Abstract

Rectal prolapse is a benign condition well-recognized in children. Known complications of the rectal prolapse in children include recurrent mucosal ulceration, bleeding and proctitis. We report a case of a 4-year-old child with rectosigmoid prolapse complicated with sigmoid necrosis and associated with pararectal herniation of ileum between the 2 walls of the prolapsed rectosigmoid. This extremely uncommon event led to strangulation of the ileal segment within the prolapsed rectosigmoid walls. Rectosigmoid prolapse with preoperative diagnosis of sigmoid necrosis has not been previously reported in children. Early diagnosis of the condition and prompt surgical intervention may help to improve the outcome.

Key words

rectal prolapse, necrosis, ileum, sigmoid, surgery

Introduction

Rectal prolapse, a benign condition in children, is defined as the protrusion of the layers of the rectal wall through the anal canal. It may be partial (mucosal) or complete (full-thickness) [1,2]. The term rectal prolapse implies a full-thickness circumferential descent of rectum through the anus. Known complications of the rectal prolapse in children include recurrent mucosal ulceration, bleeding, and proctitis [3].

We hereby report an extremely rare case of rectosigmoid prolapse complicated with ileal and sigmoid necrosis in a 4-year-old child.

Case report

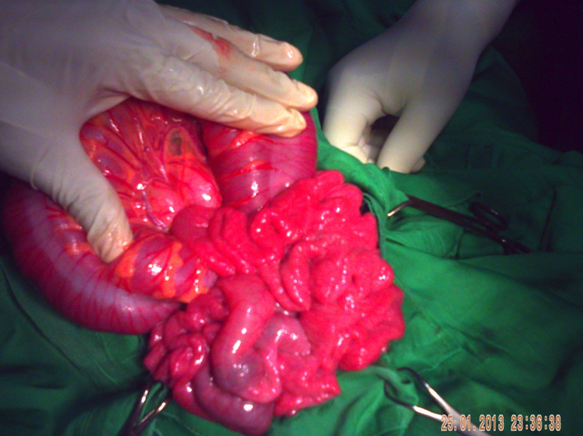

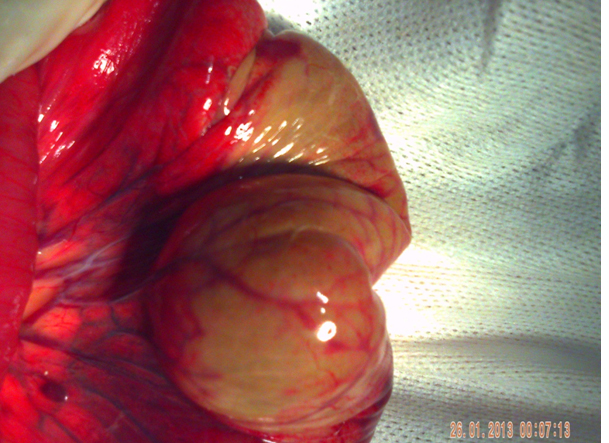

A 4-year-old male child presented to the emergency of the department of general surgery with a 4-day history of a mass protruding through the anus after a bout of acute gastroenteritis. There was no history of rectal prolapse. The patient appeared ill, weak and severely dehydraded. His temperature was 39°C. Physical examination showed abdominal distension without signs of peritoneal irritation. Local examination of the anus revealed rectum and sigmoid, protruding through the anus, dusky, edematous and congested. The sigmoid was ischemic (Figure 1 and 2). The diagnosis of rectosigmoid prolapse complicated with sigmoid necrosis was made. No imaging was performed.

Figure 1. Dusky, edematous and congested rectosigmoid, protruding through the anus.

2021 Copyright OAT. All rights reserv

Figure 2. Rectosigmoid prolapse with ischemic sigmoid.

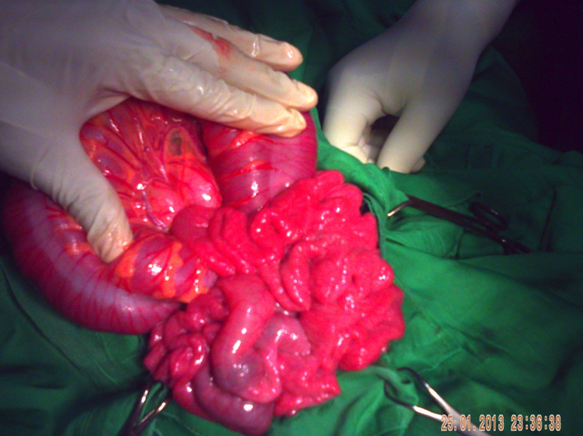

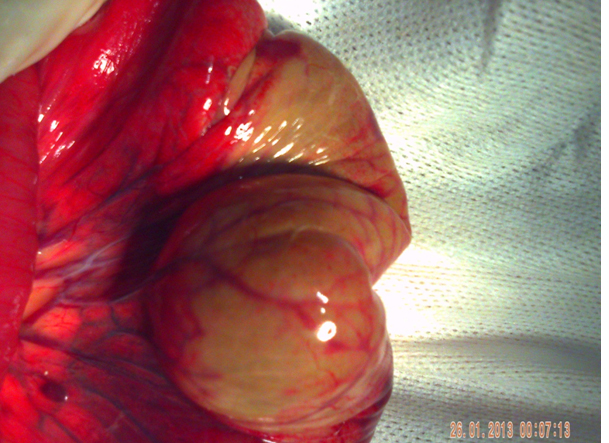

After intravenous fluid resuscitation, a laparotomy was performed. On exploration, the large bowel up to descending colon was dilated. Small bowel was not dilated. The rectum and sigmoid were found prolapsed through the anus (Figure 3). There is neither peritonitis nor intraperitoneal free fluid. The prolapse was reduced from without inward into the peritoneal cavity. After reduction, the sigmoid and ileum were noted to be strangulated in the peritoneal cavity (Figures 4 and 5). Resection of the strangulated sigmoid and strangulated segment of ileum were done. Primary ileal and colic end to end anastomosis were performed.

Figure 3. Intraoperative photograph showing dilated large bowel up to descending colon. Small bowel was not dilated.

Figure 4. Strangulated sigmoid.

Figure 5. Strangulated small bowel.

The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient was discharged 7 days after surgery. At 24-month follow-up, our patient is asymptomatic. There is no sequelea such as fecal incontinence and colic stenosis.

Discussion

Rectal prolapse is a relatively common condition in children [4,5]. Children are predisposed to this condition caused by anatomic considerations: a more vertical course of the rectum with less prominent angulation, flatter coccyx, poor levator support, and a relatively low position of the rectum in the pelvis. Their rectal mucosa is loosely adherent to the underlying smooth muscle [6]. Rectal prolapse in children is thought to begin as mucosal prolapse starting at the mucocutaneous junction. When the precipitating cause of the rectal prolapse is not removed, the rectal prolapse may extend to the sigmoid. The resulting excessive traction on the sigmoid mesocolon and the sigmoid mesocolon strangulation by the levator muscles and anal sphincters, have compromised the vascularization and the necrosis of the sigmoid in our patient. The sigmoid necrosis may also result from dessication or compression of the sigmoid and its mesocolon, by a pararectal hernia sometimes associated with rectal prolapse [2]. Preoperative diagnosis of sigmoid necrosis has not been previously reported in children. The present case is being reported because of its rarity.

Complete rectal prolapse is associated with a constellation of distinct anatomic changes, including a diastasis of the levator muscles, a deep pouch of Douglas, a redundant rectosigmoid colon, a lax lateral and posterior rectal attachments, an elongated mesorectum, and a loss of the usual horizontal lie. This supports the sliding hernia theory of rectal prolapse in which the pouch of Douglas forms the hernial sac. Small bowel (ileum) slid into the hernia sac formed between the prolapsed walls of the rectosigmoid [2]. The strangulation of the pararectal hernia by the levator muscles and anal sphincters leads to vascular compromise and necrosis of the ileal segment contained in the hernial sac, as it is the case of our patient. Preoperative diagnosis of pararectal hernia is sometimes possible. On palpation, bowel loops can be felt within the prolapsed rectal walls. An erect plain abdominal radiograph can reveal the presence of small bowel obstruction [2].

In these patients, most of the time in poor general condition, the resection of strangulated bowel segments (ileum and sigmoid) with diverting double-barrel ileostomy and Hartmann procedure are recommended [2,7]. We performed ileal and colic anastomosis because of the excellent vascularization of proximal and distal end of the ileum and the sigmoid, the absence of peritonitis, and the difficulties of stoma care that we would have been facing, as most of our colleagues in african setting [8].

Conclusion

Rectosigmoid prolapse complicated with ileal and sigmoid necrosis is an extremely rare condition. Because the literature does not reveal such similar cases, the management protocols are not well established. Early diagnosis of the condition and prompt surgical intervention may help to improve the outcome.

References

- Fox A, Tietze PH, Ramakrishnan K(2014)Anorectal conditions: rectal prolapse. FP Essent419:28-34.

- Singh S, Pandey A, Kureel SN, Ahmad I, Srivastava NK (2010) Complicated rectal prolapse in an infant: strangulatedpararectalhernia. J PediatrSurg45: e31-33.[Crossref]

- Sengar M, Neogi S, Mohta A (2008) Prolapse of the rectum associated with spontaneous rupture of the distal colon and evisceration of the small intestine through the anus in an infant. J PediatrSurg43: 2291-2292.[Crossref]

- Ismail M, Gabr K, Shalaby R (2010) Laparoscopic management of persistent complete rectal prolapse in children. J PediatrSurg45: 533-539.[Crossref]

- Laituri CA, Garey CL, Fraser JD, Aguayo P, Ostlie DJ, et al. (2010) 15-Year experience in the treatment of rectal prolapse in children. J PediatrSurg45: 1607-1609.[Crossref]

- Ghorbel S, Chouikh T, Yengui H, Charieg A, Nouira F, et al. (2013) Place de la sclérothérapie dans le traitement du prolapsus rectal récidivant de l’enfant : à propos de 15 cas. Journal de pédiatrie et de puériculture 26:157-60.

- Ravikumar R, Robb A, Jawaheer G (2008) Small boweleviscerationthrough the rectum in childhood. J PediatrSurg43: 562-563.[Crossref]

- Traore A, Diakite I, Togo A, Dembele BT, Kante L, et al. (2010) [Stoma use in the general surgery service of CHU Gabriel Touré]. Mali Med25: 52-56.[Crossref]

2021 Copyright OAT. All rights reserv

2021 Copyright OAT. All rights reserv