Background: Prophylactic drainage after elective Anterior

resections with stapled colorectal or colo-anal anastomosis decreases neither

the rate of cases with one or more post-operative complications maybe impacted

by drainage nor the complications severity.

Aim and objectives: This study aimed for comparing cases who

experienced routine pelvic drainage with those who didn’t regarding the

complication rate and severity thereafter elective anterior resection (AR).

Subjects and methods: Retrospective cohort study, 54 cases were

arbitrarily allocated into the pelvic drainage group and 29 to the no pelvic

drainage group. All 83 anastomoses were examined for air-tightness

intra-operatively and mended if leak was detected.

Results: This study shows that a statistically significant

change was found among the study groups as (With drainage and Without drainage)

regarding cardiovascular dis, HTN, IHD, drain, open/Lap, covering stoma and mean

mortality during hospital stay.

No significant change statistically was found among the study groups as (With

drainage and Without drainage) as regard post op leak, localized abscess

(infected haematoma), and mortality during hospital stay.

Conclusion: Routine pelvic drainage after elective anterior

resection does not reduce the rate or severity of anastomotic leak. It may,

infrequently, be harmful.

Prophylactic drainage, anterior resection, complications, anastomotic leakage.

The colonic lumen comprises from 108 to 1010 aerobic and

an-aerobic germs /gm of feces. This may clarify why post-operative infectious

complication, the occurrence of it ranged between 10 and 70%, can be more in

cases underwent operations of the colon than in those underwent any other

abdominal operations. Anastomotic leakages are the main reasons of

post-operative infectious complications, accountable for 25- 35% of mortalities

[1].

The Guidelines for Avoidance of Surgical Site Infections (SSIs), made by the

Centers for Diseases Controlling and Preventions (CDC) in 1999, indorses that

‘If drainage is essential, utilize a locked suction drains and eliminate

the drains once it possible’. New RCTs and

metanalyses have maintained the

restricted usage of prophylactic

intraabdominal drainages for several gastro-intestinal operations [2].

Numerous events were defined to reduce the post-operative complications rate and

the severity, particularly infectious side-effects, in addition to the reduction

anastomotic leakages. These comprise anti-biotic prophylaxis, anti-septic

mechanical preparations, diverting stomas, omental wrapping round the

anastomosis, and intra operative air- tightness test resulting in comprehensive

anastomotic air-tightness integrities [3].

The majority of surgeons were supporter repetitive usage of drains after pelvic

anastomose. Proponentes of this maintain that they permit egress of fluids

collection that have the possibility of becoming infected, permit early

recognition of anastomotic dehiscence, and do no harm. Objectors to the use

argue that it can impede healing of the anastomoses confer no benefit and may

cause harm. A recent RCT of pelvic drainage thereafter rectal ressection

suggested that a pelvic drain thereafter rectal resections didn’t present

any advantage to the patients [4].

The prophylactic drainages of the abdomen space were suggested for these same

causes in 1950th. Prophylactic drainage is supposed to (1) reduce the

rate of anastomotic leakages by the evacuation of serositis and blood that, once

contaminated, may cause sore formations and

hole of the abscess

into the inosculation; (2)

reduce the complication severity via early

diagnosing; and (3) ease the diagnosing

of intra- peritoneal hemorrhage [5].

In contrast, surgeons who are opposite to drainage trust that it (1) really

excites the formations of serous fluids; (2) may result in infections from

exterior; (3) rises the rate of leakages via avoiding the mobilizations of

omentum and neighboring organs, obstructing their closing action on the

anastomotic sutures or even making leak by mechanically erosion of the

inosculation; and (4) is enclosed off rapidly [6]. Suction drainages can (1)

reduce the quantity of infection coming from exterior by preserving -ve pressure

on the tissue, (2) be accompanying with lesser post-operative adherences, (3) be

accompanying with lesser anastomotic leakages, and (4) be encapsulated less

rapidly. Suction drainages was utilized in 1 of the RCTs, while non-suction

drainages were utilized in the other [7].

We, consequently, performed a great, multi-center,

prospective, controlled by randomization, to find out (1) whether prophylactic

drainages reduced the complication severity and rate ultimately connected to

drainages, thereafter colonic resections followed directly by intraabdominal

suprapromontory colonic inosculation; and (2) whether one kind of drains

(suctions or non-suction) was better than the other.

83 cases with ages mean of 67 years (22-95) enrolled in this work

from (December 2020 to December 2021). Data collections of all cases was

completed but all the cases weren’t enrolled in the research at similar

time.

Sample size: As mean length of hospital stays due to

complications in drainage group 24.5+/-1.89 compared to 26.1+/-2.87 in

non-drainage group [2]. So, sample size is 74. Sample was increased 10% to avoid

follow up bias and to be 83. Sample has been estimated via Open Epi program with

95 % confidence and 80% power methods.

Colonic Preparations: All cases experienced colonic

mechanically preparations, counting the administrations of laxatives

(sennosides) or poly-ethylene glycol, that comprised the administrations of

enemas which were applied at 6 PM and in the morning (3 h) preoperatively. All

cases have a 1-dosage mixture of systemic ceftriaxone sodium and metronidazole

at anesthesia inductions.

Resections and Anastomosis: Mechanical bowel preparations has

been performed in all cases the day pre-operation. Colorectal inosculation

stapled by means of linear stapling device. AII colorectal inosculates were

performed by means of a circular stapling instrument and were intra-operatively

examined by trans-anal air insufflations. The intestine was unfocussed by a

defensive loop ileostomy in 38 cases of 53 cases who had pelvic drains and 12

cases out of 30 in no drainage group for rectal resection with whole mesorectal

excisions and coloanal inosculation in cases with lower rectal tumor.

Testing for Airtightness: The contributing physicians were

requested to examine for airtightness by observing bubbles appearance when the

colon barrier was swollen with air inserted into the colonic lumens, and digits

located on two sides of colorectal or colo- anal anastomoses, or by a

balloon-overstated Foley catheter introduced via the anus for distal colorectal

inosculates clamped proximally. If anastomotic leak was observed,

additional sutures were added till comprehensive airtightness was attained.

Random Allotment: After the resections and inosculation were

accomplished and confirmed for airtightness, cases experienced drainages (D+) or

not (D−), as shown below the creased upper right corner of questionnaires

rather than the envelopes technique. Cases have been located in D+. Arbitrary

allocation was stable via blocks of four in every center. This work was accepted

by the ethics committee of the coordination center.

Drainage: A locked drainage system of silastic has been utilized

in all patients, no suctions has been used. The diameter of drainage was 24 Ch.

End Points: The initially end point was the percent of cases

with 1 or more post- operative complications

ultimately connected to drainages, counting

(1) Deep complication that maybe impacted by drainages and for which drainages

can cause earlier diagnosing, counting anastomotic leakages, general or local

peritonitis, intraabdominal haemorrhage, or haematoma. Anastomotic leakages were

detected via the egress of fecal fluids via drain, by a following

procedure or an autopsy (accomplished regularly for all cases who passed away in

hospital). The post-operative interval comprised the total hospitalization,

regardless of its period, and the 30-day after discharging. All cases were seen

on that date as wounds surface (infections) or deep (hematomas, sores, and

fistulae) side-effects are recognized to happen after discharging.

Statistical analysis was performed via SPSS version20. Data had been examined for

normal distribution by means of the Shapiro Walk testing. Qualitative data have

been introduced as frequencies and relative percentages. χ2 test

was utilized to determine change among qualitative variables as specified.

Quantitative have been introduced as mean and SD. Student t testing has been

utilized to determine variance among quantitative variables in 2 groups.

Results considered significant at P-value < 0.05.

This study shows that a statistically significant change was found among the

study groups as (With drainage and Without drainage) regarding cardiovascular

dis, HTN, IHD, drain, open/Lap, covering stoma and mean mortality during

hospital stay.

A statistically nonsignificant change was found among the study groups as (With

drainage and Without drainage) regarding post op leak, localized, abscess,

generalised and mortality during hospital stay.

The current work showed that 3 out of 83 cases (2 with drains and one without the

drain) had a post anastomotic leak with significant difference in age,

cardiovascular comorbidities and no defunctioning stoma was done on the same set

with elective anterior resection [8,9].

Prophylactic drainage after elective Anterior resections with stapled colorectal

or colo-anal anastomosis decreases neither the rate of cases with one or more

post-operative complications maybe impacted by drainage nor the complications

severity.

This table (Table 1&2) shows that a statistically no significant change was

found among the study groups as (With drainage and Without drainage) and for

tumor site either Rectosigmoid or Rectal. No significant change was found

among the study groups as regard Neoadjuvant chemorad, Age, Gender, smoking, DM,

Steroids and ASA grade.

Table 1: Comparing among the study groups as regard

demographics.

|

|

With drainage

(n = 54)

|

Without drainage

(n = 29)

|

Test of Sig.

|

P

|

|

Rectosigmoid

|

4 (7.4%)

|

4 (13.8%)

|

χ2=0.883

|

FEp=0.441

|

|

Rectal

|

39 (72.2%)

|

19 (65.5%)

|

χ2=0.403

|

0.526

|

|

Neoadjuvant chemorad

|

3 (5.6%)

|

2 (6.9%)

|

χ2=0.060

|

FEp=1.000

|

|

Age

Mean ± SD.

Median (Min. – Max.)

|

66.30 ± 9.36

|

67.03 ± 12.53

|

t=0.304

|

0.762

|

|

66.30 ± 9.36

|

71.0 (28.0 - 84.0)

|

|

|

|

Gender

Male

Female

|

40 (74.1%)

|

17 (58.6%)

|

χ 2=2.094

|

0.148

|

|

14 (25.9%)

|

12 (41.4%)

|

|

Smoker

No

Smoker

EX

|

35 (64.8%)

|

26 (89.7%)

|

χ 2=6.058

|

MCp=0.04 4

|

|

4 (7.4%)

|

1 (3.4%)

|

|

15 (27.8%)

|

2 (6.9%)

|

|

DM

|

13 (24.1%)

|

5 (17.2%)

|

χ2=0.519

|

0.471

|

|

Steroids

|

2 (3.7%)

|

0 (0.0%)

|

0 (0.0%)

|

FEp=0.540

|

|

ASA

1

2

3

|

7 (13.0%)

|

5 (17.2%)

|

|

|

|

38 (70.4%)

|

18 (62.1%)

|

χ 2=0.601

|

0.741

|

|

9 (16.7%)

|

|

|

|

SD: Standard deviation, t: Student t-test, χ 2: Chi square

testing,

MC: Monte Carlo, FE: Fisher Exact,

*: Statistical significance at p

Table 2: Comparing among the study groups as regard different

parameters.

|

|

With drainage

(n = 54)

|

Without drainage

(n = 29)

|

Test of Sig.

|

P

|

|

Cardiovascular dis

|

2 (3.7%)

|

11 (37.9%)

|

χ 2=16.733*

|

FEp=<0.001

|

|

AF

|

0 (0.0%)

|

1 (3.4%)

|

χ 2=1.885

|

FEp=0.349

|

|

AO

|

0 (0.0%)

|

1 (3.4%)

|

χ 2=1.885

|

FEp=0.349

|

|

AVR

|

0 (0.0%)

|

1 (3.4%)

|

χ 2=1.885

|

FEp=0.349

|

|

Dil cardiomyopathy

|

0 (0.0%)

|

1 (3.4%)

|

χ 2=1.885

|

FEp=0.349

|

|

HF

|

0 (0.0%)

|

1 (3.4%)

|

χ 2=1.885

|

FEp=0.349

|

|

HTN

|

2 (3.7%)

|

6 (20.7%)

|

χ 2=6.250

|

FEp=0.019*

|

|

IHD

|

0 (0.0%)

|

3 (10.3%)

|

χ2=5.796*

|

FEp=0.040*

|

|

MVR

|

0 (0.0%)

|

1 (3.4%)

|

χ 2=1.885

|

FEp=0.349

|

|

Drain

|

54 (100.0%)

|

0 (0.0%)

|

χ 2=83.00

|

FEp =<0.001

|

|

Open/Lap

OPEN

|

37 (68.5%)

|

7 (24.1%)

|

χ 2=14.919

|

FEp<0.001

|

|

LAP

|

17 (31.5%)

|

22 (75.9%)

|

|

Covering stoma

|

42 (77.8%)

|

13 (44.8%)

|

χ 2= 9.164

|

FEp= 0.002

|

|

Post op leak

|

3 (5.6%)

|

1 (3.4%)

|

χ 2 =0.183

|

FEp =1.000

|

|

Localized

|

3 (5.6%)

|

0 (0.0%)

|

χ 2=1.672

|

FEp=0.548

|

|

Abscess

|

3 (5.6%)

|

0 (0.0%)

|

χ 2=1.672

|

FEp=0.548

|

|

Generalised

|

3 (5.6%)

|

0 (0.0%)

|

χ 2=1.672

|

FEp=0.548

|

|

Mortality during hospital

Stay

|

2 (3.7%)

|

0 (0.0%)

|

Χ2 =1.101

|

FEp=0.540

|

|

Mean ± SD.

|

10.25 ± 5.06

|

7.28 ± 2.90

|

|

|

|

Median (Min. – Max.)

|

9.0 (5.0 - 30.0)

|

6.0 (3.0 - 14.0)

|

Χ2 =418.50*

|

FEp=0.001

|

SD: Standard deviation; U: Mann Whitney test; χ 2: Chi square

testing;

FE: Fisher Exact

*: Statistical significance at p < 0.05

A statistically nonsignificant change was found among the study groups as

open/lap (With drainage and without drainage) post op leak, localized abscess,

generalized peritonitis and mortality during hospital stay.

Merad et al. [10] showed that the two studied groups were similar regarding pre-

operative data, excluding that there were significantly (P

value<0.02) more cases with ascites in cases who didn’t

experience drainages. In accordance with our findings, other parameters,

counting weight losing (P value<0.20), corticosteroids usage (P

value<.10), Crohn disorder (P value<0.30),

intra-operative fecal soiling (P<0.10), and leakages on testing for

airtightness (P value<0.50), were met more commonly in who

didn’t experience drainages, but these variances were nonsignificant

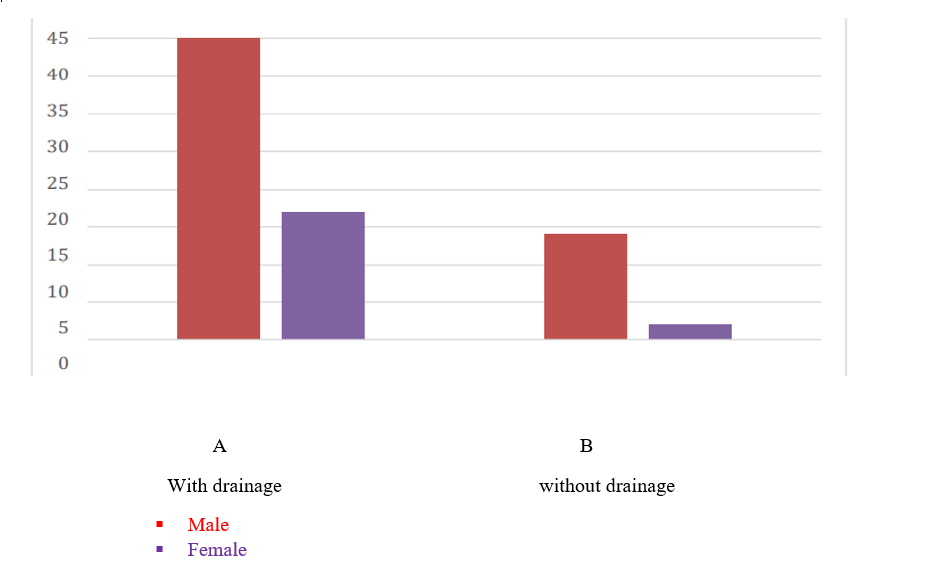

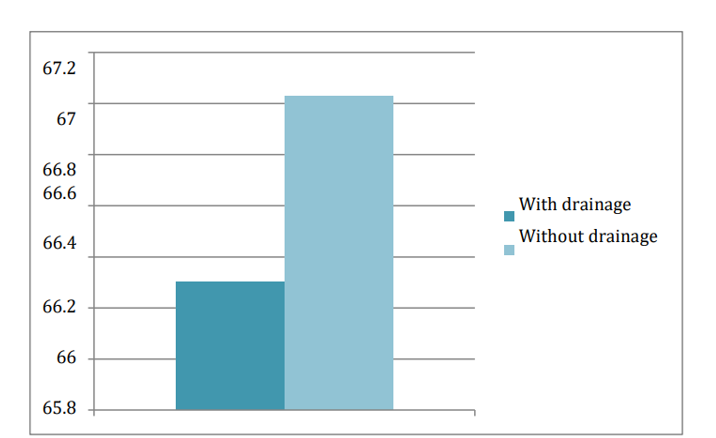

(Figure 1&2).

Figure 1: Comparing among the study groups (With drainage and

Without drainage) according to gender.

Comparing among the study groups as regard gender

Figure 2: Comparing among the study groups (With drainage and

Without drainage) according to age.

In agreement with our results, Hirahara et al. [2] found nonsignificant changes

in terms of the mean age of the cases, males/females’ ratio, BMI, and

concurrent disorders among the study groups.

In a systematic review by Podda et al. [11], several series stated a diversity of

risk- factors for AL post colo-rectal operation, counting age, pre-operative

nutritious condition, cardio-vascular and respirational co-morbidities,

incidence of opposing intra- operative effects, and the existence of a

de-functioning stoma. Tumor localizations in the lower and middle third of the

rectum, predominantly with an anastomotic height of<50 mm from the anal

border, have as well been measured clinical risk-factors for AL This study shows

that a statistically significant change was found among the study groups as

(With drainage and Without drainage) regarding cardiovascular dis, HTN, IHD,

drain, open/Lap, covering stoma and mean mortality during hospital stay. A

statistically nonsignificant change was found among the study groups as (With

drainage and Without drainage) and AF, AO, AVR, Dil cardiomyopathy, HF, MVR,

post op leak, localized, abscess, generalised and mortality during hospital

stay.

In disagreement with our results, Hirahara et al. [2] revealed that there

was insignificant difference between both groups as regard

cardiovascular diseases, Hypertension, Ischemic heart disease.

Post-operative outcomes are summarized in a study by Hirahara et al. [2]. Total

post- operative problems built on the Clavien-Dindo classifications were found

in 31% and 30% of cases in the drain and no drain groups, resp., and a

nonsignificant change was found in complication rates among the study groups.

There was no in-hospital death in this work, but single case in the no-drain

group who advanced Petersen’s hernia needed re-operation on

8thday post-operatively. As regard the post-operative

hospitalization, a nonsignificant change was detected among both groups. When

taking the existence and non-presence of post-operative problems into attention,

the hospitalization period didn’t vary among both groups.

In disagreement to preceding suggestion, the metanalysis by Rondelli et al., [12]

which enrolled randomized and nonrandomized reports, revealed that the existence

of a prophylactic drains decreased the occurrence of extra-peritoneal colorectal

AL and the rate of re-operations thereafter anterior rectal resection. But the

protecting value of PD was maintained by the data from nonrandomized reports

only, as the sub-group investigation of RCTs didn’t display any advantage

for PD usage.

Moreover, the big Dutch study by Peeters et al., [13] revealed that, on multi-

regression analysis, the non-presence of a pelvic drainages and a de-functioning

stoma were the issues accompanying with anastomotic dehiscence. More definitely,

the existence of one or more pelvic drains postoperatively was significantly

accompanied with a lower AL: 9.59% of cases with pelvic drainages had leakages,

in comparison with 23.50% of cases with no drain, and 8.20% of cases with a

de-functioning colostomy or ileostomy had a leakage, in comparison to 16% with

not a stoma. Consequently, the authors reported that, in a try to minimalize the

risks of clinical AL, the constructions of a de-functioning stoma and the

assignment of one or more drainages in the presacral cavity looks desirable for

cases with proximal as well as distal rectal tumors.

Merad et al. [10] showed that the post-operative death in their study was 4.4%,

which was within the rates of post-operative mortality reported in the other

studies:

3- 6% in a trial by Hoffmann et al. [14] and in a study by Sagar et al. [15]

Merad et al. [10] showed that 0.30% rate of mortality because of anastomotic

leakages was less than the rates of 0.85- 2.00% stated somewhere else in a study

by Hagmüller et al. [16] and a study by Sagar et al., [15]. In contrast,

there were no mortalities secondary to anastomotic leakages in 2 of the other

trials by Johnson et al. [17] and Sagar et al. [15].

Routine pelvic drainage after elective anterior resection does not reduce the

rate or severity of anastomotic leak. It may, infrequently, be harmful.

The Authors declares no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the

research, authorship, and / or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval and Consent to participate: Consent to

participate was gained by the patient.

Consent for publication: N/A

Availability of data and materials: All data and materials are

available if further steps required.

Competing interests: Not Applicable

Funding: There is no funding source -Authors' contributions:

Mr. Mena: collect the data, writing the article and do analysis; Mr. Bisheet:

review and revise the paper

- Abu-Omar Y, Kocher GJ, Bosco P, Barbero C, Waller D, et al. (2017) European

Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery expert consensus statement on the

prevention and management of mediastinitis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg

51: 10-29. [Crossref]

- Hirahara N, Matsubara T, Hayashi H, Takai K, Fujii Y, et al. (2015)

Significance of prophylactic intra-abdominal drain placement after

laparoscopic distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J Surg

Oncol 13: 181. [Crossref]

- Cerda-Cortaza JL, Prieto Aldape R, González Muñoz AH,

Campos-Campos SF, Fuentes Orozco C, et al. (2019) Results of a National

Survey on the preparation, management and monitoring of colonic anastomosis.

Cirujano General 41:168-176.

- Anderson TA, Anderson R, Nargozian C (2018) Specific Newborn and Infant

Procedures. Essentials of Anesthesia for Infants and Neonates, 199.

- Birolini C, de Miranda JS, Tanaka EY, Utiyama EM, Rasslan S, et al. (2020)

The use of synthetic mesh in contaminated and infected abdominal wall

repairs: challenging the dogma—a long-term prospective clinical

trial. Hernia 24: 307-323. [Crossref]

- Nussbaum MS, McFadden DW (2019) Gastric, duodenal, and small intestinal

fistulas. In Shackelford's Surgery of the Alimentary Tract, 2: 886-907.

- Watanabe Y, Koshiyama M, Seki K, Nakagawa M, Ikuta E, et al. (2019)

Development and themes of diagnostic and treatment procedures for secondary

leg lymphedema in patients with gynecologic cancers. In Healthcare,

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 7: 101.

- Saikaly E, Saad MK (2020) Anastomotic Leak in Colorectal Surgery: A

Comprehensive Review. Epidemiology 5: 6.

- Moro ML, Carrieri MP, Tozzi AE, Lana S, Greco D (1996) Risk factors for

surgical wound infection in clean surgery: a multicenter study.Ann Ital

Chir 67: 13–9. [Crossref]

- Merad F, Yahchouchi E, Hay J, Fingerhut A, Laborde Y, et al. (1998)

Prophylactic abdominal drainage after elective colonic resection and

suprapromontory anastomosis: A Multicenter Study Controlled by

Randomization. Arch Surg 133: 309–314. [Crossref]

- Podda M, Di Saverio S, Davies RJ, Atzeni J, Balestra F, et al. (2019)

Prophylactic intra-abdominal drainage following colorectal anastomoses. A

systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am

J Surg 219: 164-174. [Crossref]

- Rondelli F, Bugiantella W, Vedovati MC, Balzarotti R, Avenia N, et al.

(2014) To drain or not to drain extraperitoneal colorectal anastomosis? A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis 16:

O35-eO42. [Crossref]

- Peeters KC, Tollenaar RA, Marijnen CAM, Kranenbarg KE, Steup WH, et al.

(2005). Risk factors for anastomotic failure after total mesorectal excision

of rectal cancer. Br J Surg 92: 211-216. [Crossref]

- Hoffmann J, Shokouh-Amiri MH, Damm P, Jensen R (1987) A prospective

controlled study of prophylactic drainage after colonic anastomoses. Dis

Colon Rectum 30: 449- 452. [Crossref]

- Sagar PM, Couse N, Kerin M, May J, MacFie J (1993) Randomized trial of

drainage of colorectal anastomosis. Br J Surg 80: 769- 771. [Crossref]

- Hagmüller E, Lorenz D, Werthmann K, Trede M (1989) Prophylactic

drainage in elective colic resections? Program and abstracts of the

33rd World Congress of Surgery September 10-16.

- Johnson CD, Lamont PM, Orr N, Lennox M (1989) Is a drain necessary after

colonic anastomosis? J R Soc Med 82: 661- 664. [Crossref]