that both H2O2 and t-BHP had no significant effect upon VEGF expression, while the effects of these oxidants upon VEGF165b were quite evident and similar between each other. At a physiological concentration, both oxidants increased VEGF165b expression, while its expression was reduced in the presence of higher concentrations. These results suggest that low levels of ROS such as H2O2 might be important to regulate the expression of VEGF proteins in physiological conditions. It was previously demonstrated by others that high levels of H2O2 (200 µM) down-regulate PEDF mRNA in pericytes [32]. Actually, low levels of endogenous H2O2 are important for normal physiological functioning and signaling, while elevated levels are associated with disease [18]. Additionally, low levels of ROS are essential to support the physiological angiogenesis process of healthy vasculature. Nevertheless, uncontrolled ROS production will promote tissue damage and has been implicated in the development of numerous diseases, including diabetes and its associated complications [17,33,34]. Increased ROS and deregulation of pro-oxidant/antioxidant enzymes has been described as one of the links between elevated glucose and the other metabolic abnormalities found in diabetes-associated diseases. In the present study we demonstrate that high glucose increased ROS in RPE cells. This might result from the overexpression of the p22phox induced by glucose. p22phox is one of the two membrane-associated subunits of the NADPH oxidase family and one of the main endogenous sources of ROS in the vasculature [17]. The expression of catalase was also activated by glucose, probably in an attempt to balance the p22phox levels. Retinal cells, namely the photoreceptors, produce ROS in the presence of certain stress conditions and it was verified that NADPH oxidases were involved in the production of ROS by these cells [35].

Although a direct correlation between the data obtained with the RPE cells and retinal tissue should be done carefully, since the retina encompass different cell types, our data with RPE cells gave important evidences concerning angiogenic factors present in the retina and which are imbalanced in DR. In summary, it was demonstrated that in the presence of physiological H2O2 levels, the VEGF isoforms are balanced, while in the presence of high H2O2 this equilibrium is deregulated, disfavoring the expression of the anti-angiogenic isoforms. In general, we have verified that hyperglycemia unbalances the VEGF isoforms but, in addition, the levels of ROS have also a role upon this equilibrium. Therefore, besides the intracellular glucose concentrations also the intracellular oxidative stress status should be tightly controlled in retinal cells in order to establish adequate levels of VEGF isoforms.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) with individual grants to S. Simão (SFRH/BPD/78404/2011), D. Bitoque (PD/BD/52424/2013), S. Calado (SFRH/BD/76873/2011), GA Silva (EXPL-BIM-MEC-1433-2013, PIRG05-GA-2009-249314–EyeSee). FCT Research Center Grant UID/BIM/04773/2013 CBMR 1334.

References

- Hoeben A, Landuyt B, Highley MS, Wildiers H, Van Oosterom AT, et al.(2004) Vascular endothelial growth factor and angiogenesis. Pharmacol Rev56: 549-580. [Crossref]

- Potente M, Gerhardt H, Carmeliet P (2011) Basic and therapeutic aspects of angiogenesis. Cell 146: 873-887. [Crossref]

- Woolard J, Wang WY, Bevan HS, Qiu Y, Morbidelli L, et al. (2004) VEGF165b, an inhibitory vascular endothelial growth factor splice variant: mechanism of action, in vivo effect on angiogenesis and endogenous protein expression. Cancer Res64: 7822-7835. [Crossref]

- Bates DO, Cui TG, Doughty JM, Winkler M, Sugiono M, et al.(2002) VEGF165b, an inhibitory splice variant of vascular endothelial growth factor, is down-regulated in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res 62: 4123-4131. [Crossref]

- Konopatskaya O, Churchill AJ, Harper SJ, Bates DO, Gardiner TA (2006) VEGF165b, an endogenous C-terminal splice variant of VEGF, inhibits retinal neovascularization in mice. Mol Vis12: 626-632. [Crossref]

- Aiello LP, Avery RL, Arrigg PG, Keyt BA, Jampel HD, et al.(1994) Vascular endothelial growth factor in ocular fluid of patients with diabetic retinopathy and other retinal disorders. N Engl J Med331: 1480-1487. [Crossref]

- Caldwell RB, Bartoli M, Behzadian MA, El-Remessy AE, Al-Shabrawey M, et al.(2003) Vascular endothelial growth factor and diabetic retinopathy: pathophysiological mechanisms and treatment perspectives. Diabetes Metab Res Rev19: 442-455. [Crossref]

- Wang X, Wang G, Wang Y (2009) Intravitreous vascular endothelial growth factor and hypoxia-inducible factor 1a in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol148: 883-889. [Crossref]

- Adamis AP, Shima DT, Yeo KT, Yeo TK, Brown LF, et al.(1993) Synthesis and secretion of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor by human retinal pigment epithelial cells. BiochemBiophys Res Commun193: 631-638. [Crossref]

- Montezano AC, Touyz RM (2012) Molecular mechanisms of hypertension--reactive oxygen species and antioxidants: a basic science update for the clinician. Can J Cardiol28: 288-295. [Crossref]

- Touyz RM, Briones AM (2011) Reactive oxygen species and vascular biology: implications in human hypertension.Hypertens Res34: 5-14. [Crossref]

- Giacco F, Brownlee M (2010) Oxidative stress and diabetic complications.Circ Res107: 1058-1070. [Crossref]

- Araki E, Nishikawa T (2010) Oxidative stress: A cause and therapeutic target of diabetic complications. J Diabetes Investig1: 90-96. [Crossref]

- Maritim AC, Sanders RA, Watkins JB 3rd (2003) Diabetes, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: a review. J BiochemMolToxicol17: 24-38. [Crossref]

- Bir SC, Shen X, Kavanagh TJ, Kevil CG, Pattillo CB (2013) Control of angiogenesis dictated by picomolar superoxide levels. Free RadicBiol Med63: 135-142. [Crossref]

- LelkesPI, Hahn KL, Sukovich DA, Karmiol S, Schmidt DH (1998) On the possible role of reactive oxygen species in angiogenesis. AdvExp Med Biol454: 295-310. [Crossref]

- Kim YW, Byzova TV (2014) Oxidative stress in angiogenesis and vascular disease. Blood 123: 625-631. [Crossref]

- Schröder E, Eaton P (2008) Hydrogen peroxide as an endogenous mediator and exogenous tool in cardiovascular research: issues and considerations. CurrOpinPharmacol8: 153-159. [Crossref]

- Ohno-Matsui K, Morita I, Tombran-Tink J, Mrazek D, Onodera M, et al. (2001) Novel mechanism for age-related macular degeneration: an equilibrium shift between the angiogenesis factors VEGF and PEDF. J Cell Physiol189: 323-333. [Crossref]

- Robinson R, Barathi VA, Chaurasia SS, Wong TY, Kern TS (2012) Update on animal models of diabetic retinopathy: from molecular approaches to mice and higher mammals. Dis Model Mech5: 444-456. [Crossref]

- Barber AJ, Antonetti DA, Kern TS, Reiter CE, Soans RS, et al. (2005) The Ins2Akita mouse as a model of early retinal complications in diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci46: 2210-2218. [Crossref]

- Han Z, Guo J, Conley SM, Naash MI (2013) Retinal angiogenesis in the Ins2(Akita) mouse model of diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci54: 574-584. [Crossref]

- Simó R, Carrasco E, García-Ramírez M, Hernández C (2006) Angiogenic and antiangiogenic factors in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Curr Diabetes Rev2: 71-98. [Crossref]

- Ogata N, Nishikawa M, Nishimura T, Mitsuma Y, Matsumura M (2002) Unbalanced vitreous levels of pigment epithelium-derived factor and vascular endothelial growth factor in diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 134: 348-353. [Crossref]

- Rojas M, Zhang W, Xu Z, Lemtalsi T, Chandler P, et al. (2013) Requirement of NOX2 expression in both retina and bone marrow for diabetes-induced retinal vascular injury. PLoS One8: e84357. [Crossref]

- Cunha-Vaz J1, Bernardes R, Lobo C (2011) Blood-retinal barrier. Eur J Ophthalmol21: S3-S9. [Crossref]

- Xu HZ, Song Z, Fu S, Zhu M, Le YZ (2011) RPE barrier breakdown in diabetic retinopathy: seeing is believing. J OculBiol Dis Infor4: 83-92. [Crossref]

- Davis AA, Bernstein PS, Bok D, Turner J, Nachtigal M, et al.(1995) A human retinal pigment epithelial cell line that retains epithelial characteristics after prolonged culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci36: 955-964. [Crossref]

- Ford KM, Saint-Geniez M, Walshe T, Zahr A, D'Amore PA (2011) Expression and role of VEGF in the adult retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci52: 9478-9487. [Crossref]

- Geisen P, McColm JR, King BM, Hartnett ME (2006) Characterization of barrier properties and inducible VEGF expression of several types of retinal pigment epithelium in medium-term culture. Curr Eye Res31: 739-748. [Crossref]

- Mu H, Zhang XM, Liu JJ, Dong L, Feng ZL (2009) Effect of high glucose concentration on VEGF and PEDF expression in cultured retinal Müller cells. MolBiol Rep36: 2147-2151. [Crossref]

- Amano S, Yamagishi S, Inagaki Y, Nakamura K, Takeuchi M, et al. (2005) Pigment epithelium-derived factor inhibits oxidative stress-induced apoptosis and dysfunction of cultured retinal pericytes. Microvasc Res 69: 45-55. [Crossref]

- Kowluru RA, Mishra M (2015) Oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage and diabetic retinopathy. BiochimBiophysActa 1852: 2474-2483. [Crossref]

- Wan TT, Li XF, Sun YM, Li YB, Su Y (2015) Recent advances in understanding the biochemical and molecular mechanism of diabetic retinopathy. Biomed Pharmacother74: 145-147. [Crossref]

- Bhatt L, Groeger G, McDermott K, Cotter TG (2010) Rod and cone photoreceptor cells produce ROS in response to stress in a live retinal explant system. Mol Vis16: 283-293. [Crossref]