The authors report a case of Type I branchial fistula, a relatively rare lesion which requires a careful management from the diagnosis to the final surgical excision. In fact, the most frequent scenario implies one or more surgical drainages with recurrences before the proper diagnostic workout, based on an accurate examination and a RMN study. Surgical excision must take into account the risk of facial nerve injury and nowadays the standard of care recommends a magnification view and the facial nerve monitoring.

branchial anomalies, embryopathies, head and neck benign lesions

Branchial anomalies derive from an impaired maturation of the branchial apparatus, that consists of six pairs of arches, clefts and pouches and develops between the fourth and eight weeks of the embryogenesis.

This maturative disturbance may lead to the formation of branchial cysts (no communication, both with the skin, externally, and the pharyngeal mucosa, internally), branchial sinus (blind ending tubes which open to the skin) and branchial fistulas (open both to the skin and to the mucosa).

The incidence of such branchial abnormalityes accounts for the 17 % of all pediatric cervical masses [1].

Branchial cyst is the most frequent lesion and in the majority of the cases becomes evident between the first and third decade of life.

Among the branchial cleft anomalies, the second branchial cleft ones are the most frequent, followed by the first cleft, the third and the fourth.

First branchial cleft remnants are relatively infrequent. As of 2018, around 200 cases had been reported in the international literature [2].

Thus, it seemed to us worth reporting a recent observation of such a case, whose surgical excision always implies risks for the facial nerve and requires a careful pre-operative work up and a meticulous approach.

First branchial cleft anomalies (FBCAs) result from an incomplete fusion of the cleft between the first and second branchial arches. The first cleft and pouch form the external auditory canal (EAC), middle ear cavity, Eustachian tube and mastoid air cells [3].

The cutaneous (external) end of the sinus or fistula may be both into the EAC, the middle ear cleft, the post-auricular region and the neck near the angle of the mandible.

The accepted classifications are still the ones of Work (1972), [4] and Olsen (1980) [5].

In Work’s classification, Type I FBCAs are ectodermal and present as a cystic mass with squamous epithelium inside but without skin or cartilage. Type II FBCAs present as a cyst, sinus or fistula tract and are both ectodermal and mesodermal; they have squamous epithelium with skin or cartilage.

Olsen classified FBCAs into cysts (closed), sinuses (only external opening) or fistulas (both internal and external opening). This last classification is assumed to better point out the relationships with the facial nerve: fistulas are usually deep to the facial nerve, while cysts and sinuses are usually superficial to it [6].

Microtia is also described to accompany such anomalies and recently the first case of a FBCA associated with external auditory canal atresia and middle ear malformation has been described [7].

A 11-year-old boy, born in China and living in Italy, was referred to our institution complaining of a recurrent suppurative lesion in his right post-auricular region, with intermittent ear discharge. He had already undergone two surgical excisions at the county children hospital.

The first examiner (FM) found an inflamed and discharging ulcerative lesion. Under microscopic examination, purulent fluid was observed coming out from the EAC. Discharge increased when pressing onto the post-auricular lesion. A wide spectrum antibiotic therapy was prescribed, together with ear irrigations and medication of the ulcer. The patient was further examined after two weeks by the senior author (SD): the post-auricular lesion had decreased in volume and appeared dry and obliterated by a crust (Figure 1). At palpation it had an ovoid shape, with 2 cm diameter and appeared to go deeply in an inferior-posterior to superior-anterior direction under the conchal cartilage. Under otomicroscopic and otoendoscopic examination, no more secretion was found. EAC skin and tympanic membrane (TM) appeared healthy and normal. No orifice was found on the whole EAC walls. The crusts were removed from the post-auricular lesion and the residual granulation tissue was soaked with methylene blue. No blue liquid was observed into the EAC, neither after massage of the post-auricular lesion.

Figure 1: Right post-auricular ulcerated lesion.

Taking into account the possibility of a branchial lesion, also in consideration of the two previous incomplete excisions, a magnetic resonance study (MRI), with contrast medium, was suggested and the child’s father was thoroughly informed about the possible embryologic origin and the need to deepen the diagnosis.

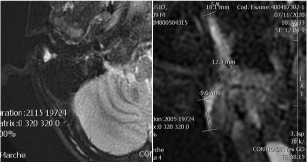

MRI imaging (Figure 2,3) showed a subcutaneous right post-auricular focal lesion, expandable, small (maximum axial diameter 20 mm) and elongated (cranio-caudal diameter 40 mm). The margins were not completely sharp and surrounding edema and hyperemia were present. Internal signal intensity was not homogeneous for the coexistence of small liquid components and spots of restricted diffusion. Reactive nodes were visible nearby in the parotid region. Facial nerve was not found in adjacence of the lesion.

Figure 2: Axial T1 post contrast (left). Axial Diffusion imaging (right).

Figure 3: Axial (left) and coronal enlarged (right) STIR imaging.

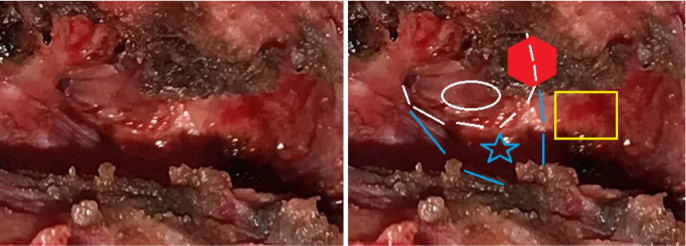

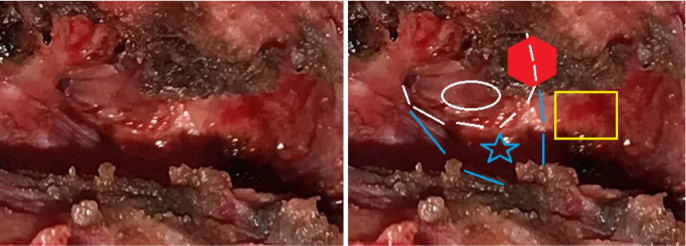

A surgical excision was planned and an informed consent obtained. The child’s facial nerve was monitored and the operation carried out under loupe magnification. A surgical incision around the whole pathologic post-auricular skin was accomplished and a careful subcutaneous dissection was performed. A thick fistulous tract was identified (Figure 4) and followed deeply and posterior-superiorly until its end, that was ascertained to be against the most medial and inferior part of the posterior bony wall of the EAC. In other words, at the inferior junction of the tympanic bone with the mastoid bone (Figure 5). During the dissection, the soft tissues were carefully checked for facial nerve neural response, but the nerve was not encountered. When the deep (internal) end was detached from the bone, it opened and epithelial (“cholesteatoma-like”) debris were found occupying most of the deep end itself. The excision appeared radical. Nevertheless, a cautious bipolar coagulation of the place of insertion was performed. The cutaneous EAC appeared closed and no water leakage was noted when filling the EAC with saline plus antibiotic.

Figure 4: The fistulous tract becomes ticker as it goes deep.

Figure 5: View after the excision. Blue lines and star: bony posterior wall of the EAC. White lines an ellipse: cutaneous posterior wall of the EAC. Yellow rectangle: mastoid bone. Red hexagon: coagulated end of the fistula.

After several irrigations with saline and antibiotic solution, the surgical wound was packed with iodoform gauze and only partially closed. Post-operative course was uneventful. The gauze was progressively removed after two days (on patient’s hospital discharge), and then on post-operative days four and six. The wound was sutured at the eighth post-operative day. After three month the healing process was complete and no more problem was present.

Pathologic examination

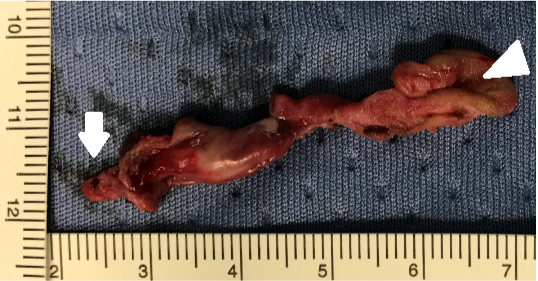

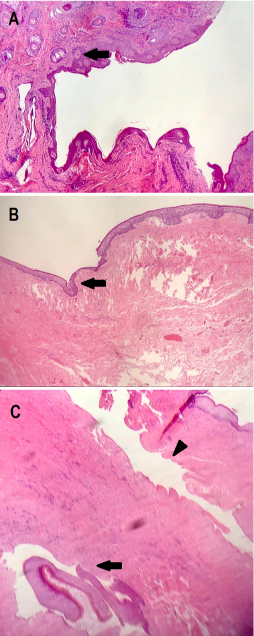

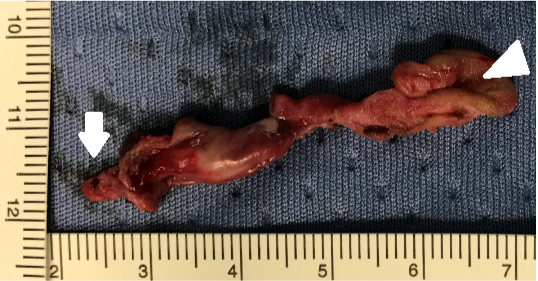

The fistula was excised in monobloc and was about 5 cm long with a 2-3 mm wide lumen (Figure 6). Pathologic examination confirmed the presence of the sole squamous lining and the absence of skin adnexa (Figure 7).

Figure 6: Fistula with cutaneous orifice (white triangle) and deep end (white arrow).

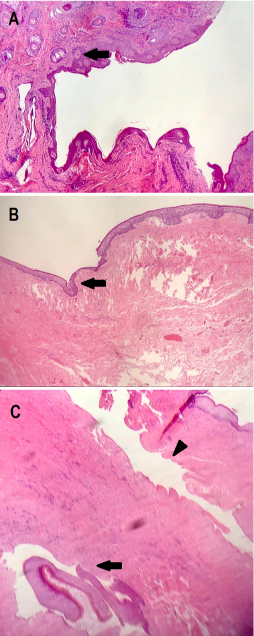

Figure 7:

A: Cutaneous orifice, identified by the presence of sebaceous glands (arrow).

B: Fistulous tract. No skin lining but only squamous epithelium, with a thick lamina propria (arrow). No skin adnexa are present.

C: Fistulous tract longitudinal view (arrowhead) and tangential section (arrow). It appears as a long-lasting lesion, with scarce surrounding inflammation and significant fibrous reaction.

FBCAs still represent an infrequent finding and the “general otolaryngologist”, especially the one working in a primary and also a secondary care setting, must keep it in clear mind. In fact, there are both a problem of right diagnosis and the necessity of a resolutive therapy.

Children but also young adults presenting with an intermittent, suppurative and ulcerated mass or lesion that is placed behind or inferior to the ear lobe, must be suspected as having a branchial anomaly and must be addressed with a complete workout. The case we hereby present had been previously seen at a children’s hospital and undergone two surgical drainages. Diagnostic workout must include an accurate clinical examination, with microscopic and/or endoscopic view of the external ear canal (EAC) and tympanic membrane (TM), in order to find out any opening of the supposed fistula. Injecting methylene blue into the ulcerative post-auricular lesion may be useful. In our case, however, while at the first visit fluid was recognized to come out from the EAC, an accurate otomicroscopic and otoendoscopic further observation, after methylene blue injection, failed to see any communication, and also the intraoperative examination did not show any violation of the cutaneous posterior wall of the EAC. When trying to classify this our own case, the absence of skin lining the lumen is congruous with a Type I FBCA, according to Work’s classification, even though it was not a cystic mass but a tubular lesion. In regards to this last feature, the deep (proximal) end impacted onto the tympanic bone and no communication with the EAC was found. According to Olsen’s classification, this could be considered both with a blind (cul de sac) ending (sinus), and with an open orifice adherent to the bone, thus being named as fistula. The fact that the facial nerve was not found in contiguity with the lesion and could be supposed to be deep to it, seems to corroborate the hypothesis that our patient had a sinus-type FBCA. Whatever the type of FBCA, pre-operative imaging is mandatory and RMN is currently the gold standard [8]. Imaging helps to confirm the diagnostic suspect, may be useful to distinguish between type I or type II FBCA and must be addressed to study the relationships between the lesion and the facial nerve. From the treatment standpoint, radical surgery is the sole resolutive choice. Surgical planning must always expect a difficult excision, with the presence of a sinus and/or a fistula, even though clinical examination and imaging are uncertain. Accurate pre-operative counselling as well as facial nerve monitoring are at present mandatory, and magnification view is strongly recommended. In our opinion the patient should be operated after a previous accurate medical preparation so that the inflammation has been reduced to a minimum. Intraoperative methylene blue injection can be both useful and confusing. We would suggest not to use it until finding and following the fistula/sinus or the mass is achievable.

In regards to the pinna and the EAC, differently from what suggested by Liu and Co. (2017) [9], we prefer, whenever possible, to avoid any cartilaginous incision, to prevent the risk of EAC stenosis. On the other end, an accurate and complete removal of the proximal (auricular) end of the lesion is mandatory in order to avoid a deep recurrence that would make the reintervention mostly risky. In our opinion, when such cases are correctly suspected and studied, their surgically excision paradoxically results not so difficult and might not require a referral to a children hospital or to a tertiary care institution.

Stefano Dallari: clinical workup, surgery, data collection, manuscript preparation and revision.

Federica Maroni: clinical workup, data collection

Alessandra Filosa: pathologic examination, manuscript revision

Massimo Giuliano Bonetti: imaging revision, choice of radiologic images, manuscript revision

The Authors deny any financial and non-financial interests, affiliations or any personal, racial and intellectual properties.

- Spinelli C, Rossi L, Strambi S, Piscioneri J, Natale G, et al. (2016) Branchial cleft and pouch anomalies in childhood: a report of 50 surgical cases. J Endocrinol Invest 39: 529–535. [Crossref]

- Bagchi A, Hira P, Mittal K, Priyamvara A, Dey AK (2018) Branchial cleft cysts: a pictorial review. Pol J Radiol 83: e204-e209. [Crossref]

- Kumar R, Sikka K, Sagar P, Kakkar A, Thakar A (2013) First branchial cleft anomalies: avoiding the misdiagnosis. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 65: 260–263. [Crossref]

- Work WP (1972) Newer concepts of first branchial cleft defects. Laryngoscope 82: 1581–1593. [Crossref]

- Olsen KD, Maragos NE, Weiland LH (1980) First branchial cleft anomalies. Laryngoscope 90: 423–436. [Crossref]

- Magdy EA, Ashram YA (2013) First branchial cleft anomalies: presentation, variability and safe surgical management. Eur Arch. Otorhinolaryngol 270: 1917–1925. [Crossref]

- Zhang CL, Li CL, Chen HQ, Sun Q, Liu ZH (2020) First branchial cleft cyst accompanied by external auditory canal atresia and middle ear malformation: A case report. World J Clin Cases 8: 3616-3620. [Crossref]

- Adams A, Mankad K, Offiah C, Childs L (2016) Branchial cleft anomalies: a pictorial review of embryological development and spectrum of imaging findings. Insights Imaging 7: 69–76. [Crossref]

- Liu W, Chen M, Hao J, Yang Y, Zhang J, et al. (2017) The treatment for the first branchial cleft anomalies in children. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 274: 3465–3470. [Crossref]