Introduction

The Island of Sri Lanka lies 3 degrees north of the equator, 82 degrees east of Greenwich and 32 KM southeast of India. She occupies 65,610 sq. Km (approximately 25,000 sq. miles).Archeological excavations proved that the pre-historic inhabitants in Sri Lanka long pre-dated the human settlements in the other parts of the world. They have found five human skulls, which were identified as 37,000 years old by carbon dating in U.S.A at the Pahiyangala Rock cave site in the Kalutara district in Western Province, though Sri Lanka’s documented history spans only 3,000 years.

Sri Lanka was known by various names by foreigners; Taprobane by the Greeks, Serendib by the Arabs, Ceilao by the Portuguese, Ceylan by the Dutch and Ceylon by the British; Europeans also called this Island “Eden’s Park in the East”. Asian countries that had close connections with Sri Lanka had different names: Siamese (Tibetans) “Swargiya Lanka” (Heaven Lanka), Chinese “Rathna dvipa (Gem Island), Romans as “SwarnaDvipa” (Golden Island).Ancient Sri Lankans called this Island “Heladiva”,”Lanka dvipa”, Lanka etc. With the promulgation of the new constitution in 1972, the name was officially changed its name as The Democratic Socialist republic of Sri Lanka or in short “Sri Lanka”.

The history of medicine in Sri Lanka has been fashioned over the centuries by a synthesis of several intrinsic and extrinsic factors, some of which were unique to the country. Being an island, Sri Lanka is insulated to a large extent from external forces influencing medicine. Diseases being as old as mankind, prehistoric man in Sri Lanka would have evolved his own approach to sickness which need not necessarily have invoked the use of herbs and other drugs. The history of medicine in Sri Lanka can be divided in to major historical periods in its ruled. Thereare:Pre-historic period, Medical Practices under Sri Lankan kings, The Portuguese period (1517-1656), The Dutch period (1656-1796), The British period (1796-1948) and the modern era.

There is hardly any information on the state of medicine in Pre-historic time. It is traditionally believed that Ravana, the prehistoric Emperor of Lanka of Ramayana fame was well-versed in medical lore.His superior acquaintance in Sanskritcan be evaluated from Sivathandawa Sthothra and further he was a proficient Ayurvedic Physician. The art of distilling of Arka and the preparation of Asawa was his invention states Ayurvedic history. He invented the ‘Varuni’ machine to brew Arka. Rawana was the founder of “Sindhuram” medicine. These medicine cured wounds instantly. He was known as Vaidya Shiromani as he rendered valuable service to Ayurveda. He was a divine pharmacologist and a Dhayana yogi.

Sri Lanka has its unique own Ayurvedic medical system and it has been practiced for many centuries in the island nation. The Sri Lankan Ayurvedic tradition is a mixture of the Sinhala traditional medicine, Ayurveda and Siddha systems of India, Unani medicine of Greece through the Arabs, and most importantly, the Desheeya Chikitsa, which is the indigenous medicine of Sri Lanka.

The earliest system of medicinethatprevailedinSriLankawasdesiyachikitsawhichwashandeddownfromgenerationto generation.Reputed or most important prescriptions “RahasVattoru”were preserved secrets of a physician family. This secrecy was one of themanyreasons for the decline of the system,forat times the possessor oftheprescription died without bequeathing it to the nextofkin.

The basis of treatment was largely the application of specific medicinal herbs prepared in various ways.Pastes consisting of crushed medicinal leaves, balk, roots and flowers were the most prevalent recipes for skin diseases. Bathing the affected part of the skin with an embrocation of herbs was another commonly practiced way of treatment[1].

Concept of hospital

Hospital concepts were unknown inancient civilizations such as those of Egypt,Assyria,BabylonandChina.The Sinhalese medical tradition records back to pre-history. Besides a number of medical discoveries and inventions that are only now being acknowledged by western medicine, the ancient Sinhalese are perhaps responsible for introducing the concept of hospital to the world. According to the Mahawansa, the ancient chronicle of Sinhalese royalty written in the 6th century AC. King Pandukabhaya (4th century BC) had lying-in-homes and hospitals (Sivikasotthi-Sala) built in various part of the country after having established his capital at Anuradhapura.This is the most important earliest literary evidence we have of the concept of hospitals (i.e. a special Centre where a number ofpatients was collectively housed and treated until they recovered) anywhere in the world [1-3]

According to the Mahavamsa writer that there were eighteen hospitals at the time of Dutthagamani (161-137 B.C.). The chronicle also refers to the construction of hospitals in the reigns of Buddhadasa (337-365 A.D.), Upatissa I (365-406 A.D.), Mahanama (406-428 A.D.), Dhatusena (455-473 A.D.), Udaya I (797-801 A.D.), Sena I (833-853 A.D.), Sena II (853-887 A.D.), Kashyapa IV (898-914 A.D.), Kashyapa V (914-923 A.D.), Mahinda IV (956-972 A.D.) and Parakramabahu I (1153-1186 A.D.). The remainingancient inscriptional evidence confirms some of these constructions[2,3].

There are ample amounts of archaeological data available pertaining to hospitals attached to monasteries for ailing monks and laymen. Presentlyremaining ruins of hospitals at Mihintale, Anuradhapura, Madirigiriya, Dighavapi and Dombegoda can be dated to the late Anuradhapura period (9th century). Those of the hospital at the Alahana Parivena Complex at Polonnaruwa can be assigned to the twelfth century[1,3]

HospitalsatMihintale(9thcenturyA.D.)andAlahana (11th century AD) have nowbeenidentified, confirmed and reconstructed. Excavation of thesesiteshas yielded valuable informationregardingthepracticeofmedicineandsurgeryinearlytimes. The Mihinthale hospital which has distinction of being the oldest hospital yet discovered in any part of the world, was quite a complex structure(Figures 1 and 2). This hospital is believed to be founded by King Sena 11(853-887 AD) on the basis of evidence in the Chulawamsa. Apieceofequipment or stamp whichisnowconsideredthe hallmark for the identification ofanancient hospital in Sri Lanka is themedicinetrough or behethoruwa(Figure 3).Other than that, this unique structure andthe layout of the building and surgical instrument prove this beyond doubt.Heinz E Muller-Dietz (HistoriaHospitalium 1975) describes Mihinthale Hospital as being perhaps the oldest in the world. As shown by recent archeological excavations, the hospital complex was comprised oftwo main parts: an outer and inner court. The rooms used for the preparation and storage of medicines and the hot water bath were situated in the outer court. The discovery of stone querns used in the grinding of the herbs in the outer court area suggests that the preparation of medicines took place where about. The inner court of this hospital was surrounded by a number of cells where the patients appear to have been treated. A slab inscription of Mahinda 1V (956-972 AD) near the hospital alludes to physicians; physicians who apply leeches and dispensers of medicine to treat skin diseases and other ailments[2-4].

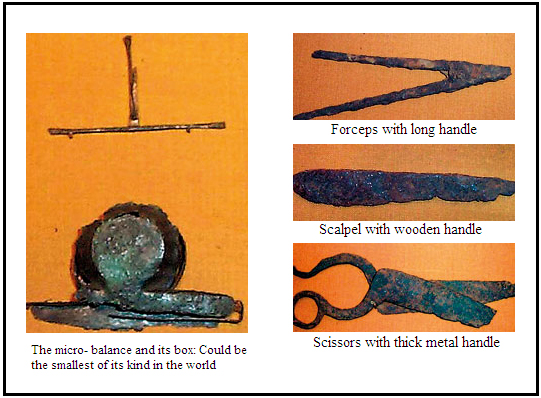

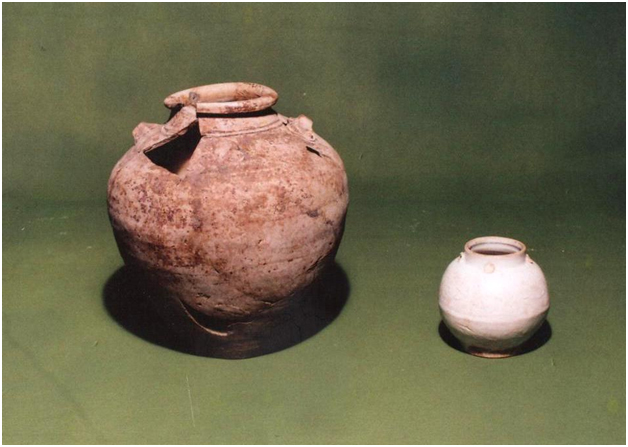

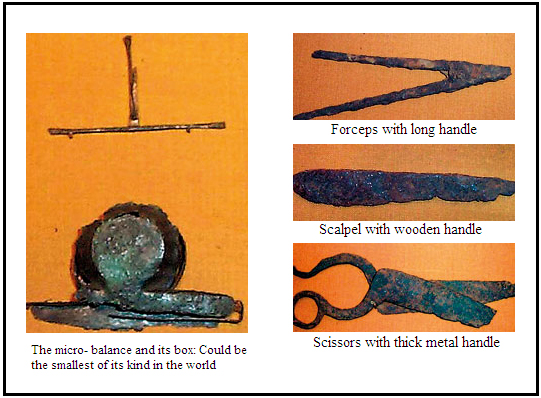

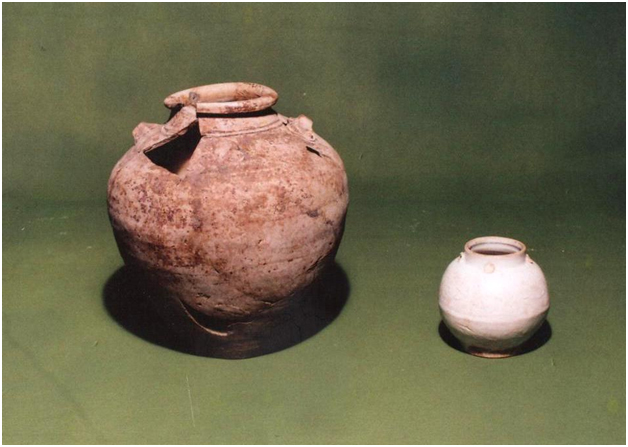

The construction of the Alahana Parivena hospital complex at Polonnaruwa,attributed to Physician-KingParakramabahu 1 (12th century), has been restored by the Cultural Triangle in 1982(Figure 4).The rooms of inmates are of varying sizes and each of them seems to have accommodated a number of inmates. There had been an image house at the center of the courtyard facing these rooms. Unlike in other hospitals, the baths and toilets for the inmates had been constructed just adjoining their rooms(Figure 5). Excavations at the Polonnaruwa hospital site have revealed medicine grinders, a pair of scissors, ceramic jars for the storage of medicines and a hooked copper instrument which was probably used for incising abscesses(Figure 6 and 7).

Figure 1. Mihinthale Hospital (Sri Lanka) as being perhaps the oldest in the world

Figure 2. 9th centuryMihinthale ancient hospital was quite a complex structure

Figure 3. The hallmark for the identification ofanancient hospital in Sri Lanka is themedicinetrough or behethoruwa

Figure 4. AlahanaParivena hospital complex at Polonnaruwa (12th century) has been restored by the Cultural Triangle in 1982

Figure 5. AlahanaParivena hospital - the attached baths and toilets for the inmates

Figure 6. Instruments which was probably used for surgical purposes

Figure 7. Ceramic jars for the storage of medicine

Medicinetrough and immersion therapy

According to ancient Ayurvedabooks, metal,wood,or stone arethematerialfromwhichbathsweremade. In ancient Hospitals where generationsofpatients had to be treated.Theywould haveusedthe long-lasting stone troughs inpreferencetowoodwhichwouldrotwithtimeormetalwhich was likely to corrode withcertain medicinal fluids. There are five surviving medicine troughsthat have been discovered in ancient hospital sites in the buried cities ofMihintale, Medirigiriya, Alahana,Anuradhapura and Dighavapi.

These unique granitemedicinal bath tubs standing on a granite base have not being found anywhere in the ancient civilized societies. Heartwood is carved in a way that repeats the shape of the head, tapering at the neck, expands at shoulders and then slightly tapering at the place where the hands ends, thereby demonstrating the proper proportions of the human body. There is much scientific merit inthisdesign asthe patient could becompletely immersedinitwiththeminimumamountofthe precious medicinalfluid is required for treatment.

A method of special interest was immersion therapy, which was practiced for dermatological conditions as well as other diseases, such as rheumatism, piles, snake bite and fever. A wide choiceofbath fluids, which included embrocationof nativemedicinal herbs, milk, ghee, oilsandvinegar, was prescribed. The mode of action was thought to be fomentation or absorption of the medicinal fluid through the skin. Therewasskepticisminwesternmedicalcirclesuntilrecenttimesabout the ability of medicinal oilstopenetratethat intact normal skin. Nowsuchdoubtshavebeendispelled,agoodexamplebeingtheexternalapplication ofnon steroid anti-inflammatory agents anoilbasefor various rheumatic joint involvements and various topical agents for numerous inflammatory dermatoses[3,5,6].

European Influence and first dermatologic case report in Sri Lanka

Out of the three Europeans nations who govern Ceylon (previously Sri Lanka), the British most influenced the history of dermatology, as in other fields of medicine in the country. Two early British writers, Dr. John Davy and Dr. HenryMarshall,both internationally well-knownmedicalprofessionalswhoworkedin Ceylon,haveleftsome notes of dermatologic interest in their still preserved writings.

Davy was on the staff of the British army in Ceylon from 1816 to 1820. The British governor at the time, General Sir Robert Brownrigg, was much hampered in his wars by a skin ailment he suffered more than 3 years.He was treated by Dr.Davy and a Dr. C Farrell.Probably the first dermatologic case report in Sri Lanka is found in a proclamation issued by them on January 6, 1820 regarding the condition of Sir Robert:

The complaint first made its appearance in the hands and feet, spread to the legs and even extended above the knees. The characterof it more resembledPrurigo than any other disease of the skin: the eruption waspapular, bright red,itchedinsufferably,dischargedconsiderably, andthepartsaffectedweregenerallymuch swollen- many different modes of treatmentwere tried-butwith little success [7].

Sir Robert'scondition, which waselsewhere described asMalabar itch [7], wasprobably scabies, a condition that wasespeciallycommon inthetropical countries.

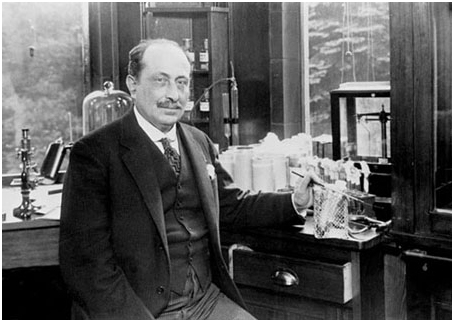

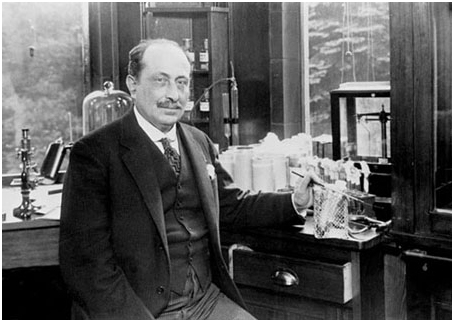

Aldo Castellani

Dermatology is a young specialty in Sri Lanka and it has come a long way since its inception. The first reference to academic Dermatology in Sri Lanka dates back to the period of Sir Aldo Castellani (1902-1915), who rendered his services as a lecturer in Dermatology at the Ceylon Medical College in addition to his work as Professor of Pathology, Head of the Bacteriological Institute and Director of the clinic for tropical diseases [3] (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Sir Aldo Castellani

He found that “pethi gomara”, the golden beauty spots of Sri Lankan women, the praises of which were often sung by ancient Sinhala bards, were but caused by a fungus ( Pityriasisversicolor) [8]. He described anoccupationalskin diseasenamed copra itch, which was very similar to scabies but caused by a mite.It affected workers whohandled copra, thedried kernel of the coconut,which wasfoundto be teeming with theseminuteinsects [9]. He also madesignificant contributionsto the fungal skin diseases component in dermatology. Even today, he will be best remembered by the dermatology community for Castellani’s paint[l0], which had been used until recently for the treatment of dermatophyte infection.

History of Leprosy disease control in Ceylon

Leprosy is referred to in the ancient chronicle Mahavamsa[5], and also several old medical books carry descriptions of the disease.There is a popular belief that a collosal statue (“Kushtarajagala”) carved out of living rock and found in the south of the country (Weligama – Southern province) is that of a leper king, but this view is now disputed by archaeologists(Figure 9).In Sri Lanka management of leprosy commenced with the segregation of patients in 1701 and the first initiative taken by the Dutch administration was the setting-up of the Leper Asylum at Hendala. It was completed in 1708, and exists until very recently as the Government Leprosy Hospital, Hendala(Figure 10).The construction of the Leper Asylum at Hendala, though it was undertaken during the time of Governor Cornelius JoanSimons, was completed only during the time of his successor in office, Hendrick Becker (1707-1716).

Figure 9.Thacollosal statue (“Kushtarajagala”) carved out of living rock (Southern province – Sri Lanka)

Figure 10. Leper Asylum at Hendala (Sri Lanka)

The Lepers’ Ordinance was introduced in 1901 mandating segregation and anti-Leprosy Campaign was established in 1954[11].

History of venereal disease control in Ceylon

Venereal disease in general and syphilis in particular have been mentioned in an ancient Ayurvedic medical book of Ceylon, the Sairiatha Sangrahava, composed in the 5th century A.D. (De Silva, 1913). Since the diseases are mentioned it is reasonable to infer that they did in fact occur among the people of Ceylon at that time. Although detailed instructions were given regarding the diagnosis, preparation of drugs, and treatment of disease at that time, preventive measures for the benefit of the community do not appear to have been taken.

The Contagious Diseases Ordinance, enacted in 1867, sought to limit the ravages of venereal disease by the registration and periodical examination of women openly carrying on prostitution. According to the Medical Administration Report of 1878, this is the earliest record available in this regard.

Venereal Disease Commission

Venereal disease control on an organized basis was started in Ceylon in August, 1921, following the recommendations of a Venereal Disease Commission appointed by Mr (later Sir) Winston Churchill, which had arrived in the island in May, 1920. After touring the country and meeting various sections of the people, a Ceylon National Council was established for combating venereal disease, affiliated to its counterpart in England[12,13].

Yaws

One ofthemost commonandmostimportant skin diseasesin the pastin Sri Lanka wasyaws,or parangi, which is believedtohavebeenintroducedintothe country by the Portuguese in the 16th century. They and, later, the Dutch were accompanied by a large number of Negro slaves from Africa who probably introduced yaws as well as syphilis to the country[14]. The disease,which is referred to in an Ayurveda book in SriLanka as early as 1548, became endemic in the country, spreading untold sufferingamong theimpoverished,drought-stricken people of the dry zone.

The cause of yaws was then unknown. It was Aldo Castellani, working in Sri Lanka, who detected the spirochete responsible for the condition and named itSpirochaetapertenuis.Therewasno known treatment forthisskin diseaseuntilCastellaniintroducedaniodine mixture that,whileimproving thecondition, but failed to cure it. He used it in Sri Lanka until Ehlrich sent him his newly discovered salvarsan.

Yaws caused much concern to the health authorities then. Several special hospitals for yaws were established in remote areas and yaws clinics were conducted in some of the larger hospitals.Withtheadventofantibiotic - penicillinandits recognitionasacureforyaws,thepicturechanged completely.The disease was almost completely eradicated in the early 1950s[13].

History of Elephantiasis control in Ceylon

Perhaps the earliest reference to the condition is in SaddharmaRatanavaliya, a collection of Buddhist stories in prose, written in the 13th century A.D.by a Buddhist monk. This book is replete with similes, and the reference to elephantiasis occurs in several of them:an example is where doing something inappropriate is compared with applying medicine on the neck when the elephantiasis is in the leg.

Thefirstdefinitiveobservation wasmadebyDavy, who referred to the condition aselephantiasis or Cochin leg[15] wasvery common in the city of Cochin in South India.Davy [15] noticedthatelephantiasiswascommonalongthe SouthwesterncoastlineofCeylon,particularlyinthe townofGalle,hencethesynonymGallelegusedby both Marshall[16] and Castellani[9]. With the introduction of diethyl carbamazine in the treatment of filariasis, it is much controlled medical condition in present Sri Lanka.

Post graduate training of dermatology in Sri Lanka

Though Dermatology was a subject in the Medical school, a Consultant in Dermatology was not appointed by the Ministry of Health, Sri Lanka until 1953. In the early 1940’s to 1950’s post graduate training was mainly in the United Kingdom (UK).The first dermatologists had their training and the MRCP from the UK. Later, in the 1950’s when a dermatology department actually functioned at the General Hospital Colombo, a part of the training was serving as a house officer to this department. The trainee then proceeded to UK, obtained the diploma of the MRCP (UK), and hopefully had an adequate training in dermatology department. On return to Sri Lanka they were forthwith considered consultants in dermatology. Several decades the number of doctors that specialized as dermatologists remained small. Even in early eighties there were less than 10 dermatologists belong to the state health sector,along with the few specialists who practiced dermatology in the private sector to provide services for a population of 18 million. In 1986 at the inaugural academic session of the Sri Lanka association of dermatologists, a Sri Lankan Dermatologist was described as a “man in a million”[17].

The next phase in the post graduate education in dermatology was the establishment and activation of the Post Graduate Institute of Medicine (PGIM) of the University of Colombo in 1979.This institute, which was from then responsible for post graduate education in medicine in Sri Lanka, established boards of study in the various disciplines to guide and control education in that field. From 1979-1995 Dermatology was under the Board of Study (BOS) in Medicine. It was in 1995 that a separate BOS was established for Dermatology. A new training programme leading to Board Certification as specialists in Dermatology commenced in 2000. This new module consist of a preliminary entrance examination in basic sciences and medicine, a period of in service training and the final examination in general medicine and dermatology. After successful completion of MD in Dermatology it’s compulsory to have in service period of supervised training in a recognized dermatology department in Sri Lanka for one year and then training for further year in a dermatology department outside Sri Lanka, recognized as suitable by the board of study[18,19].

Sri Lanka College of Dermatologists

The Sri Lanka College of Dermatologists (SLCD) founded in 2005 started as the Sri Lanka Association of Dermatologists (SLAD). The SLAD was founded in 1985 when there were only 15 dermatologists in Sri Lanka. To start an academic association was the brain child of the Late Dr. WDHPerera. The main vision of such unity was to advance knowledge, promote research and communication between the dermatologists nationally and internationally.In keeping with the vision, the first annual academic session was held in 1986 in collaboration with the German Dermatological Society. Since 1991 academic sessions were held annually.

A number of international conferences were held in collaboration with dermatologists from all over the world. Links were established with International League of Dermatological Societies (ILDS) as well. In 1999 Sri Lanka joined the South Asian Regional Association of Dermatologists (SARAD) as a founder member. Sri Lanka hosted the SARAD conference in October 2003 and 2013.

The ties with the German Society of Dermatology (GDS) stand out in this respect and in year 2006 GDS donated funds for establishment of an Academic unit with a Chair in Dermatology in a university, which was established at the Faculty of Medical sciences, University of Sri Jayewardenepura.The SLAD was officially converted to a College in May 2005 and the event was celebrated at the Annual Academic Sessions of March 2006.

The first Paediatric Dermatology unit for the country was opened in 2001, at the Lady RidgewayHospital, Colombo.

There are many skin diseases which deserve formation of patient support groups. The psoriasisfoundation initiated by late Dr. WDHPerera was the first example

References

2021 Copyright OAT. All rights reserv

- Uragoda CG (1987)A History Of Medicine In Sri Lanka: From The Earliest Times - 1948 Colombo: SLMA.

- Douglas B (1999) Mahavamsa,The Great Chronicle of Sri Lanka, Modern Text and Historical Comments, Douglas Bullis.

- Uragoda CG (1984)Some historical aspects of dermatology in Sri Lanka.Int JDermatol23:78-80.[Crossref]

- Uragoda CG (1977)Medical references in ancient inscriptions of Sri Ceylon Lanka. Ceylon Med J 22: 3.[Crossref]

- Uragoda CC (1975)Medical gleanings from the Mahavarnsa. Ceylon Med J 20:19.

- Cunawardana RALH (1978)Immersion as therapy.Sri Lanka J Humanities 4:35.

- Pieris PE (1950)Sinhale and the Patriots, 1815-1818.Colombo, The Colombo Apothecaries Co Ltd,.

- Uragoda CG (1971)Sir Aldo Castellani. J Colombo Gen Hosp 2:39.

- Castellani A (1968)Microbes. Men and Monarchs, a Doctor’s Life in many Lands, London, Victor Gollancz Ltd.

- Birch CA (1974) Castellani'spaint: Sir Aldo Castellani 1877-1971.Practitioner 212:895. [Crossref]

- C De FW Goonaratna (1971)Some historical aspects of Leprosy in Ceylon during the Dutch period 1658–1796. Medical History15: 68-78. [Crossref]

- De Silva WA (1913) J Ceylon Brch R AsiatSoc 23: 34.

- Pereira EDC, Rarhnathunga CS (1965) History of venereal disease control in Ceylon. Brit J vener Dis41: 97.[Crossref]

- Kynsey WR (1881) Report on the parangi disease in Ceylon.Sessional Paper 8, Colombo, Government Printer.

- Davy J (1821) An Account of the Interior of Ceylon and of its Inhabitants with Travels in that Island. Reprint, Dehiwela, Tiara Prakasakayo, 1969.

- Marshall H (1821) Notes on the Medical Topography of the Interior of 1981Ceylon.London, Adam Black, 1821.

- Perera MSA (2008) History of Sri Lanka Association of Dermatology, Sri Lanka Journal ofDermatology 12.

- Sirimanna GMP (2010) Changing role of the Sri Lankan Dermatologist, Sri Lanka Journal ofDermatology 14.

- Prospectus Doctor of Medicine (MD) and board certification in Dermatology, Post graduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo;2014.