Abstract

Background: Demographic, professional, and emotional symptoms have been associated with higher risk for burnout reaction among health professionals. The current study focused on three groups of military health professionals: physicians, dentists, and mental health officers. The aims of this study included examining burnout indices characterizing three health professional groups, seeking associations between mental burnout subscales (job demands and social support), and testing the mediating impact of job demands and social support on burnout indices of military health professionals

Methods: A cross-sectional study design was conducted with 166 military health professionals. Respondents completed Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), which examines emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and personal accomplishment, the Job Demands Questionnaire, Multidimensional Perceived Social Support (MPSS), and a demographic questionnaire.

Results: Women, in comparison with men, reported greater social support and reported being significantly more assisted by others. Married participants and participants in a relationship, in comparison with singles, reported receiving greater support. Physicians reported higher levels of burnout. Burnout and job demands scales were strongly and positively correlated. Finally, using structural equation modeling we demonstrated that social support mediated the links between gender and family status on job demands.

Conclusions: Therapeutic and supportive resources, such as professional supervision and peer group support should be offered to physicians, who are at particular risk for burnout response. Future studies should examine other health professionals in the army, such as nurses and paramedics, to better understand their responses to stress-related situations.

Key words

mental burnout, job demands, social support, mental health officers, military physician, military dentists

Introduction

The current study examined the burnout phenomenon among three groups of military health professionals: physicians, dentists, and mental health officers. The purpose of this study was to investigate the mediating impact of job demands and social support on the mental health indices of military health professionals.

Results from previous studies on burnout of health professionals showed that in different organizations, burnout was associated with a higher risk of physical illness [1-3] and personal, emotional, and professional dysfunctions 45 [4-5].

In the military milieu, previous findings showed that 21% of mental health providers reported elevated levels of burnout [6]. Nurses in the Turkish army reported a significant correlation between burnout and symptoms of depression, manifested as weight loss and sleep disorders [4]. An additional study showed that military orthopedic residents and staff surgeons at the U.S. Army suffered from higher rates of depersonalization and reported higher lack of personal accomplishment than did civilian physicians [7].

The effects of gender on burnout response among military health professionals has been previously studied, yielding inconsistent findings. One study, carried out with Pakistani military physicians, showed that men presented higher burnout responses than did their female colleagues [8]. However, results from a different study showed that women psychiatrists reported significantly higher levels of burnout than did their male colleagues [9]. A study of U.S. Navy healthcare personnel demonstrated that when comparing the prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among women and men who had similar deployment experiences, especially combat experience, the risk of PTSD was significantly higher among women [10]. Results from a study conducted in Israel among mental health professionals revealed no significant gender differences in stress levels [11]. The present study further examines the effects of gender on burnout responses.

Job demands have been found in the literature to be one of the main factors affecting burnout responses. Job demands comprise work overload, workplace conflicts, and vague job descriptions [12]. Military health professionals are exposed to various sources of personal and environmental stress, resulting in high distress and burnout responses. Results from a meta-analysis showed that paramedics, nurses, and physicians who participated in military operations and wars suffered rates of stress disorder similar to those of combat soldiers [13]. Furthermore, a high exposure of the medical team to fighting and life-threatening situations was positively associated with higher levels of psychological distress [14-15]. A study conducted in the Israeli army found higher levels of stress related to lower seniority in the army and service of less than four years in the current position. However, health professionals serving in a combat unit close to a war zone did not differ in psychological distress from those serving in a non-combat unit, away from a war zone [11,16].

The number of hours a professional works has also been found to be positively correlated with burnout response.8 Long working hours, attending to patients diagnosed with personality disorders, were found to increase burnout levels among mental health professionals in the US military [9,11]. A supportive working environment was found to contribute to the improvement of health professionals' caring approach toward their patients, increased levels of professional fulfillment, and their sense of success [9].

The literature highlights the importance of social support on reducing negative mental health responses [18-20]. Social support comprises three main aspects: emotional support (e.g., trust, love, and empathy), instrumental support (e.g., money or time), and non-formal support (e.g., advice and guidance) [21]. Social support was found to have a direct and mediating effect on mental health responses [22]. Studies conducted in the U.S military found that the spouse's support significantly enhanced soldiers' mental state and performance [23-24]. Similar findings were reported for professionals in the Israeli army [25]. Furthermore, marital satisfaction was examined among Russian military officers, showing that both partners were negatively influenced by stressful life events and financial hardships [26].

Conservation of resources (COR) theory [27] comprised the theoretical model for the current study. A basic assumption of COR theory is that individuals seek to obtain and maintain resources, among them objects, conditions, and personal characteristics. Burnout response may occur when the individual's resources are threatened by an actual loss, or the individual had invested substantial resources, but was not reciprocated [27-28].

According to COR theory, we postulated that health professionals with high job demands and low social support would report relatively higher levels of burnout and would experience more emotional distress.

Study objectives

(1) To examine the differences on burnout indices between three groups of health professionals in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF); (2) to seek associations between mental burnout subscales, job demands, and social support; and (3) to test the mediating impact of job demands and social support on the mental health indices of military health professionals.

Method

Study design

A cross-sectional study design was employed. Inclusion criteria were health professionals, who were military officers holding a rank ranging from First Lieutenant to Major. Participants were recruited between 2013-2015 in three conferences for health and mental health professionals. These conferences were mandatory for military medical personnel by the IDF Surgeon General. This study was approved by the IDF Institutional Review Board.

Participants

The study sample included 166 health practitioners (55% were female). The participants' age range distribution was 24-30 (28%), 30-35 (34%), and 35-40 (20%); 68% were married or cohabitated, while the remainder were singles. Economic status was reported by 47% as being above average, whereas only 7% reported their economic status to be below average.

Measures

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) [29]: This 22-item questionnaire was designed to examine the intensity of burnout. The inventory is comprised of three subscales: (1) emotional exhaustion (EE), manifested in fatigue, loss of energy, and feelings of overload (9 items); sample item: "I'm mentally drained from my work"; (2) depersonalization (DP) - manifested in negative attitudes or keeping one's distance (5 items); sample item: "To be honest, I do not particularly care what happens to some of my patients"; (3) lack of personal accomplishment (LPA) - expressed negative reactions to the therapist's own sense of success and failure (8 items); sample item: "I enjoy significant achievement in my work," Each item is presented on a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (every day): A higher the score on each of the subscales indicates a higher burnout level. A general burnout score measured by an average of all items was calculated as well. For the current study, Cronbach alpha for the general score was α =.78.

Job Demands Questionnaire (JD): This 9-item questionnaire evaluates stress deriving from work [30]. Sample items include "How often do you feel stressed due to your work schedule?" "How often do you feel overloaded from multiple tasks?" and "How often do you experience emotional overload?" Items are presented on a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always). All item ratings are averaged for the total JD score. A higher score indicates greater pressure resulting from job demands [30] for the current study, Cronbach α =.845

Multidimensional Perceived Social Support (MPSS): This 12-item questionnaire was designed to examine the individual's perceived social support [31]. The items refer to support from three sources: family members, friends, and a significant other. Items such as the following appear in the questionnaire: "My family truly tries to help me," "I can count on my friends when I have problems," "I have a close person nearby when I need one.” Items are presented on a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (do not agree at all) to 7 (very much agree). All items were averaged to determine the total social support score. A higher score is indicative of greater perceived social support. For the current study, Cronbach's coefficient alpha α =.943.

Demographic Questionnaire: A demographic questionnaire was designed for collecting data regarding background variables and socio- economic status. The questionnaire was designed for this study and included items such as gender, age, country of birth (Israel or other), military seniority (less or greater than four years in the army), time at currant military job (less or greater than two years in the military job), rank (soldiers above major), degree of religious observance (secular/other), marital status (married /other), socioeconomic status (above average, average, or low), military combat (combat or non-combat units), and treating personnel (treating or not treating soldiers).

Statistical analysis

In the first stage, we compared demographic variables for the three health professional groups. In the second stage, psychological scale differences were calculated, according to demographic groups. In the third stage, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between the dependent variables, mental burnout, job demands, and social support for each of the three examined health professions. In the fourth stage, variables found to be significant in the univariate analysis were entered into a general SEM model.

Results

Comparison of demographic variables by the three health professional groups is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic variables by three health professions.

| |

|

Physicians |

Mental health providers |

Dentists |

X2 test |

|

Age |

25-30 |

25% |

42% |

43% |

X2(8)=14.17 p =.08 |

30-35 |

34% |

15% |

36% |

35-40 |

21% |

23% |

14% |

40-45 |

8% |

12% |

7% |

above 45 |

11% |

8% |

|

Family status |

Single |

30% |

36% |

29% |

X2(2)=0.75 p =.68 |

Married/ with partner |

70% |

64% |

71% |

Gender |

Male |

31% |

64% |

45% |

X2(2)=13.48

p = .01

|

Female |

69% |

36% |

55% |

SES |

Average or below |

92% |

96% |

86% |

X2(2)=3.35

p = .19 |

Above average |

8% |

4% |

14% |

From Table 1, we can see that among the three health professions, women were of highest prominence in the mental health provider group, X2(df=2)=13.48, p < .05.

In the second stage of analysis, differences between demographic variables and all the psychological scales were calculated. Burnout subscale EE distinguished between the health professions: the highest EE scores (M=3.05, SD=1.10) were observed among physicians, whereas the lowest were observed among mental health professionals (M=2.65, SD=0.80; F (2,163) =4.11 p < .05). EE was also affected by age group, with the highest EE levels found for the 35-40 age group (M=3.04, SD=0.08), with the lowest EE found in the 45+ age group (M=2.14 SD=1.04; F (4,160) =10.98 p < .05).

Job demand levels also varied by health profession, with the highest JD level among physicians (M=4.21, SD=1.10), and the lowest among mental health providers (M=3.55, SD=0.91; F (2,163)=7.28; p < .05).

Differences in perceived social support were observed by gender, with women reporting higher levels than did men (M=6.19, SD=0.95 vs. M=5.81, SD=1.01, respectively; t (164) =2.53; p < .05). Perceived social support was associated with family status, in that married or cohabitating participants reported higher levels of social support than did singles (M=6.2 SD=0.9 vs M=5.7 SD=1.4, respectively; t(164)=2.45; p< .05). Perceived social support also differed by economic status: participants with above average SES reported higher levels of perceived social support than did those with below average SES (M=6.20 SD=0.81 vs. M=5.80, SD=1.16, respectively; t(164)=2.26; p < .05).

In the third stage, Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for each of the health professions, between the dependent variables, mental burnout subscales (EE, DP, LPA), job demands (JD), and perceived social support. Table 2 presents only the significant correlations for each of the three health profession groups.

Table 2. Pearson correlations between health professions.

| |

|

Job Demands |

Social support |

EE |

Mental health providers |

.643** |

|

Physicians |

.860** |

|

Dentists |

.528** |

-.433** |

LPA |

Mental health providers |

|

|

Physicians |

|

|

Dentists |

|

|

DP |

Mental health providers |

.392** |

|

Practitioner |

.620** |

|

Dentists |

.460** |

-.420** |

Note. *p ≤ .05; **p ≤ .01

As can be seen in Table 2, burnout subscales and job demands were strongly and positively correlated among all three groups of health professionals. Only among dentists was social support negatively correlated with DP and EE (p ≤ .01)

In the fourth stage, variables that were found to be significant in the univariate analysis were entered to a general SEM model. Gender, family status, type of profession, and economic status were independent variables. We assumed that the effect of the three subscales of burnout would be mediated firstly by social support and then by job demand.

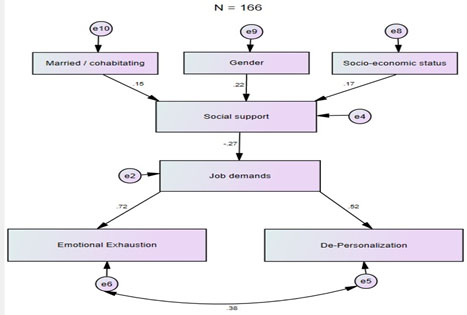

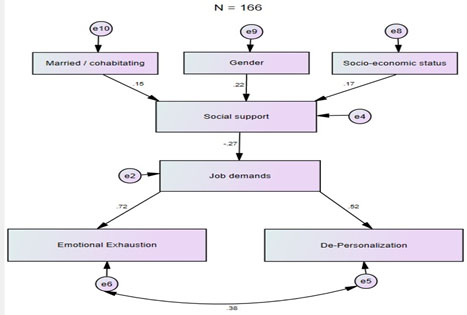

A general model in presented in Figure 1: All regression weights that appear in the figure are significant at p ≤ .05.

Figure 1. General model.

The general model, based on 166 health professionals (Figure 1), revealed a very good fit, χ2(14)=21.02, p=0.1, χ2/df=1.51, SRMR=0.050, RMSEA=0.050, CFI=0.969, and presented several direct pathways by which EE and DP were predicted. The general model addresses 51% of EE and 27% of DP variances. Economic status (β=0.35, p ≤ .05), gender (β=0.45, p ≤ .05), and living with a partner (β=0.32, p ≤ .05) were related to higher perceived social support. In summary, having an above average economic status, being a woman, and living with a partner predicted higher social support. Social support was mediated by job demands (β=–0.26, p ≤ .05), and job demands in turn affected the dependent variables, EE (β=0.68, p ≤ .001) and DP (β=0.40, p ≤ .001).

Three-group model

Following the univariate analysis that showed differences among the investigated health professionals on the psychological variables (Table 2), we examined the general model within the three groups. The three-group model showed a good fit (χ2 (42)=57.54, p = 06, χ2/df=1.37, SRMR=0.12, RMSEA=0.05, CFI=0.93). To further improve the model fit, we examined whether the magnitudes of the paths in all three groups were equivalent. This was assessed by developing a model that constrained the paths between the demographic variables and social support. While constraining all the demographic paths to be equal between all three groups, the model achieved a very good fit (χ2 (48)=58.35, p=0.15, χ2/df=1.22, SRMR=0.12, RMSEA=0.04, CFI=0.9(. Thus, it was concluded that the three paths are equivalent in the three groups. However, constraining all other paths yielded a non-appropriate model fi (χ2 (48)=71.46, p ≤ .05, χ2/df=1.49, SRMR=0. 14 RMSEA=0.055, CFI=0.89). In other words, only the demographical path on social support could be constrained between the three groups.

Table 3 illustrates differences of paths magnitudes. There were substantial differences of the standardized regression weights between the three health professional groups with respect to the effects of social support on job demands, job demands on EE, and job demands on DP.

Table 3. Difference in standardized regression weights between the three health professional groups* *.

| |

|

Mental health providers |

Physicians |

Dentists |

Social support |

Job demands |

-0.112 |

-0.206 |

-0.536 |

Job demands |

Emotional exhaustion |

0.643 |

0.86 |

0.527 |

Job demands |

Depersonalization |

0.392 |

0.62 |

0.464 |

High socioeconomic status |

Social support |

0.193 |

0.174 |

0.167 |

Married/cohabitating |

Social support |

0.139 |

0.141 |

0.12 |

Gender |

Social support |

0.19 |

0.192 |

0.179 |

Note. *All beta coefficients reached .05 level of significance.

Table 3 and Figure 1 demonstrate that perceived social support mediated the effect of demographic variables on job demands, mainly among dentists. Job demands mediated the social support effect on emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, with the highest mediation effect apparent among physicians.

Discussion

The current study examined the burnout response of army health professionals. We measured demographic, psychological, and professional factors and examined their impact on their burnout responses. Participants consisted of 166 health professionals-physicians (26%), mental health officers (47%), and dentists (25%).

Among our respondents, self-reported burnout and job demands scales were strongly and positively associated. Previous studies showed that high job demands were related to medium-to-high burnout levels among military health professionals [3,12,17]. A possible explanation for this link is that the health professional in the army holds a dual role: they serve as a military commanding officer and also function as a health professional [15].

Social support has been recognized in the literature as a protective factor to alleviate distress [19]. Our findings showed that women, to a greater extent than men, reported higher levels of social support and reported receiving significantly greater assistance from others. These findings corroborated previous findings examining gender differences among health professionals [25]. We also found that married participants and participants in a relationship, relative to singles, reported greater social support and familial support. Studies conducted in the US army and in the IDF among families of professional officers showed that the soldier's mood and quality of task performance were affected by the spouse's emotional support [23-25]. Another finding of the current study was that participants with above average economic status, compared with those of low economic status, reported greater social support. This finding corroborated results from previous studies showing that multiple social-economic resources were related to a decrease in burnout responses [32].

Social support has been reported as a resource that moderated stressful events [33]. Results from another study showed that social support directly reduced negative mental health symptoms [34]. Our results showed that social support mediated the links between demographic factors, gender, and family status on job demands. According to COR theory, social support provides psychological and materialistic resources that contribute to one's ability to better adapt to a variety of stressful situations. The absence of social support may decrease one's ability to face job demands, thus leading to lower mental health functioning [27].

This is the first study, to the best of our knowledge that has examined the burnout response of military physicians, mental health professionals, and dentists, using SEM analysis. SEM has several advantages over descriptive or multivariable regression analysis. It controls for measurement error, and most importantly allows for the simultaneous evaluation of all study variables and possible pathways. Our final model was determined by adding pathways based on AMOS modification indices, presenting those pathways offering the best statistical fit. Thus, our final model provides the most exact statement of the interactions of the variables, and as such, improves on the reported correlations. The path analysis showed that job demands mediated the links between social support and burnout reactions. Social support had a negative direct impact on job demands, whereas the latter was positively linked to burnout processes. A previous study showed that a demanding job and peer support were correlated significantly with all aspects of burnout among nurses [35]. Results from another study using the SEM model suggested that job demands and emotional burden at work predicted nurses' well-being and reduced burnout [36]. An additional nurse's study indicated that social support moderated the impact of work demands on personal accomplishment [37].

Specific differences were observed among the three groups of health professionals participating in the current study: job demands' mean values were highest among physicians and lowest among mental health officers. A possible explanation for our findings can be derived from the relatively high rates of physicians who served in combat units, compared with mental health professionals. It may be that the dual role of the physician's work is portrayed in his combat role along with combat soldiers in military operations, while at the same time caring for wounded soldiers. Dentists and mental health officers do not participate in combat in the IDF and are thus less exposed to life-threatening situations. Our findings also pointed to distinct burnout reactions of the three health professionals: emotional exhaustion mean values were highest among physicians, whereas mental health officers reported lower levels of burnout. Social support mediated the effect of demographic variables on job demands, primarily among dentists.

Previous studies conducted with military health professionals have yielded conflicting results. In a Turkish study, distress reactions of military health professionals, physicians, nurses, dentists, lab technicians, and social workers were compared. All professionals served in disaster areas, yet more nurses developed post-traumatic disorders, compared with other professionals [38]. However, results of a meta-analysis on medical teams who participated in military operations and in wars, found that all professionals suffered from stress disorders to a similar extent as did combat soldiers. A longer exposure to life-threatening situations was linked to higher psychological distress.13

The current study has several limitations that should be noted. The research population was comprised of health professional officers, who may have been reluctant to express and expose their own mental situation, despite the anonymity of the questionnaire. A further limitation is the subjective nature of the measures employed in the current study. No objective measures, such as bio-medical data, were included. Future studies should consider integrating bio-medical and psychological measures to better understand the psychophysical ramifications of burnout processes. Despite these limitations, we demonstrated for the first time that above average economic status, being a woman, and living with a partner predicted higher perceived social support. Social support was mediated by job demands, and job demands in turn affected the dependent variables measuring burnout responses.

Our findings may have relevant implications for military policymakers. It would appear that physicians are particularly high risk for burnout responses. We thus recommend that specific therapeutic and supportive resources, such as professional supervision and peer group support, be offered to physicians and other health professionals in the course of their military service. Future studies are called to monitor the effect of such interventions on health professionals' burnout responses. Future studies should also monitor other health professionals in the army, such as nurses and paramedics, to better understand their responses to stress-related situations.

Author contributions

L. Shelef, Ph.D and I. Oz had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design

All authors.

2021 Copyright OAT. All rights reserv

Acquisition of data

L. Shelef L, and I. Oz .

Analysis and interpretation of data

All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript

All authors.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

All authors.

Statistical analysis

All authors.

Conflict of interest disclosures

All authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

Indications of previous presentation

No previous presentation, nor date(s) or location of meeting.

Funding/Support

None.

References

- Leiter MP and Maslach C (2001) Burnout and health. In A. Baum, T.A. Revenson, & J. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of health psychology (pp. 415-426). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum & Associates.

- Melamed S, Shirom A, Toker S, Shapira I (2006) Burnout and risk of type 2 diabetes: A prospective study of apparently healthy employed persons. Psychosom Med 68: 863-869. [Crossref]

- Toker S, Melamed S, Berliner S, Zeltser D, Shapira I (2012) Burnout and risk of coronary heart disease: A prospective study of 8838 employees. Psychosom Med 74: 840-847. [Crossref]

- Bakir B, Ozer M, Ozean CT, Cetin M, Fedai T (2010) Klinik psikofarmakoloji bulteni. Bulletin of Clin Psychopharmacol: 160-163.

- Jayoung L, Nayoung L, Eunjoo Y, Min S (2011) Antecedents and consequences of three dimension of burnout in psychotherapists: A meta-analysis. Professional Psychol: Res Prac 42: 252-258.

- Kok BC, Herrell RK, Grossman SH, West JC, Wilk JE (2015) Prevalence of professional burnout among military mental health service providers. Psychiatric Services 67: 137-140.

- Simons BS, Foltz PA, Chalupa RL, Hylden CM, Dowd TC, et al. (2016). Burnout in US military orthopaedic residents and staff physicians. Mil Med 181: 835-839.

- Chaudhry MA, Khokhar MM, Waseem M, Alvi ZZ, ul Haq AI (2015) Prevalence and associated factors of burnout among military doctors in Pakistan. Pak Armed Forces Med J 65: 669-673.

- Ballenger-Browning KK, Schmitz KJ, Rothacker JA, Hammer PS, Webb-Murphy JA, et al. (2011) Predictors of burnout among military mental health providers. Mil Med 176: 253-260. [Crossref]

- MacGregor AJ, Clouser MC, Mayo JA, Galarneau MR (2017) Gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder among U.S. Navy healthcare personnel. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 26: 338-344. [Crossref]

- Shelef L, Rotenberg Y, Fruchter E (In press) Belief in the ability to deal with an emergency situation among IDF mental health officers - A survey conducted during a military operation.

- O’Rourke E, O’Brien,K, Kimberly E (2014) Extending conservation of resources theory: The interaction between emotional labor and interpersonal influence. Int J Stress Manag 21: 384-405.

- Gibbons SW, Hickling EJ, Watts DD (2012) Combat stressors and post-traumatic stress in deployed military healthcare professionals: An integrative review. J Adv Nurs 68: 3-21. [Crossref]

- Bride BE, Figley CR (2009) Secondary trauma and military veteran caregivers. Smith College Studies in Social Work 79: 314-329.

- Linnerooth PJ, Mrdjenovich AJ, Moore BA (2011) Professional burnout in clinical military psychologists: Recommendations before, during, and after deployment. Professional Psychol: Res Prac 42: 87-93.

- Cragun JN, April MD, Thaxton RE (2016). The impact of combat deployment on health care provider burnout in a military emergency department: A cross-sectional Professional Quality of Life Scale V survey study. Mil Med 181: 730-734.

- Lang GM, Pfister EA, Siemens MJ (2010) Nursing burnout: Cross-sectional study at a large army hospital. Mil Med 175: 435-441. [Crossref]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR (1995) The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull 117: 497. [Crossref]

- Baumeister RF, DeWall CN, Ciarocco NJ, Twenge JM (2005) Social exclusion impairs self-regulation. J Pers Soc Psychol 88: 589. [Crossref]

- DeWall CN, Baumeister RF (2006) Alone but feeling no pain: Effects of social exclusion on physical pain tolerance and pain threshold, affective forecasting, and interpersonal empathy. J Pers Soc Psychol 91: 1-15. [Crossref]

- Pinkerton J, Dolan P (2007) Family support, social capital, resilience and adolescent coping. Child & Family Social Work 12: 219-228.

- Stice E, Ragan J, Randall P (2004) Prospective relations between social support and depression: Differential direction of effects for parent and peer support? J Abnorm Psychol 113: 155 [Crossref].

- Bell DB, Stevens ML, Segal MW (1996) How to Support Families during overseas deployments: A sourcebook for service providers. Alexandria, VA: U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences.

- Wiens TW, Boss P (2006) Maintaining family resiliency before, during, and after military separation. In CA Castro, C Andrew, AB Adler, TW Britt, (Eds.) Military life: The psychology of serving in peace and combat: The military family (Vol. 3, pp. 13-38). Westport, CT: Praeger Security International.

- Eran-Jona M (2007) The" Woman of Valor" and the" New Man": Two models of the "ideal family" and their implications for gender arrangements in families of women and men who serve in the Israeli military [In Hebrew] Sotzyologyah Yisra’elit, 8(2), 209–239. Eran-Jona, M. (2011). Married to the military: Military-family relations in the Israel Defense Forces. Armed Forces & Society, 37(1), 19-41.

- Westman M, Hobfoll SE, Chen S, Davidson OB, Laski S (2005) Organizational stress through the lens of conservation of resources (COR) theory. In P. Perrewé & D. C. Ganster (Eds.), Research in occupational stress and well-being (pp. 167-220). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Hobfoll SE (2001) The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychol: An Int Rev 50: 337–421.

- Hobfoll SE, Vinokur AD, Pierce PF, Lewandowski-Romps L (2012) The combined stress of family life, work, and war in Air Force men and women: A test of conservation of resources theory. Int J Stress Manag 19: 217.

- Maslach C and Jackson S (1993) Maslach Burnout Inventory manual. Firenze: Organizzazioni Speciali.

- Kanner A, Kafry D, Pines A (1978) Conspicuous in its absence: The lack of positive conditions as a source of stress. J Hum Stress 4: 33-39.

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK (1988) The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Personal Assess: 52: 30-41.

- Hakanen JJ, Bakker AB, Jokisaari M (2011) A 35-year follow-up study on burnout among Finnish employees. J Occup Health Psychol 16: 345. [Crossref].

- Williams KD (2007) Ostracism. Psychol 58: 425- 452.

- Toker S, Shirom A, Shapira I, Berliner S, Melamed S (2005). The association between burnout, depression, anxiety, and inflammation biomarkers: C-reactive protein and fibrinogen in men and women. J Occup Health Psychol 10: 344 [Crossref].

- Fong CM (2016) Role overload, social support, and burnout among nursing educators. J Nurs Educ 29: 102-108 [Crossref].

- Chou HY, Hecker R, Martin A (2012) Predicting nurses’ well-being from job demands and resources: a cross-sectional study of emotional labour. J Nurs Manag 20: 502-511 [Crossref].

- Devereux JM, Hastings RP, Noone SJ, Firth A, Totsika V (2009) Social support and coping as mediators or moderators of the impact of work stressors on burnout in intellectual disability support staff. Res Dev Disabil 30: 367-377 [Crossref].

- Akbayrak N, Oflaz F, Aslan O, Ozcan CT (2005) Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among military health professionals in Turkey. Mil Med 170: 125 [Crossref].