We report a group of 3 symptomatic nulliparous patients aged 31, 40 and 41 years old, respectively, with polypoid adenomyomas and associated extensive involvement of the endometrium, myometrium, or cervix by adenomyotic tissue. All cases were managed with fertility-sparing surgery. Two patients with endometrial polypoid adenomyomas were treated with laparoscopic excision, and one patient with an atypical endocervical adenomyoma, with hysteroscopic transcervical resection of the tumor, plus laparoscopic excision of uterine adenomyosis and vaginal trachelectomy. All patients reported menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea preoperatively. Minimally invasive surgery resulted in considerable symptomatic improvement, and despite its extent, uterine reconstruction was anatomically very satisfactory. None of the patients has attempted a pregnancy as yet. The 31 years-old patient, within a year from surgery, underwent a hysterosalpingogram which showed a good endometrial cavity but a blocked right tube. The patient with the atypical polypoid endocervical adenomyoma remains in an IVF waiting list. In conclusion, minimally invasive fertility-sparing surgery in symptomatic nulliparous patients with uterine polypoid adenomyomas and associated extensive adenomyosis is challenging. Iatrogenic infertility, recurrence, and malignant transformation are real risks, which should be fully discussed with the patient.

Polypoid adenomyomas (PAMs) are rare and usually present as polypoid submucous tumors projecting into the endometrial cavity resembling endometrial polyps. They usually cause irregular vaginal bleeding or menorrhagia, and occasionally exhibit histologic atypia [1,2]. Their management represents an operative challenge, in particular when they belong to a larger adenomyotic complex, especially in young patients who wish to retain their uterus [3].

We present three cases of symptomatic PAMs in three nulliparous patients with different priorities regarding future pregnancy planning, and variable associated uterine pathology, all wishing preservation of their fertility. All cases had diffuse and extensive uterine adenomyosis, with variable involvement of the myometrium. In one case management was further complicated by tumor atypia and extensive cervical stroma ultra-sonographic irregularity. This last case had been previously presented as an image diagnosis by our team [4], and her follow-up treatment (not previously reported) is presented in this paper.

Case 1

A 31 year old nulliparous patient presented with irregular vaginal bleeding and anemia. Pelvic ultrasonography revealed a 4.5cm well vascularized, intramural uterine tumor protruding through the posterior aspect of the uterine cavity (Figures 1a-b). Hysteroscopic examination revealed an irregular friable mass occupying almost 3/4 of the cavity (Figures 2a-b). The patient was managed with laparoscopic excision and uterine reconstruction, after fully informed consent for the possibility of malignant transformation. The operation was completed laparoscopically using vasopressin to control blood loss (Figures 3a-d). Uterine reconstruction despite a relatively large gap of the posterior part of the endometrial cavity was very satisfactory (Figures 4a-d). A pediatric Foley catheter was left in situ for 5 days. Final histology was suggestive of a polypoid adenomyoma without cellular atypia (Figures 5a-b).

Figures 1a-b. Ultrasonographic appearance of the 1st polypoid adenomyoma, occupying a significant part of the uterine cavity.

Figures 2a-b. Hystreroscopic view showing an irregular friable polypoid lesion.c d

Figures 3a-d. Laparoscopic excision of the lesion with wedge resection of associated diffuse adenomyosis.

Figures 4a-d: Laparoscopic view of the mass after opening the endometrial cavity, and after its removal and final uterine reconstruction.

Figures 5a-b: Histological appearance of the polypoid adenomyoma.

The patient’s periods were restored to normal without any inter-menstrual bleeding or dysmenorrhea. Eighteen months later she underwent a hysterosalpingography. In comparison to a preoperative exam a year before, the uterine cavity appeared very satisfactory with a smooth outline (Figures 6a-b). The left tube was patent. The right tube appeared blocked at the level of the isthmus. Hysteroscopic re-evaluation of the uterine cavity has been scheduled in the near future, when pregnancy will become desirable. Four years post-surgery she remains well and asymptomatic.

Figures 6a-b: Hysterosalpingogram showing a grossly distorted cavity before, and a normal cavity with right tubal occlusion after the procedure.

Case 2

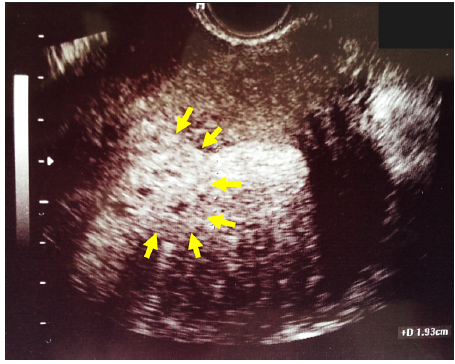

A 40 years old nulliparous patient presented with meno-metrorrhagia and severe dysmenorrhea. A pelvic ultrasound scan revealed the presence of diffuse adenomyosis. At the level of the fundus the endometrial cavity was distorted by a polypoid irregular mass measuring 1.9x1.7x1.5cm (Figure 7). She was scheduled for diagnostic hysteroscopy and laparoscopic management of her adenomyosis.

Figure 7: Ultrasonographic appearance of the 2nd polypoid adenomyoma distorting the fundal area of the cavity (arrows), with associated adenomyotic myometrium.

At the day of her surgery she reported heavy vaginal bleeding and while the hysteroscopy was postponed, she opted to go ahead with laparoscopy. During surgery which was completed laparoscopically using vasopressin to control blood loss, it was discovered that adenomyosis affected an extensive area of her fundal, anterior and posterior myometrium with poorly defined margins (Figures 8a-b). An attempt was made to preserve as much uterine wall as possible for reconstruction of her uterus, and at the same time to remove the large bulk of the tumor. During dissection we intentionally entered the uterine cavity and found that the polypoid mass was continuous with the adenomyotic tissue and was removed en block with it. Uterine reconstruction was very satisfactory.

Figures 8a-b: Extensive adenomyosis of the myometrium (8a), and resected mass. The limits of the adenomyoma and normal endometrium are outlined (8b).

Final histology revealed a polypoid adenomyoma and extensive infiltration of the myometrium by dense adenomyotic tissue.

The patient made an uneventful recovery. Her periods returned to normal, with considerable improvement of her dysmenorrhea. At 36 months follow-up she remains very satisfied with her symptoms, but has not attempted a pregnancy yet. She declined to undergo an evaluation of her uterine cavity with either hysteroscopy or hysterosalpingography.

Case 3

A 41 years-old nulliparous woman presented with meno-metrorrhagia. On ultra-sonographic examination she had been diagnosed with a type 2, 5cm submucous fibroid and uterine adenomyosis. The patient had recently entered an IVF program. She was scheduled for hysteroscopic evaluation.

At hysteroscopy, her endometrial cavity was grossly distorted by the fibroid. At the level of the isthmus, a 2cm polypoid tumor with an irregular micro-papillary surface was discovered. Three small endometrial polyps were also found. The tumor was completely resected down to its’ base with a 27Fr bipolar loop resectoscope. It was decided at that stage, not to perform any further surgery, and to review the patient’s case with histological diagnosis. Final histology was suggestive of an atypical polypoid adenomyoma.

The patient was treated conservatively, after signing a fully informed consent, with hysteroscopic removal of her polyps, laparoscopic enucleation of the fibroid, and wedge resection of the adenomyotic uterine wall. All specimens were negative for malignancy.

A follow-up transvaginal scan was performed 3 months later. The cervical stroma was found harbouring a large hypoechoic poly-microcystic area with increased vascularity (Figures 9a-b). In view of her recent history and histological diagnosis, it was considered suspicious for malignant transformation. The options of hysterectomy and trachelectomy were discussed with her, and she opted again for the fertility-sparing procedure. The operation was performed vaginally. After simple trachelectomy a permanent cerclage No 1 Prolene suture was placed. Histology of the cervical specimen was suggestive of stromal adenomyosis without atypical changes. The patient remains in the IVF waiting list.

Figures 9a-b: Ultrasonographic extensive irregularity of the cervix, in the patient with the atypical endocervical polypoid adenomyoma.

To the best of our knowledge this is the first report of polypoid adenomyomas with extensive associated uterine involvement by adenomyosis, exclusively in symptomatic nulliparous patients wishing to retain their full reproductive capacity. This group of patients’ represents 37.5% of a total of 8 cases with PAMs treated in our department with conservative surgery over the last 10 years. Such cases represent a real operative challenge for the following reasons:

- Polypoid adenomyomas themselves frequently occupy a large area of the endometrial cavity not sparing the tubal ostia as it was the case in two of our patients.

- Hysteroscopic-only management, obviously less traumatic and frequently adequate for smaller tumors, may not be a real choice in patients with associated extensive myometrial or endocervical involvement by adenomyosis, especially in the presence of severe menorrhagia or dysmenorrhea requiring attention per se.

- Uterine reconstruction represents a real technical challenge after resection of extensive uterine adenomyosis, where radicality should be balanced against a good functional outcome especially in nulliparous patients in whom the uterus should remain adequate to conceive and accommodate a term pregnancy.

- Laparoscopic management of such patients requires high levels of technical skills, both for the purpose of excising adequately adenomyosis and suturing the uterus, but also for removing radically the polypoid adenomyoma without compromising the uterine cavity, and destroying – wherever feasible – the integrity of the tubal lumen.

- In the case of endocervical tumors associated with cervical stroma involvement by diffuse adenomyosis, the problem of radical excision is even more complex, as the consequences of such a procedure for the nulliparous patient may be catastrophic causing cervical stenosis, obstruction, or insufficiency, compromising irreparably her future fertility.

Adding to all the above reasons, histologic atypia of the polypoid adenomyoma may further complicate clinical management of the patient with associated extensive adenomyosis, as was the case in our 3rd patient who was offered hysterectomy but opted for trachelectomy. In such cases the possibility of coexistence of the adenomyoma with an adenocarcinoma should always be kept in mind, and the patient should be fully informed on this. Furthermore, in the case of conservative surgery follow-up and surveillance of these patients with atypical tumors and diffuse adenomyosis represents a real headache, as recurrence rates are high and malignant transformation may also occur [5,6]. In a case series of atypical lesions reported by Matsumoto T, et al, there were recurrences in 5 (23.8%) of the 21 patients in who were treated with fertility-sparing surgery. The rates of recurrence were 10% (1/10) in patients treated with hysteroscopic transcervical resection of the PAM and 36.4% (4/11) in those who were managed with other conservative treatment options i.e. dilatation & curettage, or vaginal excision [7].

Histologically uterine adenomyomas are circumscribed nodular aggregates of benign endometrial glands surrounded by endometrial stroma with leiomyomatous smooth muscle bordering the endometrial stromal component. They may be located within the myometrium, or they may involve or originate in the endometrium and grow as polypoid tumors [8,9]. Multifocal development is extremely rare.

- On microscopic examination, adenomyomas are usually well demarcated from the surrounding structures. The endometrial glands are mostly tubular and show relatively regular spacing from each other without any back-to-back arrangement. The glands are lined by benign proliferative pseudostratified columnar epithelium. An occasional typical mitotic figure may be noted in these glands in a few cases. The glands are surrounded by endometrial stroma which is compact and spindly. This stroma is, in turn, bordered by leiomyomatous smooth muscle. Thick-walled blood vessels are commonly observed. One to two typical mitotic figures per 10 hpf may be noted occasionally in the endometrial stroma in a few cases; however, no mitosis should be noted in the myometrial component [8,9]. Associated diffuse adenomyosis has been reported in up to 31% of cases [11]. This had been the case in all 3 of our patients. Adenomyomas have to be distinguished from a number of other benign lesions, for example, adenomyosis, leiomyoma with entrapped glands, endometrial polyps, and adenofibroma. Differential diagnosis of the benign polypoid variant should include the atypical polypoid adenomyoma and adenosarcoma. The former, by definition, has epithelial atypia and the latter a malignant (usually low grade) stromal component with typically absent or inconspicuous smooth muscle. The differential diagnosis of APAM includes complex endometrial hyperplasia with atypia, invasive adenocarcinoma, adenosarcoma and carcinosarcoma. Published series indicate an average risk of endometrial carcinoma of 8.8% in women with a history of polypoid adenomyoma. Distinction of adenomyoma from adenosarcoma may have significant therapeutic implications, particularly in young nulliparous women [12-14].

More frequently PAMs manifest during the reproductive and premenopausal age with a reported mean age of 38-40 years [2,8,9]. They can be found anywhere in the uterine and endocervical cavity, and may vary considerably in size. In a case series of 46 total uterine tumors, 31 were in the corpus, 12 were in the fundus, and 3 were in the isthmus. The mean tumor size was 3.5 cm (range, 0.5-9cm). The tumors were polypoid in 30 cases, pedunculated in 11 cases, and sessile in the remaining 5 cases. Of the pedunculated tumors, 5 protruded into the endocervical canal and 2 had prolapsed into the vagina [15].

According to the same report, 3 distinct ultrasonographic patterns can be recognized: the solid pattern (n=20, %), the solid pattern with cystic areas (n=54, %), and the predominantly cystic pattern (n=4, %). Sonographic features include a heterogeneously isoechoic, polypoid, or pedunculated endometrial mass, with an ill-defined margin, hemorrhagic foci, posterior shadowing, and associated adenomyosis in the myometrium. Knowledge of these sonographic appearances may facilitate the diagnosis of polypoid adenomyoma and help differentiate it from other polypoid uterine tumors [15]. All 3 of our cases demonstrated the most common mixed pattern, with associated posterior shadowing, indicating the presence of extensive coexistent adenomyosis. Only the endocervical tumor showed a predominantly cystic pattern.

In conclusion, conservative operative management of polypoid adenomyomas with co-existing extensive adenomyotic involvement of the endometrial cavity, the myometrium, or the cervical stroma, is challenging in nulliparous patients. Radicality of excision to achieve symptomatic relief should be balanced against iatrogenic consequences on fertility and the risk of recurrence. Atypia of the lesion and the risk of malignancy represent additional considerations for which a fully informed consent should be obtained, for any type of fertility-sparing procedure.

- Longacre TA, Chung MH, Rouse RV, Hendrickson MR (1996) Atypical polypoid adenomyofibromas (atypical polypoid adenomyomas) of the uterus. A clinicopathologic study of 55 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 20: 1-20. [Crossref]

- Heatley MK (2006) Atypical polypoid adenomyoma: a systematic review of the English literature. Histopathology 48: 609-610. [Crossref]

- Dinas K, Daniilidis A, Drizis E, Zaraboukas T, Tzafettas J (2009) Incidental diagnosis of atypical polypoid adenomyoma in a young infertile woman. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 30: 701-703. [Crossref]

- Protopapas A, Sotiropoulou M, Athanasiou S, Loutradis D (2016) Endocervical Atypical Polypoid Adenomyoma. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 23: 130-132. [Crossref]

- Inoue K, Tsubamoto H, Hori M, Ogasawara T, Takemura T (2014) A case of endometrioid adenocarcinoma developing 8 years after conservative management for atypical polypoid adenomyoma. Gynecol Oncol Case Rep 8: 21-23. [Crossref]

- Sugiyama T, Ohta S, Nishida T, Okura N, Tanabe K, et al. (1998) Two cases of endometrial adenocarcinoma arising from atypical polypoid adenomyoma. Gynecol Oncol 71: 141-144. [Crossref]

- Matsumoto T, Hiura M, Baba T, Ishiko O, Shiozawa T, et al. (2013) Clinical management of atypical polypoid adenomyoma of the uterus. A clinicopathological review of 29 cases. Gynecol Oncol 129: 54-57. [Crossref]

- Tahlan A, Nanda A, Mohan H (2006) Uterine adenomyoma: a clinicopathologic review of 26 cases and a review of the literature. Int J Gynecol Pathol 25: 361-365. [Crossref]

- Young RH, Treger T, Scully RE (1986) Atypical polypoid adenomyoma of the uterus. A report of 27 cases. Am J Clin Pathol 86: 139-145. [Crossref]

- Horikawa M, Shinmoto H, Soga S, Shiomi E, Sei K, et al. (2012) Multiple atypical polypoid adenomyoma of the uterus. Jpn J Radiol 30: 606-611.

- Horita A, Kurata A, Komatsu K, Yajima M, Sakamoto A (2010) Coexistent atypical polypoid adenomyoma and complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia in the uterus. Diagn Cytopathol 38: 527-532. [Crossref]

- Zhang HK, Chen WD (2012) Atypical polypoid adenomyomas progressed to endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinomas. Arch Gynecol Obstet 286: 707-710. [Crossref]

- Yamagami W, Susumu N, Ninomiya T, Nakadaira N, Iwasa N, et al. (2015) Hysteroscopic transcervical resection is useful to diagnose myometrial invasion in atypical polypoid adenomyoma coexisting with atypical endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial cancer with suspicious myometrial invasion. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 41: 768-775. [Crossref]

- Matsumoto T, Hiura M, Baba T, Ishiko O, Shiozawa T, et al. (2013) Clinical management of atypical polypoid adenomyoma of the uterus. A clinicopathological review of 29 cases. Gynecol Oncol 129: 54-57. [Crossref]

- Lee EJ, Han JH, Ryu HS (2004) Polypoid adenomyomas: sonohysterographic and color Doppler findings with histopathologic correlation. J Ultrasound Med 23: 1421-1429. [Crossref]