Introduction: Previous studies have shown that syllable speech technique (SST) has the potential to be a useful and practical way to achieve stutter-free speech for children with stuttering (CWS). In this preliminary study, the use of SST in Persian-speaking school-age CWS was investigated.

Materials and methods: Ten 8-to-11-year-old students with stuttering were entered the study as participants. We tried to enhance their speech fluency using SST accompanied by verbal encouragement for stutter-free speech. The outcome measures (primary and secondary measures) were evaluated in three-time sections, including before (T0), after (T1), and one month after intervention (T2). Participants' scores and the mean ± SD of outcomes are presented in tables.

Results: The children showed significantly better scores on all primary and secondary measures at T1 (p ≤ 0.004) and T2 (p ≤ 0.005) compared with T0. There was no significant difference between T1 and T2 (p ≥ 0.026).

Conclusion: The reported benefits of SST in stuttering reduction and speech-related anxiety relieving of Persian-speaking school-age CWS confirms the feasibility and usefulness of this technique.

stuttering, syllabic speech technique, school-age speakers

Stuttering, as a motor speech disorder, is known as repeats, blocks, or prolongations on speech units such as phonemes, syllables, and words [1]. The prevalence of stuttering is near to 1% among population [2]. Although about 70% of children naturally recover from primary stuttering before the age of 7 [3], most school-age children with stuttering (CWS) need speech therapy programs to improve or reduce the severity of stuttering. As CWS enter primary school and become more aware of their speech characteristics, they become frustrated because they experience negative stuttering reactions from classmates. More than 80% of school-age CWS are reported to be ridiculed by classmates for stuttering [4]. These children often have a negative attitude towards their own verbal communication. Frustration, shame, and hatred are some of the most common feelings of stuttering; however, as the child grows into adolescence, these feelings gradually get worse [4]. Researchers have emphasized that if these unpleasant verbal experiences continue, stuttering will become more complex at later ages and can even affect friend-finding and job search [5,6].

In general, stuttering treatment for school-age CWS can be divided into direct and indirect strategies. Indirect strategies improve the child's communicative verbal environment by slowing down parents' speaking speed, speech turn-taking and eliminating stressors [1]. In these strategies, the CWS would have been required to change the rate, rhythm, style, or prosody of speech [1]. The importance of direct stuttering treatments for CWS at school age is due to the worsening of stuttering symptoms (e.g., repeats, blocks, or prolongations) and negative experiences at this age. If primary speech dysfluencies in CWS are neglected, there is a risk of adding secondary behaviors (i.e., cognitive, affective, and social problems) to motor stuttering disorders [7]. Therefore, it is necessary to remove the primary speech dysfluencies using fluency-enhancing techniques before the dysfluencies become more complex.

The variability model (V-model) proposes that stuttering occurs when speakers cannot smoothly execute the stressed-syllables of words or sentences as they produce a syllable to next one with additive oro-motor forces [8]. Rhythmic or syllabic speech technique (SST) is known as fluency-enhancing way to eliminate speech dysfluencies in persons with stuttering [9]. In this technique, the words and phrases of sentences have been regularly said in time to rhythmic beats (e.g., This-is-a-car, I-went-to-Teh-ran-ci-ty-with-that). Increasingly, additive stress factor within words and phrases may increase the linguistic demands and CWS will get speech production difficulties [10]. The SST can almost clear stress contrasts across syllables of words and sentences and it can convert the speech to a monotonic style of spoken syllables and reform that to stutter-free speech [9]. According to Trajkovski et al., the simple feasibility of this technique can lead even young CWS to learn and implement its methods [11]. Regardless the more primary studies, Coppola and Yairi, in a 3-single-subject study design, accomplished a programmed instruction of the SST to decrease the stuttering severity. Although they found that stuttering severity had been clinically decreased in two children after 6 weeks of treatment, the within-clinic fluent speech did not generalize to daily activities of verbal communication [12]. Andrews et al., investigated the SST with ten preliminary school-age children who had stuttering. They trained the children and their parents to use a non-programmed treatment format of the SST at comfortable level of speech rates. Findings demonstrated that nine of the participants showed a significant reduction of stuttering [13]. Researchers have strictly suggested that further studies are needed to investigate the relieving effects of the SST on speech dysfluencies in other languages [14,15].

The Persian language, a member of the Indo-European family of languages, is spoken by over 100 million people in Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan and other countries [16]. Like English language, stress can appear on various positions of words in Persian language. For example, the compound nouns /bâz-kon/ which means /opener/ or /pâk-kon/ which means /eraser/, are stressed on the final syllable, while the verb phrases represented by /bâzkon/, which means /open/ and /pâkkon/ which means /clean/, are stressed on the initial syllable [17]. In detail, research regarding efficacy of the SST to treat stuttering in non-English speaking school-age CWS is scarce. Although the relieving effects of this technique on speech dysfluencies in English-speaking CWS is extremely revealed, to the best our knowledge in Persian-language, there is no experimental evidence about the effectiveness of the SST on school-age CWS. The aim for designing this preliminary study, therefore, was to determine the effects of the SST on improving the severity and secondary behaviors of stuttering in Persian-speaking school-age CWS.

Participants

Participants were ten school-age children (6 boys and 4 girls with a mean ± SD age of 9.18 ± 0.89 years) who suffered developmental stuttering. All children were diagnosed as persons who stutter by the first author who is a speech and language pathologist (SLP) and is experienced in stuttering therapy, during screening assessments based on the following formula with a 200-syllables speech sample. According this formula, if the computed dysfluency score was more than 4, the child’s speech was known as stuttering [18,19].

Dysfluency score = [(Part-word repetitions + mono-syllable word repetition) × average repetition units + 2 × the frequency of blocks and prolongations]

The children, who were eligible for the study, were stuttered for more than 12 months prior to the current study. All children had not continued speech therapy sessions for at least 6 months before they participated in the study. All participants had a normal range of IQ. The children and their families were mono-lingual and spoke Persian as their preferred language. Table 1 lists the demographic characteristics of the participants in terms of chronological age, gender, characteristics of their stuttering, and histories. Neither of the participants had co-morbidity, with exception of M.R. who diagnosed as literacy problems and lisp distortion on consonants /s/ and /z/. Eight of the participants previously had short-term speech therapy courses for stuttering disorder, but none of them had training to speak with the SST manner.

Table 1. Description of participants' demographic characteristics.

Participant |

Age (yrs. months) |

Gender |

Co-morbidity |

Age at stuttering onset |

Family history |

Speech therapy history |

A.K. |

10.10 |

F |

N |

3.5 |

N |

Y |

B.Z. |

9.11 |

M |

N |

3.5 |

Y |

Y |

P.Z. |

9.10 |

M |

N |

3 |

Y |

Y |

H.R. |

9.11 |

M |

N |

3 |

N |

Y |

E.N. |

10.10 |

F |

N |

4 |

Y |

Y |

B.T. |

8.02 |

M |

N |

3 |

N |

N |

H.K. |

8.09 |

F |

N |

5 |

N |

Y |

K.R. |

8.03 |

F |

N |

3 |

N |

N |

M.S. |

10.11 |

M |

N |

4 |

N |

Y |

M.R. |

10.05 |

M |

Y |

4.5 |

Y |

Y |

Mean or Ratio |

9.18 ± 0.89 |

F/M: 4/6 |

Y/N: 1/9 |

3.7 ± 0.71 |

Y/N: 4/6 |

Y/N: 8/2 |

M: male, F: female, %SS: percentage of stuttering severity, yrs: years, mons: months, Y: yes, N: no

Study design

The children were studied with a single-group pretest-posttest design across participants. The SST treatment was implemented in three stages (Table 2). During stage 1, the participants and their parents attended the clinic twice a week (one-hourly sessions) to learn the principles and patterns of the SST and familiarize with the tasks. Imitation and rehearsal were utilized to reach patterns of the SST at near natural-sounding speech rate and intonation in stage 2. The parents were asked to reinforce the SST usage at home, and they insisted that the children utilize it in daily verbal communication (e.g., book-reading, storytelling, shopping, and driving in the car). Although the efficacy of stuttering treatment on school-age CWS is dependent on interaction between several factors such as, cognitive, linguistic, or motor factors [7,20], it has been suggested that the verbal reinforcement showed some beneficial effects on CWS treatment [21]. Verbal reinforcement was, therefore, presented when the parent and child verbally interacted together and when the child wanted to verbally communicate with others. These reinforcements involved positive sentences, for example, “That was excellent talking!” or “Well done! I think you spoke very smooth”. The clinician also trained the parents to use declarative feedback for stuttered moments of speech with asking sentences consist of “That was a bit stressful word, can you syllabically say that again, robotic manner?”. In stage 3, the clinician tried to generalize and transfer the learned methods into the communication-related activities daily living of the children such as parent-, friends-, or other interlocutors-child verbal interactions. Totally, twelve therapeutic sessions had been held at 1.5 months for the participants.

Table 2. Protocol of treatment.

Step |

Procedure |

S1 |

Goal:

The children and their parents accept rationale of the SST and learn to utilize it.

Instructions:

To display and model the concept of cadence and beats.

To use finger, tap on table and utter one syllable per second.

To liken the SST manner to "Robot speech".

The children encouraged by parents within therapeutic sessions. |

S2 |

Goal:

The children generalized the SST to various speech tasks.

Instructions:

To increase the number of beats per minute to 120 beats per minute (bpm).

To perform the SST in reading, answering, and monologue with model as needed. |

S3 |

Goal:

Increasing the self-regularity and transferring the technique to activities daily living.

Instructions:

To design and perform home assignments with optimal bpm rate.

To conduct brief beyond-clinic exercises along with supervision by therapist.

To analyze the contingent stuttering during speech by self.

If stuttering occurs parents supported children, but gradually withdraw the SST practice with the children. |

Outcomes of the study were divided into primary and secondary measures. The percentage of stuttered syllables (%SS), and stuttering severity based on 3rd Persian version of stuttering severity instrument (SSI-3) at clinic environment were considered as primary outcome measures; and stuttering severity rating (SR) based on parents' assessment at home, self-reported speech satisfaction based on Persian version of communication attitude test (CAT), and speech quality rating based on teacher-report questionnaire were scaled as secondary outcome measures.

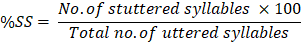

Measure %SS, an index which is agreed between clinicians as stuttering severity scale [22], was compared at three sections of the study: before intervention (T0), immediately after intervention (T1), and one month after the end of intervention (T2). For calculation of %SS at each section of treatment, we recorded a 3-minutely spontaneous speech sample of the children from two different situations (within- and beyond-clinically conversation). The .mp3 format of speech samples were audio-recorded using a Sunny JXD/D61 digital sound-recorder (made in China). The children's speech samples were given to a blinded SLP who is experienced in stuttering assessment. She counted the total number of uttered-syllables, the number of stuttered syllables, and then calculated the %SS using the following formula:

In order to calculate the clinical stuttering severity, the SSI-3 was used for each child at three sections of the study. This test is a reliable and valid instrument for Persian-speaking children [23]. Based on the SSI-3 in CWS, the scores under 10 represent very mild stuttering; the scores between 11 and 16 show mild stuttering; the scores between 17 and 26 indicate moderate stuttering; the scores between 27 and 31 indicate severe stuttering, and scores above 32 show advanced stuttering. The SSI-3 has a good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha > 0.80) and sufficient test-retest reliability (r > 0.80) [23]. Total overall score of SSI-3 consists of stuttering frequency score, score of the average length of three longest stuttering moments, and score of physical concomitants with stuttering was computed via two tasks of spontaneous speech and book-reading at three time-sections of treatment.

The trained parents were obligated to daily document the SR of the child's stuttering using a 8-point severity rating scale where 1 = no stuttering, 2 = very mild, 3 = mild, 4 = mild to moderate, 5 = moderate, 6 = moderate to severe, 7 = severe, and 8 = extremely severe stuttering. The parents should be quantitatively rated the severity of stuttering-like behaviors. Ultimately, the average score of SR belongs to first week of treatment, first week immediately post-treatment, and the last week of one month after treatment were respectively considered as pre-treatment, post-treatment, and follow-up scores for the children's SR.

The Persian-version of CAT for school-age children is a suitable instrument (with CVR = 0.95, and ICC = 0.91) that can assess speech related attitude of students who stutter [24]. This test is including 35 declarative sentences so that each sentence has negative or positive value to assess the verbal communication attitude of CWS. If student say /Yes/ to a sentence with negative value, s/he take zero point for that sentence and reversely if say /No/ to that sentence, s/he take 1 point. Also, answering /Yes/ to a sentence with positive value would have gained 1 point and answering /No/ to that would have scored zero point. In order to CAT, a student may be received from 0 to 35 scores regarding her/the verbal communication attitude. Based on the Persian version of CAT in school-age children, the scores under 11 represent completely negative attitude, the scores from 11 to 19 show negative attitudes, the scores from 20 to 24 indicate moderate attitude, the scores from 25 to 31 indicate positive attitude, and scores above than 31 show completely positive attitude [25]. This test was used to self-rate the attitude of the participants concerning their verbal communication beliefs and feelings at three sections of the study.

A teacher-report questionnaire (Appendix A), self-structured by the authors, was given children's teachers at three sections of treatment (before, immediately, and one month after the end of treatment) to evaluate the social validity of the interventions. Briefly, social validity of a practical intervention is known as the number of benefits of a clinical technique to resolve the disorder-induced other problems in everyday life [26]. For example, we assumed that if teachers report that children's oral school-tasks after stuttering treatments became better than before it, we will then conclude the treatment effects were meaningful and socially is valid. The sum of the scores of the statements was considered as total score of the teacher-report questionnaire. The range (minimum to maximum) of total score of each child on this questionnaire was changeable from 4 to 20.

Reliability

At the end of treatment, the children's speech samples were given to an assessor, who was unfamiliar with the purpose of the study, the conditions under which the speech samples were elicited, and the identity of the participants, for counting the number of total uttered/stuttered syllables, determining the stuttering frequency, and computing the average length of three longest stuttering moments. To more precisely calculate the children's %SS and total overall score of SSI-3, the assessor was asked twice at a week interval to score them and her total of the outcome assessment recordings were selected to confirm intra-rater agreement as the consistency with which one rater assigns scores (27). The percentage of intra-rater agreement was computed using the following formula and a score of greater than 90% was taken as acceptable.

The percentage of intra-rater agreement of the %SS and total overall score of SSI-3 were greater than 97%. All disagreements between the assessor and the authors were removed by discussion with the first author.

Statistical analysis

In this study, continuous variables are presented as Mean ± SD and discontinuous variables are presented as frequency (or percentage of frequency). Whereas the distribution of the data using the one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was not normal, the nonparametric Friedman's test with post hoc Wilcoxon signed ranks test (WSRT) was used to determine the within-subjects (the sections of treatment) differences for all independent variables. The level of significance was set at p ≤ 0.01 for the data.

As noted earlier, the outcome measures of the current study were divided to two primary and secondary groups. This section reports the findings related to each outcome measure group. The percentage of stuttered syllables, and stuttering severity based on 3rd Persian version of stuttering severity instrument were calculated as primary treatment outcomes. Here, we reported the findings of these outcomes, separately.

For each child, %SS scores were calculated at three time-sections of testing (T0, T1, and T2) that are exhibited in Table 3. The group mean ± SD of %SS at pre-treatment, immediately post-treatment, and one month after the end of treatment were 11.5 ± 7.1, 2.0 ± 1.6, and 2.5 ± 2.1, respectively. The within-group comparisons showed that the participants had significantly lower %SS at T1 and T2 than T0 (p = 0.005), but the mean of %SS at T2 was not significantly different with T1 (p = 0.035).

Table 3. The percentage of stuttered syllables in three time-sections of testing.

Participant |

Sections of computing the %SS |

Testa,b, p value* |

T0 |

T1 |

T2 |

A.K. |

4.7 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

χ2 = 17.7, p < 0.001

[WSRT: Z = -2.8, p = 0.005 for T1 and T2 vs. T0, but WSRT: Z = -2.1, p = 0.035 for T2 vs. T1] |

B.Z. |

14.0 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

P.Z. |

7.4 |

1.4 |

1.5 |

H.R. |

16.5 |

3.1 |

3.6 |

E.N. |

12.4 |

1.9 |

2.8 |

B.T. |

4.9 |

0.6 |

1.0 |

H.K. |

6.0 |

0.2 |

0.5 |

K.R. |

5.7 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

M.S. |

18.2 |

4.2 |

4.0 |

M.R. |

25.5 |

4.9 |

7.3 |

Mean ± SD |

11.5 ± 7.1 |

2.0 ± 1.6 |

2.5 ± 2.1 |

SD: standard deviation; T0: before treatment; T1: immediately after treatment; T2: one month after the end of treatment; Testa,b: Friedman's test with post hoc Wilcoxon signed ranks test (WSRT). p*: within group comparison. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.01.

For each participant, within-clinic total score of stuttering severity was evaluated by the blinded assessor. The group mean ± SD of stuttering severity at pre-treatment, immediately post-treatment, and one month after the end of treatment were 17.6 ± 4.1, 10.5 ± 3.0, and 11.7 ± 3.8, respectively. The within-group comparisons showed that the participants had significantly lower stuttering severity score at T1 and T2 than T0 (p = 0.004), but the mean of stuttering severity score at T2 was not significantly different with T1 (p = 0.026) (Table 4).

Table 4. The participants' SSI-3 scores in three time-sections of testing.

Participant |

Sections of testing the SSI-3 |

Testa,b, p value*

χ2 = 18.7, p < 0.001

[WSRT: Z = -2.8, p = 0.004 for T1 and T2 vs. T0, but WSRT: Z = -2.2, p = 0.026 for T2 vs. T1] |

T0 |

T1 |

T2 |

A.K. |

15 |

9 |

9 |

B.Z. |

17 |

10 |

10 |

P.Z. |

18 |

9 |

11 |

H.R. |

17 |

11 |

12 |

E.N. |

18 |

11 |

13 |

B.T. |

15 |

9 |

10 |

H.K. |

14 |

8 |

8 |

K.R. |

14 |

8 |

8 |

M.S. |

19 |

12 |

16 |

M.R. |

28 |

18 |

20 |

Mean ± SD |

17.6 ± 4.1 |

10.5 ± 3.0 |

11.7 ± 3.8 |

SD: standard deviation; SSI-3: stuttering severity instrument-3rd edition; T0: before treatment; T1: immediately after treatment; T2: one month after the end of treatment; Testa,b: Friedman's test with post hoc Wilcoxon signed ranks test (WSRT). p*: within group comparison. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.01.

The stuttering severity rating (SR) according the parent opinion, self-reported speech satisfaction based on the Persian version of communication attitude test (CAT), and speech quality based on teacher-report questionnaire were scaled as secondary outcome measures and reported the findings of these outcomes.

The stuttering SRs were gathered based on parent opinion and showed in Table 5. The group mean ± SD of the stuttering SR at pre-treatment, immediately post-treatment, and one month after the end of treatment were 5.7 ± 0.9, 3.9 ± 0.8, and 3.9 ± 0.8, respectively. The within-group comparisons showed that the participants had significantly lower SR at T1 and T2 than T0 (p = 0.005), but the mean of SR at T2 was not significantly different with T1 (p = 0.035).

Table 5. The participants' stuttering severity rating in three time-sections of testing.

Participant |

Sections of testing the SR |

Testa,b, p value* |

T0 |

T1 |

T2 |

A.K. |

5.4 |

3.5 |

3.6 |

χ2 = 16.8, p < 0.001

[WSRT: Z = -2.8, p = 0.005 for T1 and T2 vs. T0, but WSRT: Z = -2.4, p = 0.035 for T2 vs. T1] |

B.Z. |

5.6 |

3.3 |

3.4 |

P.Z. |

5.6 |

2.6 |

2.5 |

H.R. |

5.9 |

3.6 |

3.6 |

E.N. |

4.9 |

3.9 |

4.0 |

B.T. |

4.6 |

3.3 |

3.4 |

H.K. |

5.2 |

4.1 |

4.1 |

K.R. |

5.5 |

4.1 |

4.2 |

M.S. |

6.1 |

4.8 |

4.9 |

M.R. |

7.8 |

5.3 |

5.5 |

Mean ± SD |

5.7 ± 0.9 |

3.9 ± 0.8 |

3.9 ± 0.8 |

SR: severity rating; SD: standard deviation; T0: before treatment; T1: immediately after treatment; T2: one month after the end of treatment; Testa,b: Friedman's test with post hoc Wilcoxon signed ranks test (WSRT). p*: within group comparison. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.01.

All children were asked to self-report their beliefs and attitude regarding the verbal communication using the Persian version of the CAT. The group mean ± SD of CAT scores at pre-treatment, immediately post-treatment, and one month after the end of treatment were 19.6 ± 5.4, 23.7 ± 3.7, and 23.5 ± 3.4, respectively. The within-group comparisons showed that the participants had significantly higher CAT score at T1 and T2 than T0 (p = 0.005), but the mean of CAT score at T2 was not significantly different with T1 (p = 0.414) (Table 6). The minimum and maximum scores of participants' CAT showed that their communication attitude had increasingly inclined to positive degrees from T0 compared to T1 and even T2.

Table 6. The participants' mean ± SD (Min-Max) of CAT scores in three time-sections of testing.

Participant |

Sections of testing the CAT |

Testa,b, p value* |

T0 |

T1 |

T2 |

A.K. |

19 |

20 |

20 |

χ2=16.8, p < 0.001

[WSRT: Z = -2.8, p = 0.005 for T1 and T2 vs. T0, but WSRT: Z = -0.8, p = 0.414 for T2 vs. T1] |

B.Z. |

17 |

22 |

21 |

P.Z. |

25 |

29 |

28 |

H.R. |

24 |

25 |

26 |

E.N. |

23 |

27 |

26 |

B.T. |

23 |

25 |

25 |

H.K. |

24 |

26 |

26 |

K.R. |

20 |

26 |

25 |

M.S. |

11 |

19 |

20 |

M.R. |

10 |

18 |

18 |

Mean ± SD (Min-Max) |

19.6 ± 5.4 (10-25) |

23.7 ± 3.7 (18-29) |

23.5 ± 3.4 (18-28) |

SD: standard deviation; Min: minimum; Max: maximum; CAT: communication attitude test; T0: before treatment; T1: immediately after treatment; T2: one month after the end of treatment; Testa,b: Friedman's test with post hoc Wilcoxon signed ranks test (WSRT). p*: within group comparison. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.01.

Table 7 shows the descriptive data in addition to within-group comparisons for the total score of teacher-report questionnaire. The group mean ± SD of the total score of teacher-report questionnaire at T0, T1, and T2 were 11.1 ± 2.1, 14.7 ± 1.3, and 14.7 ± 1.6, respectively. Analysis also showed that, based on teacher's opinion, all participants performed significantly better on the verbal and behavioral functions in classroom/school after stuttering therapy and even at one month after treatment than T0.

Table 7. The participants' mean ± SD (Min-Max) of total score of teacher-report questionnaire in three time-sections of testing.

Participant |

Sections of using the teacher-report questionnaire |

Testa,b, p value* |

T0 |

T1 |

T2 |

A.K. |

11 |

15 |

16 |

χ2=17.6, p< 0.001

[WSRT: Z = -2.8, p = 0.005 for T1 and T2 vs. T0, but WSRT: Z < -0.1, p > 0.999 for T2 vs. T1] |

B.Z. |

12 |

16 |

16 |

P.Z. |

13 |

15 |

16 |

H.R. |

13 |

15 |

15 |

E.N. |

12 |

15 |

15 |

B.T. |

13 |

16 |

15 |

H.K. |

12 |

16 |

16 |

K.R. |

9 |

14 |

14 |

M.S. |

8 |

13 |

13 |

M.R. |

8 |

12 |

11 |

Mean ± SD (Min-Max) |

11.1 ± 2.1 (8-13) |

14.7 ± 1.3 (12-16) |

14.7 ± 1.6 (11-16) |

SD: standard deviation; Min: minimum; Max: maximum; T0: before treatment; T1: immediately after treatment; T2: one month after the end of treatment; Testa,b: Friedman's test with post hoc Wilcoxon signed ranks test (WSRT). p*: within group comparison. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.01.

The purpose of this preliminary trial study was to assess the effects of the SST on relieving the primary and secondary problems in Persian-speaking students with stuttering. In the present study, the clinician and parents presented the SST accompanied by verbal contingencies for stutter-free speech to the school-age CWS. Andrews et al., previously used similar therapeutic protocol to reduce stuttering severity and secondary avoidance behaviors in one group of English-speaking school-age CWS. Although their findings revealed a 77% stuttering severity reduction based on %SS and nearly 82% amelioration of avoidance situations from pre-treatment to 12 months post-treatment, there were remained some avoidance behaviors in the children at the end of study. They suggested that further studies are needed to investigate the effects of this therapeutic program on the various aspects of children's stuttering [15]. However, our findings were consistent with them so that we observed that alike the English-speaking school-age CWS who could have easily reduced %SS, the Persian-speaking school-age CWS could notably eliminate their dysfluencies of speech by using a 1.5-monthly of the SST schedule. All of children, exception of M.S. and M.R. who had the %SS equal to 4.2% and 4.9% and the mean score of SR equal to 4.8 and 5.3 at T1, received to stutter-free speech at T1 and could maintain this skill at follow up step (T2). Trajkovski et al., had reported their participants, who were three preschool children with stuttering, could accede from 13.0 %SS to 1.0 %SS in controlled speaking situations only after below 9 therapeutic sessions of the SST. In view of the low sample size and lack of data regarding the follow up step in their study, they concluded that future studies are needed to design the trial studies with larger groups of CWS, longer period of the SST program and considering the socio-communicative effects of the technique as the outcome measures [14]. We, however, had conducted a multiple baseline design of preliminary study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of the SST program on improving stuttering-like dysfluencies in three Persian-language children with Down syndrome aged below 15 years. Although this fluency-enhancing technique could alter stuttering-like behaviors from phonemic tonic-spasm to simple word repetition, the score of stuttering severity of them did not significantly decrease at post-treatment [28].

The mean SSI-3 score for the children at three sections of testing was the other index which considered as primary consequence of treatment. The findings showed that the SST program could positively influence on the participant's fluency of speech. Although, we did not observe a significant change in the score of stuttering severity of children with Down syndrome who were stuttered due to use of the SST [28], the present findings are corroborative evidence for the benefits of the SST to alter the prosodic characteristics of speech school-age CWS from plosive and stressful way to monotonic and unstressed stutter-free style of speech. Decreasing in severity of stuttering-like dysfluencies is the first target of stuttering therapy in children [9]. Gains in the mean scores of SSI-3 as well as %SS were observed in the participants supporting the feasibility of the SST in school-age CWS and indicated that this technique can be an effective way to deduce the severity of stuttering behaviors for school-age CWS.

Since stuttering therapy must have a comprehensive approach to all stuttering-induced problems (e.g., cognitive, affective, or social problems), the primary improvements of the participants had been confirmed by parent-report SR, self-report CAT, and teacher-report questionnaires. The findings revealed all participants increasingly reached to a comfortable level of satisfaction of verbal communication as well as stuttering severity reduction at T1 and even T2 compared with T0. The parents, teachers, and their own children reported that control of stuttering behaviors could help to eliminate symptoms of speech-related anxiety after passing the treatment phases. Although a review of the literature showed that there is no creditable information to report the social validity of the SST program, the current result is consistent with other studies [13,15,29]. These researchers reported that the SST as a fluency-shaping technique is an enjoyable, simple, and cost-efficient procedure to immediately make fluent speech as well as self-respect in the school-age CWS. Finally, this trial study without control group show that a simple procedure of the SST accompanied verbal reinforcements can easily lead to notable and stable stutter-free speech in Persian-speaking CWS.

The type of stuttering and its complications (as seen M.R.) may affect treatment outcomes. So, for these children must be considered continued practice of various techniques or it is likely that a comprehensive approach is necessity to reconstruct the style of child's speech.

This article is part of the M.Sc. dissertation in speech therapy of Mohammad Soroush Mehdifard.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

The research was approved and funded by Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Iran (grant reference number: PHT-9744).

- Guitar B (2006) Stuttering: An integrated approach to its nature and treatment (3rd ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

- Bloodstein O (1996) A handbook on stuttering (5th ed.). San Diego, CA: Singular Publishing Group.

- Mansson H (2000) Childhood stuttering: Incidence and development. J Fluency Disord 25: 47-57.

- Bloodstein O (2001) Incipient and developed stuttering as two distinct disorders: Resolving a dilemma. J Fluency Disord 35: 67-73.

- Kraaimaat FW, Vanryckeghem M, Van Dam-Baggen R (2002) Stuttering and social anxiety. J Fluency Disord 27: 319-331. [Crossref]

- Messenger M, Onslow M, Packman A, Menzies R (2004) Social anxiety in stuttering: Measuring negative social expectancies. J Fluency Disord 29: 201-212. [Crossref]

- Bonelli P, Dixon M, Bernstein Ratner N, Onslow M (2000) Child and parent speech and language following the Lidcombe programme of early stuttering intervention. Clin Linguist Phone 14: 427-446.

- Packman A, Onslow M, Richard F, van Doorn J (1996) Syllabic stress and variability: A model of stuttering. Clin Linguist Phone 10: 235-263.

- Ham RE (1988) Unison speech and rate control therapy. J Fluency Disord 13: 115-126.

- Packman A, Code C, Onslow M (2007) On the cause of stuttering: Integrating theory with brain and behavioral research. J Neurolinguist 20: 253-262.

- Trajkovski N, Andrews C, O'Brian S, Onslow M, Packman A (2006) Training stuttering in a preschool child with syllable timed speech: a case report. Behavior Chang 23: 270-277.

- Coppola V, Yairi E (1982) Rhythmic speech training with preschool stuttering children: an experimental study. J Fluency Disord 7: 447-457.

- Andrews C, O’Brian S, Harrison E, Onslow M, Packman A, et al. (2012) Syllable-timed speech treatment for school-age children who stutter: A phase I trial. Lang Speech Hear Serv School 43: 359-369. [Crossref]

- Trajkovski N, Andrews C, Onslow M, Packman A, O'Brian S, et al. (2009) Using syllable-timed speech to treat preschool children who stutter: A multiple baseline experiment. J Fluency Disord 34: 1-10. [Crossref]

- Andrews C, O’Brian S, Onslow M, Packman A, Menzies R, et al. (2016) Phase II trial of a syllable-timed speech treatment for school-age children who stutter. J Fluency Disord 48: 44-55. [Crossref]

- Kazemi Y, Klee T, Stringer H (2015) Diagnostic accuracy of language sample measures with Persian-speaking preschool children. Clin Linguist Phone 1-15. [Crossref]

- Mohammad Ebrahimi Jahromi Z, Haghshenas AM (2004) The structure of VP core in standard Persian. J Letter Lang 12: 153-177.

- Guitar B, McCauley RJ (2010) Treatment of stuttering: Established and emerging approaches. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Yairi E, Ambrose NG (1999) Early childhood stuttering I: Persistency and recovery rates. J Speech Lang Hear Res 42: 1097-1112. [Crossref]

- Craig A, Hancock K, Chang E, McCready C, Shepley A, et al. (1996) A controlled clinical trial for stuttering in persons aged 9 to 14 years. J Speech Hear Res 39: 808-826. [Crossref]

- Koushik S, Shenker R, Onslow M (2009) Follow-up of 6-10 year-old stuttering children after Lidcombe program treatment: a phase I trial. J Fluency Disord 34: 279-290. [Crossref]

- Rezai H, Tahmasebi N, Zamani P, Haghighizadeh MH, Afshani M, et al. (2017) Duration of Stuttered Syllables Measured by “Computerized Scoring of the Stuttering Severity (CSSS)” and “Pratt”. Iranian Rehabil J 15: 79-86.

- Bakhtiar M, Seifpanahi S, Ansari H, Ghanadzade M, Packman A (2010) Investigation of the reliability of the SSI-3 for preschool Persian-speaking children who stutter. J Fluency Disord 35: 87-91. [Crossref]

- HosseinZadeh N, Shahbodaghi MR, Jalaei S (2010) Reliability and validity of Behavioral Checklist and Communication Attitude Test in stuttering children and comparison with non-stutters at 6-11 years old. J Modren Rehabil 4: 30-37.

- Yadegari F, Daruei A, Farazi M (2004) Communication Attitude Test (1sted.). Tehran: University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Publications.

- Kazdin AE (1980) Acceptability of alternative treatments for deviant child behavior. J Applied Beh Analys 13: 259-273. [Crossref]

- Bartko J (1976) On various intra-class correlation reliability coefficient. Psychol Bulltin 83: 762-765.

- Zamani P, Mousavi SM, Rezai H (2014) A three-case study on the effectiveness of syllabic-timed method on treating stuttering in children with Down Syndrome. Jundishapur Sci Med J 13: 513-520.

- Trajkovski N, Andrews C, Onslow M, O'Brian S, Packman A, et al. (2011) A phase II trial of the Westmead Program: Syllable-timed speech treatment for pre-school children who stutter. Int J Speech Lang Pathol 13: 500-509. [Crossref]

Editorial Information

Editor-in-Chief

Michael A. Portman

University of Washington, USA

Article type

Research Article

Publication History

Received: July 23, 2020

Accepted: August 10, 2020

Published: August 14, 2020

Copyright

©2020 Zamani P. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation

Zamani P, Tahmasebi N, Mehdifard MS, Hesam S (2020) Syllabic speech technique to decline stuttering severity and its concomitants in Persian-speaking school-age children with stuttering: A preliminary study from Iran. Pediatr Dimensions 5: DOI: 10.15761/PD.1000209.

Table 1. Description of participants' demographic characteristics.

Participant |

Age (yrs. months) |

Gender |

Co-morbidity |

Age at stuttering onset |

Family history |

Speech therapy history |

A.K. |

10.10 |

F |

N |

3.5 |

N |

Y |

B.Z. |

9.11 |

M |

N |

3.5 |

Y |

Y |

P.Z. |

9.10 |

M |

N |

3 |

Y |

Y |

H.R. |

9.11 |

M |

N |

3 |

N |

Y |

E.N. |

10.10 |

F |

N |

4 |

Y |

Y |

B.T. |

8.02 |

M |

N |

3 |

N |

N |

H.K. |

8.09 |

F |

N |

5 |

N |

Y |

K.R. |

8.03 |

F |

N |

3 |

N |

N |

M.S. |

10.11 |

M |

N |

4 |

N |

Y |

M.R. |

10.05 |

M |

Y |

4.5 |

Y |

Y |

Mean or Ratio |

9.18 ± 0.89 |

F/M: 4/6 |

Y/N: 1/9 |

3.7 ± 0.71 |

Y/N: 4/6 |

Y/N: 8/2 |

M: male, F: female, %SS: percentage of stuttering severity, yrs: years, mons: months, Y: yes, N: no

Table 2. Protocol of treatment.

Step |

Procedure |

S1 |

Goal:

The children and their parents accept rationale of the SST and learn to utilize it.

Instructions:

To display and model the concept of cadence and beats.

To use finger, tap on table and utter one syllable per second.

To liken the SST manner to "Robot speech".

The children encouraged by parents within therapeutic sessions. |

S2 |

Goal:

The children generalized the SST to various speech tasks.

Instructions:

To increase the number of beats per minute to 120 beats per minute (bpm).

To perform the SST in reading, answering, and monologue with model as needed. |

S3 |

Goal:

Increasing the self-regularity and transferring the technique to activities daily living.

Instructions:

To design and perform home assignments with optimal bpm rate.

To conduct brief beyond-clinic exercises along with supervision by therapist.

To analyze the contingent stuttering during speech by self.

If stuttering occurs parents supported children, but gradually withdraw the SST practice with the children. |

Table 3. The percentage of stuttered syllables in three time-sections of testing.

Participant |

Sections of computing the %SS |

Testa,b, p value* |

T0 |

T1 |

T2 |

A.K. |

4.7 |

1.0 |

1.1 |

χ2 = 17.7, p < 0.001

[WSRT: Z = -2.8, p = 0.005 for T1 and T2 vs. T0, but WSRT: Z = -2.1, p = 0.035 for T2 vs. T1] |

B.Z. |

14.0 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

P.Z. |

7.4 |

1.4 |

1.5 |

H.R. |

16.5 |

3.1 |

3.6 |

E.N. |

12.4 |

1.9 |

2.8 |

B.T. |

4.9 |

0.6 |

1.0 |

H.K. |

6.0 |

0.2 |

0.5 |

K.R. |

5.7 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

M.S. |

18.2 |

4.2 |

4.0 |

M.R. |

25.5 |

4.9 |

7.3 |

Mean ± SD |

11.5 ± 7.1 |

2.0 ± 1.6 |

2.5 ± 2.1 |

SD: standard deviation; T0: before treatment; T1: immediately after treatment; T2: one month after the end of treatment; Testa,b: Friedman's test with post hoc Wilcoxon signed ranks test (WSRT). p*: within group comparison. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.01.

Table 4. The participants' SSI-3 scores in three time-sections of testing.

Participant |

Sections of testing the SSI-3 |

Testa,b, p value*

χ2 = 18.7, p < 0.001

[WSRT: Z = -2.8, p = 0.004 for T1 and T2 vs. T0, but WSRT: Z = -2.2, p = 0.026 for T2 vs. T1] |

T0 |

T1 |

T2 |

A.K. |

15 |

9 |

9 |

B.Z. |

17 |

10 |

10 |

P.Z. |

18 |

9 |

11 |

H.R. |

17 |

11 |

12 |

E.N. |

18 |

11 |

13 |

B.T. |

15 |

9 |

10 |

H.K. |

14 |

8 |

8 |

K.R. |

14 |

8 |

8 |

M.S. |

19 |

12 |

16 |

M.R. |

28 |

18 |

20 |

Mean ± SD |

17.6 ± 4.1 |

10.5 ± 3.0 |

11.7 ± 3.8 |

SD: standard deviation; SSI-3: stuttering severity instrument-3rd edition; T0: before treatment; T1: immediately after treatment; T2: one month after the end of treatment; Testa,b: Friedman's test with post hoc Wilcoxon signed ranks test (WSRT). p*: within group comparison. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.01.

Table 5. The participants' stuttering severity rating in three time-sections of testing.

Participant |

Sections of testing the SR |

Testa,b, p value* |

T0 |

T1 |

T2 |

A.K. |

5.4 |

3.5 |

3.6 |

χ2 = 16.8, p < 0.001

[WSRT: Z = -2.8, p = 0.005 for T1 and T2 vs. T0, but WSRT: Z = -2.4, p = 0.035 for T2 vs. T1] |

B.Z. |

5.6 |

3.3 |

3.4 |

P.Z. |

5.6 |

2.6 |

2.5 |

H.R. |

5.9 |

3.6 |

3.6 |

E.N. |

4.9 |

3.9 |

4.0 |

B.T. |

4.6 |

3.3 |

3.4 |

H.K. |

5.2 |

4.1 |

4.1 |

K.R. |

5.5 |

4.1 |

4.2 |

M.S. |

6.1 |

4.8 |

4.9 |

M.R. |

7.8 |

5.3 |

5.5 |

Mean ± SD |

5.7 ± 0.9 |

3.9 ± 0.8 |

3.9 ± 0.8 |

SR: severity rating; SD: standard deviation; T0: before treatment; T1: immediately after treatment; T2: one month after the end of treatment; Testa,b: Friedman's test with post hoc Wilcoxon signed ranks test (WSRT). p*: within group comparison. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.01.

Table 6. The participants' mean ± SD (Min-Max) of CAT scores in three time-sections of testing.

Participant |

Sections of testing the CAT |

Testa,b, p value* |

T0 |

T1 |

T2 |

A.K. |

19 |

20 |

20 |

χ2=16.8, p < 0.001

[WSRT: Z = -2.8, p = 0.005 for T1 and T2 vs. T0, but WSRT: Z = -0.8, p = 0.414 for T2 vs. T1] |

B.Z. |

17 |

22 |

21 |

P.Z. |

25 |

29 |

28 |

H.R. |

24 |

25 |

26 |

E.N. |

23 |

27 |

26 |

B.T. |

23 |

25 |

25 |

H.K. |

24 |

26 |

26 |

K.R. |

20 |

26 |

25 |

M.S. |

11 |

19 |

20 |

M.R. |

10 |

18 |

18 |

Mean ± SD (Min-Max) |

19.6 ± 5.4 (10-25) |

23.7 ± 3.7 (18-29) |

23.5 ± 3.4 (18-28) |

SD: standard deviation; Min: minimum; Max: maximum; CAT: communication attitude test; T0: before treatment; T1: immediately after treatment; T2: one month after the end of treatment; Testa,b: Friedman's test with post hoc Wilcoxon signed ranks test (WSRT). p*: within group comparison. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.01.

Table 7. The participants' mean ± SD (Min-Max) of total score of teacher-report questionnaire in three time-sections of testing.

Participant |

Sections of using the teacher-report questionnaire |

Testa,b, p value* |

T0 |

T1 |

T2 |

A.K. |

11 |

15 |

16 |

χ2=17.6, p< 0.001

[WSRT: Z = -2.8, p = 0.005 for T1 and T2 vs. T0, but WSRT: Z < -0.1, p > 0.999 for T2 vs. T1] |

B.Z. |

12 |

16 |

16 |

P.Z. |

13 |

15 |

16 |

H.R. |

13 |

15 |

15 |

E.N. |

12 |

15 |

15 |

B.T. |

13 |

16 |

15 |

H.K. |

12 |

16 |

16 |

K.R. |

9 |

14 |

14 |

M.S. |

8 |

13 |

13 |

M.R. |

8 |

12 |

11 |

Mean ± SD (Min-Max) |

11.1 ± 2.1 (8-13) |

14.7 ± 1.3 (12-16) |

14.7 ± 1.6 (11-16) |

SD: standard deviation; Min: minimum; Max: maximum; T0: before treatment; T1: immediately after treatment; T2: one month after the end of treatment; Testa,b: Friedman's test with post hoc Wilcoxon signed ranks test (WSRT). p*: within group comparison. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.01.