This paper analyses the origins and evolution of harm reduction measures like Opioid Substitution Therapy (OST) and Needle/syringe exchange programmes (NSPs), in Spanish prisons. The information was taken from reports, bulletins, specifications, central records and other documents containing health information related to this issue from 1997 to 2017.

prison, drug users, public health practice, substance abuse treatment centres, HIV infections, communicable diseases

Nowadays, the HIV/AIDS infection still represents an important challenge worldwide. In the past years, Spain has been at the head of the incidence and prevalence rates in Europe. But without a doubt, the most important problem has been in penitentiary centres, where the mean incidence and prevalence rates go clearly beyond those of the community populations, in Spanish prisons HIV infection among prisoners was reaching 30% in 1990 [1]. This was one of the main reasons because Spain was one of the countries which first and more broadly implemented harm reduction programs (opioid substitution therapies and syringe exchange programs) in response to the epidemics of transmitted diseases related to IV drug use.

Key points for implementing harm reduction programs in prisons in Spain

In the late 80s the imprisoned population in Spain assembled a series of risk factors involving one of the highest HIV or viral hepatitis infection rates in Europe [2] 46% of inmates were people who inject drugs (PWID) and sharing needles. Drug use under unhygienic conditions, and above all, the sharing of injection material between inmates, entails a high risk regarding the transmission of infections such as hepatitis, HIV, abscesses, yeast infections, etc.

Some facts must be enfaced in these context

Evaluation based on scientific evidence, have proved harm reduction measures efficacy in the community [3]. In 1993, the World Health Organization and the Council of Europe, invited those countries to consider their implementation in prisons of harm reduction programs where Needle Exchange Programs (NEPs) which were being developed within the community [4].

The impaired access to sterile needles and syringes in a closed environment such as prisons, entails that these are reused many times and shared between different inmates. If we also take into account the high prevalence of HIV and hepatitis, as well as drug use under unhygienic conditions, we will encounter a high risk for the transmission of infections.

The remarkable challenge that facing this situation meant empowered the prison health administration in Spain, with a valuable collaboration from the Public Health Authorities form Ministry of Health, to undertake efficient and advanced measures based on the following premises: availability of antibody voluntary detection tests for all prisoners, confidentiality of results, no segregation upon results, free distribution of condoms and lubricant, access to harm reduction programs, health related education and information about HIV/AIDS and other infectious agents in prison through health mediators trained among prisoners, access to similar therapeutic alternatives as those provided outside prison and entitlement to parole for prisoners suffering from a terminal illness when the vigilance judge considers it appropriate.

These measures were based on the fact that coercive interventions at that moment were counterproductive for the control of the transmission of infectious diseases and their consequences in prison and then we need to change the strategy, lean on personal responsibility of PWID. Therefore, this kind of efforts, developed in the extra penitentiary context, were frequently criminalized especially in penitentiary context, even though their benefits (reduction of the transmission of HIV, hepatitis A, B and C and reduction of overdoses) [5].

Prisons can’t be considered as an isolated element within the society. Meanwhile the coverage of their needs must be ensured, especially concerning their right to health. We must not forget that prisons represent the first assistance resource for that part of the society that gains access to the public assistance system with difficulty, partly because of the social exclusion that a great deal of prisoners present upon imprisonment, and partly due to self-exclusion representative of groups with a separate subculture, on the threshold of illegality. Health protection in prisons is an essential part of public health [6], improving inmates health we help to improve the health of the communities from which they come and to which the will return once they have served their sentence.

Steps in the implementation of harm reduction programs in Spanish prisons

The first prevention and control program regarding communicable diseases was implemented in 1990, basically are aimed at early detection of the cases, monitoring and appropriate treatment, along with preventing new cases of HIV, hepatitis B and C and tuberculosis, including the distribution of bleach. This first program did not consider the distribution of needles, nor substitutive therapy for opiate addiction (OST) [7].

In 1992, two years later, efficacy-proved measure outside prison, Opioid Substitution Therapies (OST), was undertaken: Methadone Maintenance Program (MMP) was launched at the same time that a Health Education Program (HEP), were inmates act as health agents. These two programmes working together, became one of the main tools in rescuing inmates from harm reduction programs and transferring them to rehabilitation program which will enable their best social reintegration. While, the provision of sterile injection material for their use in prisons would have to wait another 5 years because had not yet undergone what someone called a “legality test” [8].

In nineties in Spain over 50% of the people who went to prison report a history of drug use, and almost half of them by means of IV injection. Despite the measures adopted by the institutions to try and stop drugs getting in prison, along with the extension of drug addiction care services to all prisons, many PWID manage to go on consuming on the inside prisons, no matter if they could enter in different programmes ranging from drug-free to Opiate Substitution Treatments (OST). The high number of PWID among inmates, together with the high prevalence of HIV and HCV and the verification that OST has proven insufficient to avoid the sharing of injection material, implied the need to take a step further in harm reduction measures. In a closed medium like prisons, the lack of access to sterile needles and syringes increases the probability of their being re-used and shared. In these circumstances the hepatitis viruses and HIV find the way paved for easy propagation.

The remarkable challenge that facing this situation meant empowered the prison health administration, with the collaboration of the Spanish Ministry of Health, to undertake efficient and advanced measures in the community with remarkable success as far as prevention and health promotion are concerned. Several studies have concluded that Needles Exchange Programmes (NEPs), are efficient in modifying high risk practices directly related to intravenous drug use, and therefore, are efficient in reducing the risk of infection transmission [9–13]. Moreover, OST contributes indirectly to harm reduction by increasing access to care and encouraging better compliance [14]. Some pilot NEPs had proven success in prisons [15].

The first NEP pilot program in Spain was launched in July 1997 in Bilbao prison [16], and later in 1998 in Pamplona prison [17], then in 1999 in Tenerife and Orense. An evaluation of results was done In April 2000 [18], results leave no doubt as to their feasibility and effectiveness, without any impairment of prison security. In 2003, Secretariat of Spanish Prisons launched the definitive Frame Work Program of NEP for Spanish Prisons, with the aim to disseminate this actuation through all prison system in Spain.

Requirements to implementing harm reduction programs in the Spanish prison system

From all of these kinds of programs probably the NEPs is one of the most difficult to implement in prison environments, because this, I will describe only the process done in the Spanish prisons system to implementing this specific Harm Reduction program.

Requirements to implement the NEP in prison

A big public health problem to resolve

Facing high rates of important transmitted diseases like infection by HIV, HC viruses associated with drug injection in the IDU prison population by means of the shared use of needles and syringes. What was happening in Spain when the program started? [19]

- In general population, on IDUs we find a 30-54% prevalence of HIV infection and much higher of hepatitis C.

- The percentage of cases of AIDS in IDUs declared to the National Register of Cases exceeds 60%.

- Over 25% of the people into prison were reporting a history of IV drug use.

- In the late eighties and early nineties, about one out of three inmates were infected by HIV.

Special conditions arise in the prison environment that propitiate the spread of infections among injecting drug users: high prevalence of HIV, HBV and HCV, limited access to sterile injection material, and high probability of repeated and shared use of the scarce material available. Harm reduction programmes for drug users aim to minimise the adverse effects for individual and collective health in prison.

Team requirements

Cooperation and coordination, not only between the prison staff but also with other institutions, are essential for the proper development of the NEP. The support of the prison authorities and cooperation of the officers are key factors for the success of the programme [16]. It was of paramount importance to know the opinion of prison staff, especially of those implied in surveillance duties, who are those more directly affected by the NEP and whose cooperation is essential for the implementation and development of the program [20]. Even it is important to know the inmate’s opinions. Before the program starts in Spanish prisons some questionnaires were passed to prison staff and prisoners [14,21,22]. At least during the first months the programme is in operation it is also important to give specific information on the NEP to the prison warders. Once the programme is firmly established, it is wise to keep them informed through meetings, ongoing training courses or other means. Before starting the programme, both the inmates and the prison staff should be informed on an individual basis and in small groups. Subsequent to its start-up, updated information should be given on it at the times considered necessary.

The vast majority of inmates said that drug use was very common in prison, extending to more than 50% of prisoners in their opinion, but they perceived intravenous drug use was less than 15%. 73% of inmates agreed with the improvement of a needle exchange program in prisons. 43.4% said that drug use will increase substantially or quite a lot whit the NEP. The opinion of 74.7% of prisoners was that the most suitable place for exchanging needles was the health care office. Most inmates (81.4%) agree that the prison health team was who should do the needle exchange. 70.1% of inmates are in strong agreement with the confidentiality of in the program [20].

On the other hand, a vast majority officers surveyed, before launching the NEP, (77%) were aware of the health problem that sharing injection material between IDUs implied. The lack of information about the programme and its rules of operation could be one of the reasons for this because the majority of officers (64%) don’t agree with the implementation of NEP. Officers (55.5%) thought that NEP would cause demotivation in the control of prison drug use among security staff and would decrease the rigour of searches. Officers were worry because NEP could increase the risk of accidental transmission to officers in inmate searches. 66.9% said that this risk will increase notably [19].

Throughout ten years of NEP implantation in prison, officers have not recognized any improved conflict nor an increased intravenous drug use, and most of them believe that the NEP improves hygienic conditions for inmates. By the end, almost 50% of officers reported that their opinion was more favourable now than at baseline, when the program begins, and only 3.8% report a worsened opinion [19]. Only the normal development of the program throughout these years, together with the cooperation of officers, has turned an initial unfavourable opinion towards the implementation of a NEP into a more favourable one and it has entailed its standardization.

The opinion of inmates was also gathered independently of whether they were NEP users or not. Most of the inmates who answer to the self-filled survey believe that the NEP has not increased the consumption of intravenous drugs, yet a significant 37.5% believe that it fairly or very much does so, in comparison of 17.1% of officers who think similarly. Over 75% of inmates believe that the NEP has significantly reduced the sharing of injection material and almost 85% believe that hygienic conditions have been improved for IDUs in prison. It is relevant to underline the acceptance of the NEP by both drug users and non-users [19]. As far as NEP users are concerned, far from increasing the frequency of intravenous drug abuse, this has progressively been reduced and years later 60% of users report intravenous drug use less than once every week. Ten years after the implementation of the NEP, 81.8% of users deny having shared injection material in the last 6 months while only 54.2% did so in the initial survey [19].

Legal requirements

Spanish prison legislation does not refer anywhere specifically to syringes or other instruments used for drug administration. The ban on needles and syringes is controlled by internal rules drawn up by the Board of Directors of each institution and approved by the Directorate General for Prisons.

Before starting the programme, it is essential to amend the internal rules and specifically permit possession of syringes under the conditions set forth in the programme. The possession and consumption of toxic substances and/or narcotics will continue to be forbidden, in as much as they are governed by the Prison Act (art. 22) and the Prison Regulations (art. 51), while possession remains a serious offence.

Results of harm reduction programs in Spanish prison system

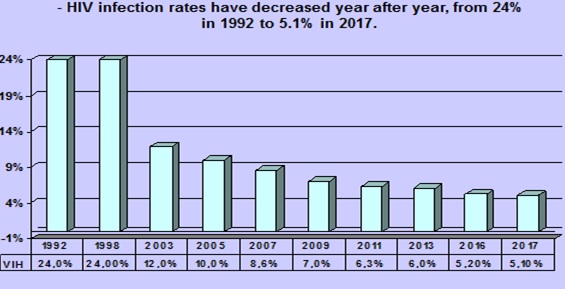

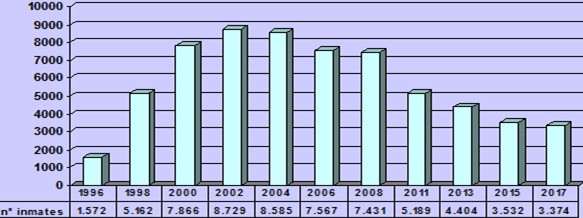

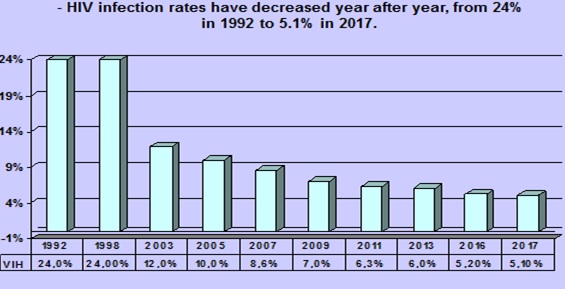

The prevalence of HIV in prison population, which is obtained by two transversal studies carried out in mid-June and mid-November every year and which include information about all prisoners at the time [23], has followed a descending trend throughout the last twenty years, the prevalence in 2018 is being 4 times lower than that of 1992 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Reduction of HIV infection rates in prisoners.

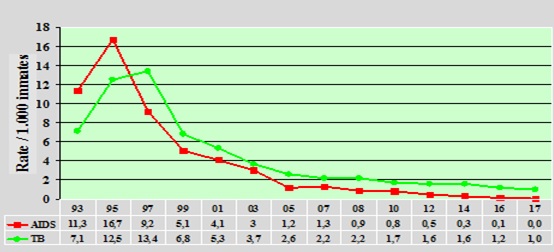

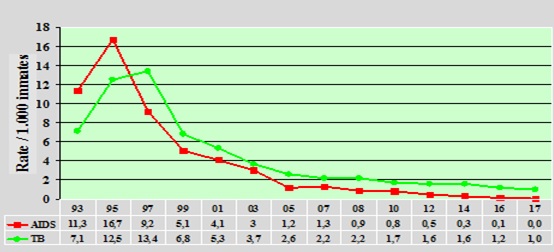

The evolution of the incidence of HIV and tuberculosis have followed a descending trend with almost parallel curves, something which shows the close relationship between both diseases. From 1994, when the number of AIDS cases hit its highest level because of the inclusion of pulmonary tuberculosis as indicative, to 2008 the number of AIDS cases has dropped by 93.7%. As far as Tuberculosis is concerned, its decrease began two years later, in 1996, and since then it fell by 85% [21] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The evolution of the incidence of AIDS and Tuberculosis in Spanish prisons.

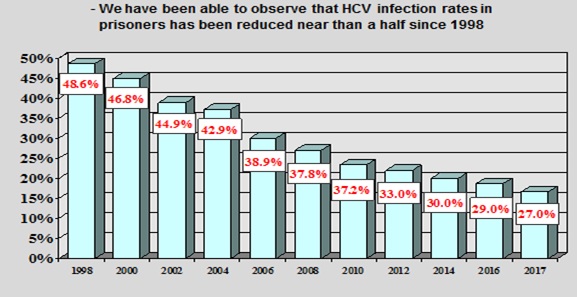

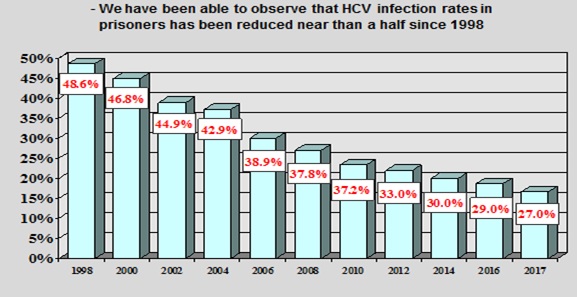

Regarding the prevalence of the infection by hepatitis C virus, which was highly prevalent in 1998, we can see how it has dropped by half throughout the last 10 years [21] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Reduction of HCV infection rates in prisoners.

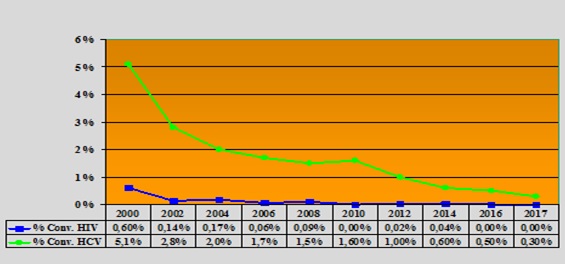

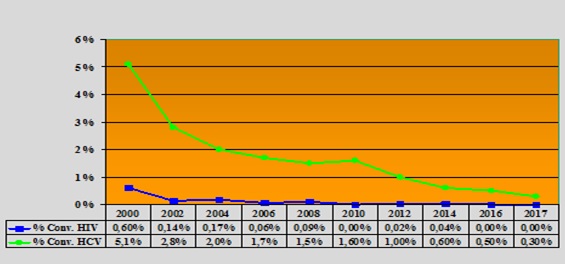

The evolution of HIV and HCV serconversion among prisoners (when transmission has taken place only inside prison), represent in a clearer way the efficiency of prevention and control programs implemented in prison. seroconversion rates regarding both infections have dropped in the last 13 years (about which data is available), by 97% regarding HIV and by 80% regarding HCV [21] (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Seroconversions to HIV and HCV inside prison have decreased dramatically since 2000, the first year which there was evidence of this data.

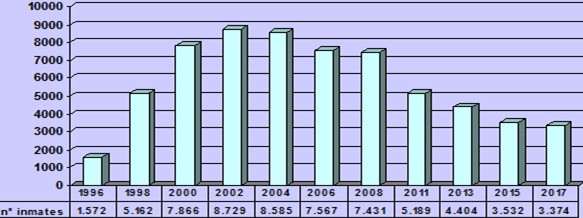

The evolution of methadone maintenance programs in prisons shows a progressive increase in the number of users since its implementation in 2003 and a slow but progressive reduction in the course of the last years, partly because of the change of habits regarding psychoactive substance abuse which are no longer mostly opium derived but stimulating substances like cocaine, and partly because the number of drug addicts among inmates has proportionally decreased (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Prisoners in Methadone maintenance programme in Spanish prisons.

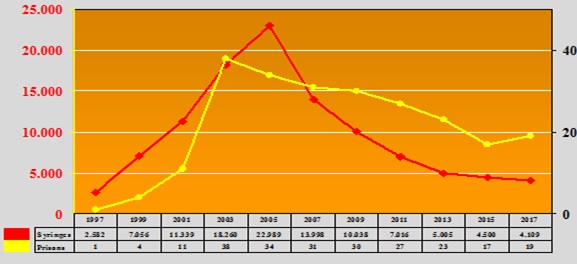

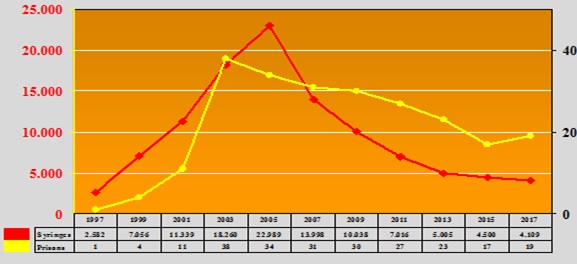

Regarding the number of prisons with needle exchange programs as well as the total number of needles provided, the curve shows three different zones: one representing the first years after implementation, with a slow beginning, a second one with an exponential increase in the number of facilities which implement the program after the publication of the order that compelled all prisons to do so, and a third one representing the maintenance of the number of prisons in the last years. The number of needles provided progressively increased until 2005 when it slowly started to fall. In the last years we have observed a reduction of the number of users of harm reduction programs which is partially due to the modification of consumption habits and the proportional reduction of drug users among prisoners. The implementation of health education programs and the preparation of mediator programs, which directly include prisoners as active health agents, also have been efficient in improving habits among prisoners, reducing injecting drug use and sharing needles [21] (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Number of prisons with needle Exchange programs in Spanish penitentiary system and number of needles provided.

A set of escalate measures

As part of the Public Healthcare Service, Prison Health must ensure equivalent assistance to the one provided outside prison. In response to WHO criteria, a series of activities were set in motion in the 90s by prisons in Spain, which focused on improving the situation of the inmates, including illness prevention and control, and harm reduction and health promotion programs. Each program is some part of a comprehensive response; a escalate plan of measures, beginning with prevention and education from drug free wings, and ending with harm reduction activities like NEPs in prison. Clinical assistance of infections and behavioural treatment to change unsafe habits are included as main parts of these public health programs for prisoners.

Contact with the institutions of the community, continuity of care

In 1993 the World Health Organization and the Council of Europe issued recommendations in relation to HIV/AIDS in prisons which stated expressly that "in countries where sterile needles and syringes are available for injecting drug users in the community, the possibility of providing prisoners who so request with sterile injection kits should be considered". The degree of application of this guideline has been limited everywhere on the grounds, especially in prisons, because the apparent illegality and hazard of these measures.

Because that, if you try to implement a programme of these characteristics in prison, you first must establish contact with institutions in the community with high experience in conducting Harm Reduction Programs. The aim is to coordinate efforts and explore how can you transfer this kind of programs into prison system, in order to assure the continuity of care of patients, inside and outside prison.

Health care in prison with the same quality standards

Drug users, mainly intravenous ones, are a population which, apart from the risks derived from their lifestyle, are stigmatized and discriminated by the society and are therefore, more vulnerable, presenting impaired physical and mental health in comparison to the non-drug user population. Most of them have seldom or never, accessed health care services before imprisonment and mental disorders together with drug abuse and infectious diseases are their main health issues. Prison services are compelled to ensure that its users –inmates - are provided in prison with health care with the same quality standards than those available outside prison, according to provisions established by UN and the Council of Europe in the 60s.

Prisons are the first health care resource for that part of the society which has difficult access to the public health care system, either due to marginalization or to self-exclusion. Prisons cannot be considered as an isolated element of the society, imprisoned people come from the society and they will return to it; meanwhile the must be ensured the right to the coverage of a series of needs, among which the right to health stands out.

Each society has its own view, tradition and history about the use of illicit drugs and these opinions cannot be ignored in deciding what is possible to be done in the prison system. Against an assessment of the size and nature of the problem, and with local awareness of legal, social and political factors, there are a list of actions which countries can consider, knowing that there is available considerable evidence of effectiveness and which have the backing of the key international organisations who are expert in the challenges of communicable diseases in prisons.

In the last international conference on health protection in prisons, held in Madrid in October 2009, prison health issues was selected to be the central focus of the meeting, why? The sad fact is that in every society in Europe, the greatest preponderance of serious life-threatening diseases is likely to be amongst those held in prisons and places of compulsory detention. Communicable diseases such as HIV and Tuberculosis, addictions to various substances and drugs and mental health illnesses and inadequacies, either together or on their own, affect the vast majority of the prison population in every country of Europe and beyond. In the Conference was agreed the Madrid Recommendation, a document with a quite comprehensive list of measures based on international recommendations from expert organisations such as WHO, UNODC and others, on health protection in prisons as an essential part of public health. It is a short but influential document coming with such support that it should be considered by every health department and public health agency concerned with the better control and the prevention of such important diseases as HIV and Tuberculosis.

The Madrid Recommendation maintain that there is a real public health problem in prisons as far as communicable and other diseases were concerned, and that considerable evidence had shown that much could be done in prisons to prevent the spread of these conditions and indeed to contribute to improving the health of the community. The document recognised the considerable differences of opinion which existed throughout Europe and elsewhere about what should be done. All countries will recognise the importance of the problem, will review their current position and will select from the list of effective interventions included in the Recommendation those which are suitable and acceptable to meet the needs of their country.

Health protection measures, including harm reduction, are effective

There is now evidence that health protection measures, including harm reduction measures, are effective within the settings of Spanish prisons, despite the well-known tensions between places where secure detention is a primary goal instead the basic requirements for health protection, treatment and prevention. Some facts were proved in Spanish prisons:

- The number of prisoners, who have never shared injecting material has increased.

- The percentage of individuals who said they used condoms systematically has increased significantly.

- There has been a decrease in the number of individuals who have consumed drugs, and more particularly among those HIV positive.

- The individuals with drug consumption record presented higher levels of knowledge about the HIV infection, the risk perception variable seems to be the base of this explanation.

- There has been an important decrease in HIV prevalence, infection rates have dropped year after year.

- The rest of diseases approached by these programs have followed the same lead: hepatitis has fallen, TB incidence rates is lower and as far as HIV and HCV seroconversions are regarded, they have both significantly dropped.

- Officers have not recognized any improved conflict nor an increased intravenous drug use, and most of them believe that the NEP improves hygienic conditions for inmates.

We wish to thank Prison Secretariat of Spain for the data sharing

- Secretaría General de Instituciones Penitenciarias. Ministerio del Interior Estadística Sanitaria 2016, Nacional y por centros. Indicadores de Actividad Sanitaria. Coordinación de Sanidad Penitenciaria. 2017. Madrid

- Parra F Sida y prisión. (2000) Editorial Rev Esp Sanid Penit 1: 1-2.

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. 2011. Harm reduction: evidence, impacts and challenges. Luxembourg: EMCDDA.

- Recomendación No R (93) 6 del Comité de Ministros de los estados miembros concerniendo a los aspectos penitenciarios y criminológicos del control de las enfermedades transmisibles y del SIDA en particular, así como de los problemas relacionados de salud en prisión, 1993. Consejo de Europa. Estrasburgo.

- Fazel S, Baillargeon J (2011) The health of prisoners. Lancet 377: 956-965. [Crossref]

- Madrid Recommendation. 2009 WHO Europe. Available at http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-determinants/prisons-and-health/publications/2010/the-madrid-recommendation-health-protection-in-prisons-as-an-essential-part-of-public-health.

- Martín-Sánchez M (1990) Programa de prevención y control de enfermedades transmisibles en Instituciones Penitenciarias. Revista de Estudios Penitenciarios Monográfico de Sanidad Penitenciaria. 51-67.

- Barrios-Flores LF (2003) Origen y modelos de Programa de Intercambio de Jeringuillas (PIJ) en prisión. Rev Esp Sanid Penit 5: 21-9.

- Lurie P, Reingold AL, Bowser B, Chen D, Fo- ley J, et al. (1993) The public health impact of needle exchange programs in the United States and abroad. Summary conclusions and recommendations. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Vlahov D, Junge B (1998) The role of needle exchange programs in HIV prevention. Public Health Rep 113: 75-80. [Crossref]

- Stimson GV (1989) Syringe-exchange programmes for injecting drug users. AIDS 3: 253-260. [Crossref]

- Hartgers C, Buning EC, van Santen GW, Verster AD, Coutinho RA (1989) The impact of the needle and syringe-exchange programme in Amsterdam on injecting risk behaviour. AIDS 3: 571-576. [Crossref]

- Van Den Berg C, Smit C, Van Brussel G, Coutinho R, Prins M, et al. (2007) Full participation in harm reduction programmes is associated with decreased risk for human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus: evidence from the Amsterdam Cohort Studies among drug users. Addiction 102: 1454-1462. [Crossref]

- Roux P, Carrieri MP, Villes V, Dellamonica P, Poizot-Martin I, et al. (2008) The impact of methadone or buprenorphine treatment and ongoing injection on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) adherence: evidence from the MANIF 2000 cohort study. Addiction 103: 1828-1836. [Crossref]

- Nelles J, Fuhrer A, Hirsbrunner H, Harding T (1998) Provision of syringes: the cutting edge of harm reduction in prison? BMJ 317: 270-273. [Crossref]

- Secretaría del Plan Nacional sobre SIDA (1999) Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. El programa de intercambio de jeringuillas en la prisión de Basauri: 2 años de experiencia. Madrid.

- García-Villanueva M, Huarte J, Fernández de la Hoz K (2006) Siete años del programa de intercambio de jeringuillas en el Centro Penitenciario de Pamplona (España). Rev Esp Sanid Penit 8: 34-40.

- Ministry of the interior: Directorate General for Prisons Ministry of health and consumer affairs: Secretariat of the National AIDS Plan. Key issues for implementation of needle exchange programmes in prisons. SPAIN. Available at http://www.mscbs.gob.es/ciudadanos/enfLesiones/enfTransmisibles/sida/prevencion/

progInterJeringuillas/PIJPrisiones/elemClavePIJIng.htm.

- Arroyo-Cobo JM (2010) Public health gains from health in prisons in Spain. Public Health 124: 629-631. [Crossref]

- Mogg D, Levy M (2009) Moving beyond nonengagement on regulated needle-syringe exchange pro- grams in Australian prisons. Harm Reduct J 6: 7. [Crossref]

- Ferrer-Castro V, Crespo-Leiro MR, García-Marcos LS, Pérez-Rivas M, Alonso-Conde A et al. (2012) Evaluation of a Needle Exchange Program at Pereiro de Aguiar prison (Ourense,Spain): A ten year experience. Rev Esp Sanid Penit 14: 3-11 [Crossref]

- Subdirección General de Sanidad Penitenciaria. Secretaria General de Instituciones Penitenciarias. 1999 Unpublished report. Ministerio de Interior. Madrid

- Hernández-Fernández T, Arroyo-Cobo JM (2010) Results of the Spanish experience: a comprehensive approach to HIV and HCV in prisons. Rev Esp Sanid Penit 12: 86-90. [Crossref]